The best of the year in “show, don’t tell”

A Time for Greatness, Courage, and Moderation

Our dark hour calls for a recovery of the statesman’s virtues.

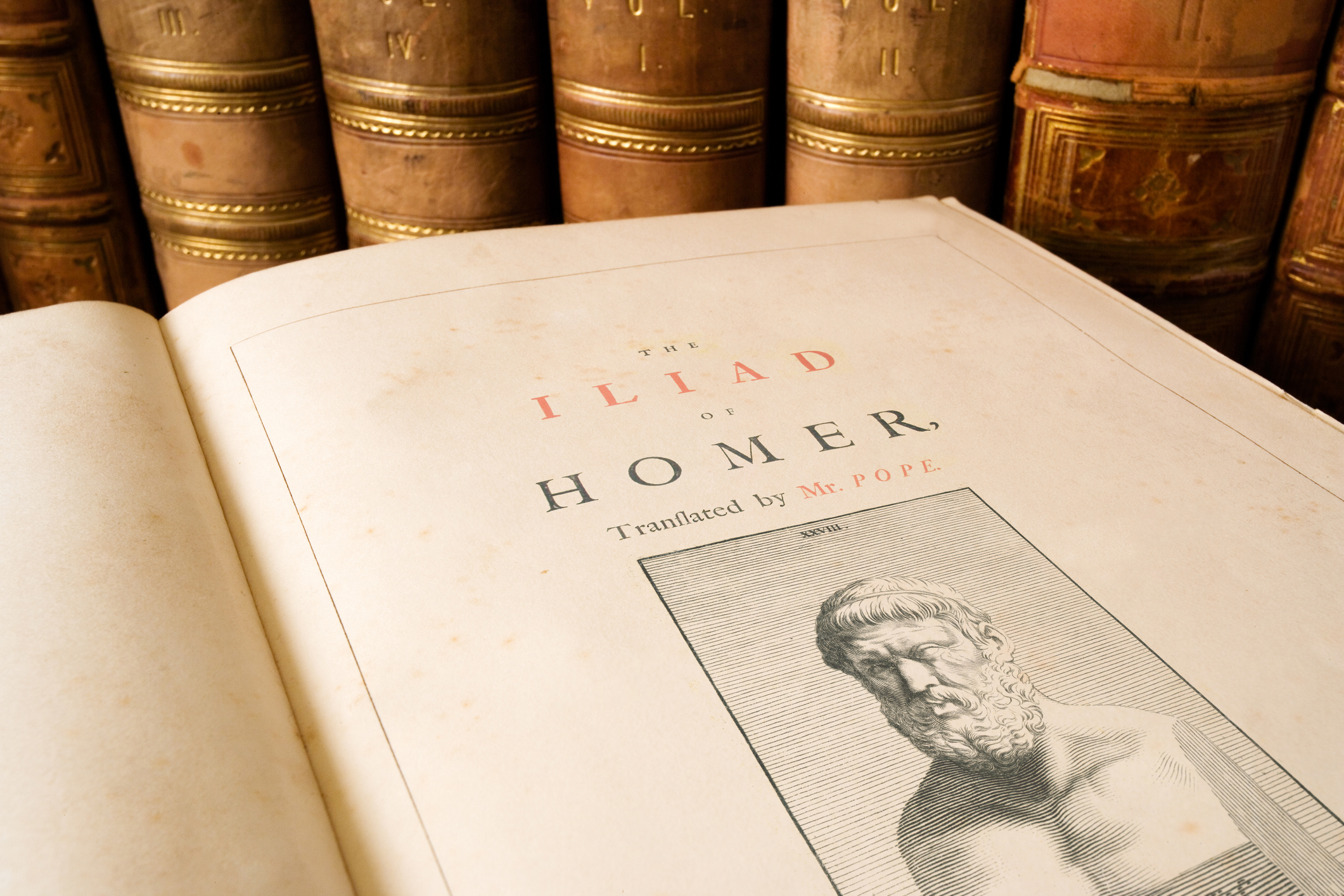

The following remarks were originally presented as an acceptance speech for the Intercollegiate Studies Institute’s Conservative Book of the Year award, which the author received for his book The Statesman as Thinker: Portraits of Greatness, Courage, and Moderation.

The inheritance we defend—that noble civilizational patrimony that helps define the West and America—is not good simply because it is old or because it is ours. But it is wisdom tried and true. As a result, we know that we can never begin anew with some revolutionary “Year Zero.” The destructive zealots and ideologues among the French Revolutionaries did that, displaying deadly contempt for Burke’s more capacious understanding of a primordial contract that connects the living, the dead, and those yet to be born. As a tradition dedicated to human liberty, the Western tradition is dynamic and expansive, yet it has ample room for true pietas. As the French political philosopher Bertrand de Jouvenel wrote so eloquently in his 1955 classic, Sovereignty: An Inquiry Into the Political Good: “[E]very individual with a spark of imagination feels deeply indebted to many others, the living and the dead, the known and the unknown…. The wise man knows himself for debtor, and his actions will be inspired by a deep sense of obligation.”

Reason and experience alike testify that men and women become monsters when they confuse themselves with gods beholden to nothing or no one. In our times that conceit has led to utopian dreams and murderous rage, or to petty souls who rest content with what Blaise Pascal vividly called “licking the earth.” Real human freedom and dignity need to be nourished by a deep sense of obligation, starting with our forebears, without whom we would not be or have anything at all. Natural piety, however, is not solely focused on the past: it lifts our gaze further outside ourselves to the mysterious givenness of the natural order. It is open to the grace that lifts our spirits and allows us to experience the presence of the Living God. Only by acknowledging our considerable debts to our forebears, to ennobling tradition, and to the natural and divine sources of our dignity as human beings, are we rendered capable of achieving great and good things in our turn.

The last phrase, “great and good,” leads me to the book for which I am being honored: The Statesman as Thinker: Portraits of Greatness, Courage, and Moderation. In it I argue that the twin virtues of magnanimity and moderation—greatness of soul and a deeply-felt sense of obligation to truth, liberty, and conscience—go hand in hand. In the domain of action, what towers above and truly endures is the admittedly rare combination of honorable ambition and self-conscious self-limitation, where greatness and goodness coexist in (relative) harmony, if in some tension.

Washington was one such exemplar of noble, honorable, and morally serious ambition, which he yoked to the service of his fledgling country and the larger cause of civilized liberty. Across the Atlantic, Napoleon famously complained that his contemporaries wanted him to be another Washington: a great man willing to leave the stage and to go home when his duty was done. This he could not do. Tocqueville said of Napoleon that he was as great as one could be without being good. That “without being good” was his Achilles’ heel, his fatal flaw. Closer to our day, Charles de Gaulle said that Napoleon severed greatness and moderation, a lesson that should be instructive for future generations. Writing in 1924, de Gaulle observed that the great man’s “works of energy” fizzle out, or give rise to tragedy, when they are severed from “the rules of classical order.” From an appreciation of “the limits marked out by human experience, common sense, and the law,” truly magnanimous statesmanship learns “the sense of balance, of what is possible, of measure, which alone renders the works of energy durable and fecund.”

De Gaulle already saw this severing of greatness and measure at work in the Nietzscheanized military and political elites of Wilhelmine Germany. How much worse, however, was the contempt for decency, moderation, and the moral law that informed Hitler’s monstrous “revolution of nihilism”! Communism, too, warred unrelentingly against all the human goods, all the precious achievements of civilization: against truth, against human liberty and dignity, against the very idea of natural right, and against the “enduring verities” that transcend class interests and revolutionary pretensions. The Nazi and Communist efforts to impose what Eric Voegelin memorably called mendacious “Second Realities” on the only human condition we know, gave rise to forms of murderous tyranny hitherto unimaginable. We conservatives are uniquely equipped to recognize the essential unity between these two totalitarian regimes. How sad—but how instructive—that “progressives” everywhere, and far too many among the young, still believe that Communism is “good in theory” and desirable in practice.

As a country and as a civilization, we have failed miserably in passing on the lessons of the 20th century to new generations. Chief among those lessons was a great warning against ideological Manicheaism, which locates evil not in the flawed human heart, but in suspect groups (e.g., the Jews, the kulaks, religious believers, the bourgeoisie, assorted class enemies). This is an invitation, indeed, a sure route, to Hell on earth.

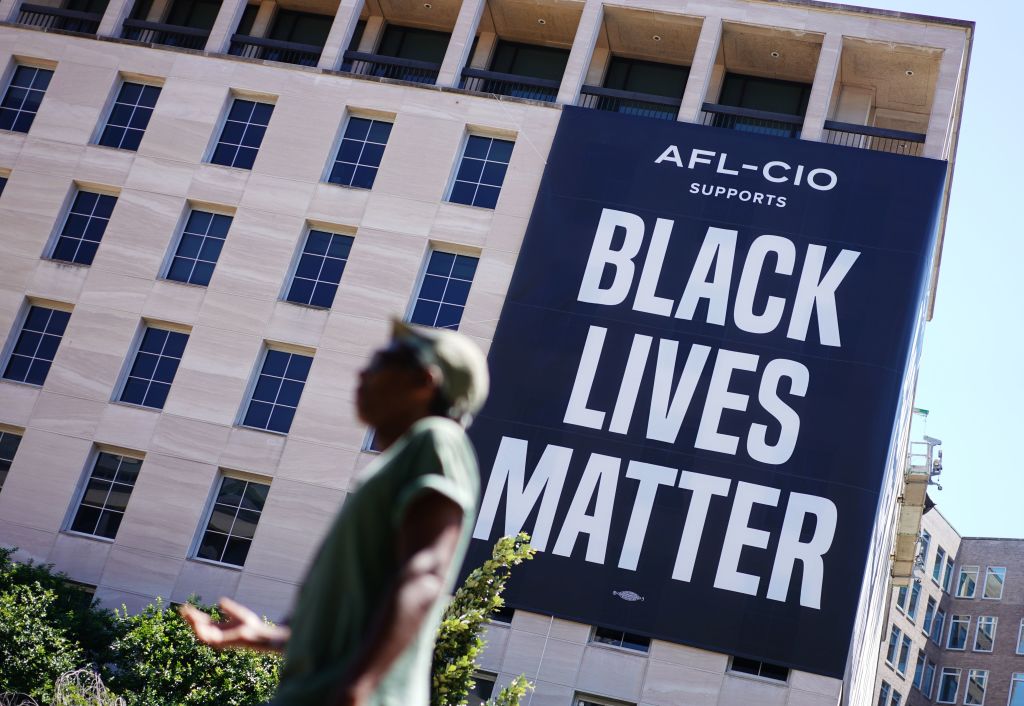

The New Totalitarians

Today, nearly 35 years after the annus mirabilis of 1989, we are observing a repetition in new form of the ideological Lie. Progressives willfully see in imperfect but largely decent societies nothing but evil, injustice, and exploitation. Critical Race Theory and “wokeness” have replaced gratitude to our forebears and democratic self-respect, and new groups of people, alleged oppressors, are called to loathe themselves or to be banished from the civic and human community. Such unrelieved contempt for our fellow citizens has nothing to do with justice, social or otherwise. Quite the contrary. It makes a mockery of the shared bonds that make free civic life possible, and it creates a fictive world of permanent victims and oppressors. And it is light years away from the affirmation of common humanity.

So much for the moral realism that affirms, in Solzhenitsyn’s famous words from The Gulag Archipelago, “that the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either—but right through every human heart—and through all human hearts.” Faced with human nature in extremis in the Soviet Gulag, Solzhenitsyn rediscovered a truth central to classical and Biblical wisdom, as well as to the sober moral and political wisdom of our founding fathers: “It is impossible to expel evil from the world in its entirety, but it is possible to constrict it within each person.” To acknowledge this is to begin to find wisdom and self-knowledge.

In contrast, the woke—coercive moral and political fanatics to the core—renew the ideological Lie in the name of fighting racial, ethnic, and sexual injustice. But they end up tyrannizing the soul, polluting the public space with insidious clichés, because they do not begin to understand the moral drama that animates each and every human soul. They only know how to negate and repudiate, to destroy the precious and fragile inheritance that has been passed on to us for our safekeeping. To meet this threat, we need new statesmen to arise—to be cultivated—among us. Pending that, each of us needs to have some “tincture” of the statesman in him or her.

People often ask me how we can renew the noble tradition of statesmanship represented by Solon and Cicero in antiquity, and by the likes of Burke, Washington, Lincoln, Churchill, de Gaulle, and Havel, closer to home. The first thing to do, of course, is to study them. As it happens, that is what they themselves did. Cicero’s On Duties is a truly estimable work that shaped the moral and political imagination of the West until the late 19th century. As I describe in my book, his honorable statesman is equally distant from the Machiavellian Prince and the Nietzschean “Overman,” contemptuous as they are of traditional moral wisdom and an ethic of self-restraint and honorable ambition. But neither is Cicero’s statesman averse to the legitimate, tough-minded exercise of authority that repels contemporary humanitarians. Neither hard nor soft in his moral bearing, the true statesman takes his bearing from the “honestum”—the fine, the noble, the honorable—at the service of civilized liberty. Liberty’s moral preconditions and purposes are the statesman’s lodestars.

This is the realistic yet high-minded framework of thought and action that our theorists of repudiation so mindlessly aim to bury. Instead of legitimate authority, instead of decent norms that serve a community of citizens, they see only implacable power: crude, oppressive, self-serving, and now, predictably, “racist” to the core. These secular priests see only domination where others rightly discern love, consent, community, and the bonds of affection, civic and familial. “The heresy of domination,” as Roger Scruton calls it, takes a partial truth—that authority can become authoritarian and domineering—and turns it into a fanatical obfuscation, a refusal “to accept that power is sometimes benign and decent, like the power of a loving parent, conferred upon the object of love.” The partisans of this heresy govern those social and cultural institutions they have come to commandeer, like the universities and the media, in the very manner they condemn.

As I argue in the closing pages of my book, “our task is to reaffirm the real in a spirit of gratitude for what has been passed on by our forebears as a precious gift.” Only by “repudiating repudiation” do we have a fighting a chance of again seeing the likes of the great statesman-thinkers I describe in my book. But that act of moral recovery and civilizational renewal will demand an exercise of grandeur and moderation that will test our mettle as free and civilized men and women. True moderation will demand rare courage, not tepid passivity before the forces of self-loathing, negation, and repudiation. That is the “false, reptile courage” that Edmund Burke saw at work among English Whigs who wanted to make their peace with Jacobinism. To cite the last sentence of my book, “the choice is ours.” There is no reason to despair, because free will is a gift from on High. It is up to us to exercise it prudently, justly, and courageously—that is, wisely.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

We have no choice but to build anew.

The World Cup revealed wokeism’s Achilles’ heel.

You can’t change the people around you, but you can change the people around you.

Rising wokeness in medical schools is a problem for patients everywhere.

Woke commissars cannot be allowed to terrorize employees.