A look at the data

A Storm for Which We Were Unprepared

Senator Bill Frist saw it coming years ago.

Senator William Frist, M.D. is a nationally acclaimed heart and lung transplant surgeon and the former Majority Leader of the U.S. Senate. In 2005, during his tenure in Congress, he delivered the Marshall J. Seidman Lecture for the Department of Health Care Policy at Harvard University. In this strikingly prescient speech, he foretells the possibility of a viciously deadly pandemic and calls for action to defend against that eventuality on a vast scale. Though his warnings went unheeded, we are honored to publish his words now as part of our ongoing efforts to understand and counteract COVID-19 and its effects.

I am a physician and a surgeon who by accident of fate finds himself in the halls of power at a time of dangers for his country and the world, the most compelling of which are exactly those a physician is trained to recognize and fight. To me it seems no more natural to be a United States senator, and in my case the majority leader of the Senate, than it did to Harry Truman, who spent so many hard and unambitious years as a farmer and then found himself in such a place and at such a time as he did. And, like him, as someone who comes from the outside, and for whom the perquisites of power appear strange and irrelevant, I have asked myself what my purpose is as a public servant, what my obligations are, and what high precedents I should follow.

After some thought, I have determined my purpose, I know my duty and obligations, the precedents to honor, and why—neither history nor life itself being empty of example. Just as a surgeon must follow a purely objective course and a general must look at war with a cold and steady eye, a statesman must operate as if the world were free of emotion. And yet, to rise properly to the occasion, the surgeon must have the deepest compassion for his patient, the general must have the heart of an infantryman, and the statesman must know at every moment that the cost of his decisions is borne, often painfully, by the sovereign population he serves—all as if the world were nothing but emotion. The difficulty in this is what Churchill called the “continual stress of soul,” the rack upon which the adherents of these professions, if they meet their obligations well, will of necessity be broken.

In balancing objectivity with emotion, the practical with the moral, the smooth operation of power with its homely and human effects, one is driven to consider first things and elemental purposes, and this consideration makes clear that the guiding star of statesmanship is not aggrandizement of the state or the furtherance of a philosophy or ideology, and neither glory nor ambition nor accumulation of territory or riches. Rather, the guiding star must be the fact of human mortality, and the first purpose of a public official a simple watch upon the walls. We are charged above all with assuring the survival of the nation and protecting the lives of those whom we serve and who have put us in our place, entrusting us with this gravest of responsibilities.

Whether leading a small nomadic band, captaining a ship, or at the head of a huge industrial nation, the task is the same. It is not merely that which can be accomplished with sword and shield, but, rather, the exercise of courage, sacrifice, and judgement, in the preservation of the life of a nation in its people as families and individuals. And as if by design, this task becomes in its execution a principle that unites the powerless and powerful in an unimpeachable equality.

Clear and Present Danger

In times of peace and prosperity, whole nations sometimes willfully forget that we are mortal, and the forgetfulness then can rule beyond its natural life even in the face of war and pestilence, when by all accounts the star of mortality shines in air cleared of the luminous distractions of peace.

Like everyone else, politicians tend to look away from danger, to hope for the best, and pray that disaster will not arrive on their watch even as they sleep through it. This is so much a part of human nature that it often goes unchallenged. But we will not be able to sleep through what is likely coming soon—a front of unchecked and virulent epidemics, the potential of which should rise above your every other concern. For what the world now faces it has not seen even in the most harrowing episodes of the Middle Ages or the great wars of the last century. And not only are we unprepared for rampant epidemics, we have not taken sufficient note of the fact that though individually each might be devastating, they are susceptible of either purposeful or accidental combination, in which case they could be devastating almost beyond imagination.

The history of pathogens advances in parallel with and is no more static than our own, with which it is always intertwined, even if at times invisibly. Sometimes it rushes forward with great speed and breathtaking evolutionary vigor, and sometimes it rests in slow backwaters. When, in 1967, the U.S. Surgeon General declared that we had won the war on infectious diseases, we thought the slack water would last forever. But that war had never ended other than in wishful thinking.

Even now we accept as normal, because it is normal, that more than a quarter of all deaths—fifteen million each year—are due to infectious diseases. Three million children die every year of malaria and diarrheal diseases alone, one child every ten seconds. As sobering as this may be, we have been nonetheless in a quiescent stage of the mutability of pathogens, a hiatus from which they are now poised to break out. When viral diseases evolve normally—such as in the typical course of the human influenza virus undergoing small changes in its antigenicity and killing an average of 500,000 people annually throughout the world—it is called an antigenic drift. When they emerge with the immense power derivative of a jump from animal to human hosts followed by mutation and/or recombination with a human virus, as in the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919, in which 500 million people were infected and 50 million died, including half a million in the United States, it is called an antigenic shift.

To have believed with the Surgeon General forty years ago that the great advances of biological science were capable of permanently suppressing infectious disease was to have been unaware that these triumphs were appropriate only to one phase in the life of a continually evolving enemy whose natural rate of evolution and adaptation is far greater than our own. Shifts are the result of random, fortuitous, and unavoidable changes. Human population increase, concentration, and spread, intensification of animal husbandry, and greater wealth in developing countries bring animals both wild and domestic into closer contact with ever-larger numbers of people. War, economic catastrophe, and natural disasters subdue active measures of public health. The unprecedented use of antibiotics builds unprecedented resistance. Travel, trade, and climate change bring into contact disparate types and strains of disease. And as a consequence of all this, microbes evolve, mutate, and find new lives in new hosts.

The annual toll of infectious diseases worldwide—including four million from respiratory infections, three million from HIV/AIDS, and two million from waterborne diseases such as cholera—is a continuing and intolerable holocaust that, while sparing no class, strikes hardest at the weak, the impoverished, and the young. But this is just a beginning, in that the evidence strongly suggests that we are at the threshold of a major shift in the antigenicity of not merely one but several categories of pathogens, for never have we observed among them such variety, richness, opportunities for combination, and alacrity to combine and mutate. HIV, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (mad cow), avian influenzas such as H5N1, and SARS are merely the advance patrols of a great army forming out of sight, the lightning that however silent and distant gives rise to the dread of an approaching storm—a storm for which we are entirely unprepared. How can that be? How can the richest country in the world, with its great institutions, experts, and learned commissions, have failed to make adequate preparation—when preparation is all—for epidemics with the potential of killing off large segments of its population?

Precedent and Presage

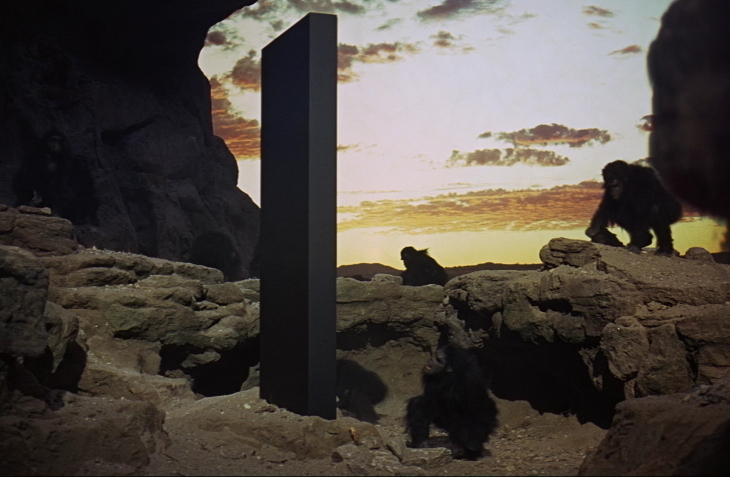

To see what lies on the horizon one need only look to the relatively recent past. I have a photograph of an emergency hospital in Kansas during the 1918 influenza pandemic. People lie miserably on cots in an enormous barn-like room with beams of sunlight streaming through high windows. It seems more crowded than the main floor of Grand Central Station at five o’clock on a weekday. In this one room several hundred people are in the throes of distress. Think of 2,000 such rooms filled with a crush of men, women, and children—500,000 in all—and imagine that the shafts of sunlight that illuminate them for us almost a century later are the last light they will ever see. Then bury them. That is what happened.

How would a nation so greatly moved and touched by the 3,000 dead of September 11th react to half a million dead? In 1918-1919 the mortality rate was only 10%, which seems merciful in comparison to the near 100% rate common to hemorrhagic fevers. Nor is influenza nearly as infectious as, for example, smallpox. How, then, would a nation greatly moved and touched by 3,000 dead, react to five or fifty million dead?

Smallpox is just one of many threats. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union, which stockpiled 5,000 tons annually of biowarfare-engineered anthrax resistant to 16 antibiotics, also produced massive amounts of weaponized smallpox virus just as universal immunization had come to a halt. As a result of conditions prevalent during the dissolution of the USSR, it is impossible to rule out that quantities of this or other deliberately manufactured pathogens such as anthrax, pneumonic plague, tularemia, etc. may find or may have found their ways into the possession of terrorists such as bin Laden and al-Zarqawi. Although the United States has put up enough—questionable—smallpox vaccine for the entire population, it has neither the means of distribution nor the immunized personnel to administer it in a generalized outbreak, nor the certainty that the vaccine would be relevant to a specific weaponized strain of the virus. Ring vaccination would be useless if the pathogen were released at many sites simultaneously, and in such a circumstance hospitals and the now nonexistent auxiliary means of relief would be quickly overwhelmed.

Panic, suffering, and the spread of the disease would intensify as—because people were dead, sick, or afraid—the economy ceased to function, electrical power flickered out, and food and medical supplies failed to move. Over months or perhaps years, scores of millions might perish, with whole families dying in their houses and no one to memorialize them or remove their corpses. Almost without doubt, the epidemic would spread to the rest of the world, for in biological warfare an attack upon one country is an attack upon all. Every vestige of modernity would be overturned. The continual and illusory flirtation with immortality that is a hallmark of scientific civilization would shatter, and we would find ourselves looking back upon even the most difficult times of the last century as a golden age. Despite the common wisdom, humanity has not moved beyond this kind of scenario. Of late it has moved unnecessarily and gratuitously toward it.

Any number of unknown viruses for which at present there is neither immunization nor cure are at this moment cooking in Asia and Africa, where they arise in hotbeds of densely intermingled human and animal populations. We are in unexplored territory. Economic and environmental changes in Asia have forced wilderness-deprived waterfowl to alight to feed amid farm animals in newly dense populations due to recently acquired wealth and dietary expectations, in a culture in which live poultry is brought to market. The reassortment of viral DNA as a result of this mingling is so frenzied that it is only a matter of time until the emergence of a virus unequaled in transmissibility and virulence. The epidemiological calculus of flu is notoriously volatile due to the unknowns of rapid reassortment. We do know now, however, that the incidence of H5N1 has been underestimated, that North Korea may be at the cusp of an Avian Flu crisis, and that we are woefully underprepared even for a virus that we can foresee, much less for one that we cannot.

No such viruses have yet reached critical mass or leapt from the channels imposed by their inherent limitations, environmental obstacles, and deliberate actions to contain them. But the evidence I have seen, the patterns of history, and new facts such as rapid, voluminous, and essential travel and trade; the decline of staffed hospital beds; and a now heavily urbanized and suburbanized American population dependent as never before upon easily disrupted networks of services and supply, lead me to believe that—especially because vaccines, if they could be devised, would not be available en masse until six to nine months after the outbreak of a pandemic—the imminence of such viruses might result in the immensely high death tolls to which I have alluded.

It is true that none of these viruses has yet spread geometrically—instantly and irrevocably overcoming health care systems and pulling us backward across thresholds of darkness that we long have believed we would never cross again. And yet this they might do—either entirely on their own or as a result of intentional human intervention. No intelligence agency, no matter how obsessively and repeatedly rearranged, and no military, no matter how powerful and dedicated, can assure that a few technicians of middling skill using a few thousand dollars’ worth of readily available equipment in a small and apparently innocuous setting cannot mount a first-order biological attack. It is possible, for example, to unite the prairie-fire infectiousness of smallpox with the almost absolute fatality of Ebola fever. It is possible simply and inexpensively to synthesize virulent pathogens from scratch, or to engineer and manufacture prions that, introduced undetectedly over time into a nation’s food supply, would after a long delay afflict virtually the entire population with a terrible and uniformly fatal disease. Unfortunately, the permutations are so various that the research establishment as now constituted cannot set up lines of investigation to anticipate even a small proportion of them. Never have we had to fight such a battle, to protect so many people against so many threats that are so silent and so lethal.

But is it reasonable to assume that anyone might resort to biological warfare? Indeed it is. Al-Qaida has declared that, “We have the right to kill four million Americans—two million of them children…[and] it is our right to fight them with chemical and biological weapons.” In Al-Istiqlal, the weekly of Islamic Jihad, we read that “it is the duty of Muslims to act in any possible way to acquire weapons of mass destruction, starting with nuclear weapons and ending with chemical and biological weapons.” It is hardly necessary, however, to rely upon stated intent. One need only weigh the logic of terrorism, its evolution, its absolutist convictions, and the evidence in documents and materials found in terrorist redoubts.

Those who equate terrorism with its targets and take false comfort in attributing to the terrorist the moral status and restraint of his victim should consider that for more than half a century at least eight countries have possessed a collective arsenal of, at times, not only scores of thousands of nuclear warheads but the virtually ineluctable means of delivering them. Still, apart from the first and only use of nuclear weapons, in every trying condition, in crisis and in war, in victory and in defeat, not one has been detonated except in test. Who would gamble that if the terrorist enemy possessed even a single nuclear charge, he would fail to devote all his resources to its detonation in the midst of the maximum number of innocents? And though not as initially dramatic as a nuclear blast, biological warfare is potentially far more destructive than the kind of nuclear attack feasible at the operational level of the terrorist, and biological war is itself distressingly easy to wage.

Rising to Meet the Day

I ask again how it is that nowhere is anyone prepared either for naturally occurring epidemics of newly emergent diseases or those that are deliberately induced? It would take whole encyclopedias to dwell on what has not been done and the inadequacy of what little has been done, but a hint may be accurately conveyed by the fact that the nation’s largest biocontaminant unit with fully adequate quarantine and negative air is a ten-bed facility in Omaha, or by the absurdity of a recent announcement from the Washington Hospital Center that in “implementing plans for handling any disaster that might effect our capital,” and “to deal with the worst in biological, chemical, and natural disasters,” it has built, “a multi-use, 20-bed ready room” (emphasis mine).

We may have built a 20-bed ready room, but there is on the horizon a silent wave that is coming at the world, and, if we do nothing, it will sweep over us invincibly. My duties as physician and public official having fused, I propose that we take the measure of this threat and make preparations to engage it with the force and knowledge adequate to throw it back wherever and however it may strike. It need not be invincible and we need not fall to our knees before it. Means adequate to the success of a defensive plan are present in great profusion. Whereas the approaching biological shift is gathering force like a massing army, providence has massed an army to meet it. Having themselves expanded geometrically, the life sciences have come to the threshold of a great age, and to cross it they need only encouragement and a signal from the body politic to put their resources in play.

We are not without weapons in this war. They are present in the stupendous material and intellectual wealth of the civilized world, which, despite current divisions of action and opinion, has everything to lose in common. They are present in the approximately $30 trillion per annum combined gross national products of just NATO and Japan. They are present in the great stores of science and technology amassed over thousands of years of civilization; in the many hundreds of universities, advanced research institutions, and hospitals; in the private sector’s ruthless focus, which, though frequently condemned for its lack of humanity, may yet be the instrument that saves humanity. They are present in the special temperament and brilliance of individual scientists; in the magnificent light that comes of the surprising and ingenious application of new technologies; and in the vigor, intelligence, and decency of free and unoppressed peoples.

The nature of the threat being mortal and reaction to it heretofore irresponsible and inadequate, I propose—entirely without prejudice to the necessity and absent the diminution of the means to disrupt, defeat, and confound the aggressor by force of arms—an immense and unprecedented effort. I see not an initiative on the scale of the Manhattan Project, but one that would dwarf the Manhattan Project; not the creation of a giant, multi-billion dollar research institution, but the creation of a score of them; not merely the funding of individual lines of inquiry, but of richly supported fundamental research, a supreme effort in hope of universal application; not the fractional augmentation of medical education but its doubling or tripling; not a wan expansion of emergency hospital capacity, but its expansion, as is necessary and appropriate, by orders of magnitude; not to tame or punish the private sector, but to unleash it especially upon this task; not the creation of a forest of bureaucratic organization charts and the repetition of a hundred million Latinate words in a hundred million meetings that substitute for action, but action itself, unadorned by excuse or delay; not the incremental improvement of stockpiles and means of distribution, but the creation of great and secure stores and networks, with every needed building, laboratory, airplane, truck, and vaccination station, no excuses, no exceptions, everywhere, and for everyone.

I call for no less than the creation, with war-like concentration, of the ability to detect, identify, and model any emerging or newly emerging infection, natural or otherwise; for the ability to engineer the immunization and cure, and to manufacture, distribute, and administer whatever may be required to get it done and to get it done in time. For some years to come, this should be the chief work of the nation, for the good reason that failing to make it so would be to risk the life of the nation.

It could be very costly, yes, but it is the kind of thing that, once accomplished, is done. And it is the kind of thing that calls out to be done, and that, if not done, will indict us forever in the eyes of history. In diverting a portion of our vast resources to protect nothing less than our lives, the lives of our children, and the life of our civilization, many benefits other than survival would follow in train, not least the satisfaction of having done right. If the process of scientific discovery proceeds as usually it does, diversions of money, energy, and effort into the construction of a vast public and private research and medical system capable of intercepting and defeating the worst natural or terroristic epidemics would very likely bring as well a magnificent offshoot—understanding diseases that we do not now understand and finding the cures for diseases that we cannot now cure. If the laws of supply and demand have not been repealed—and they have not—the heretofore unequaled abundance of medical goods and services would contribute to solving the problems of financing health care—and it would do so the old-fashioned way, by paying for it. And, as always, disciplined and decisive action in facing an emergency can, even in the short run, compensate for its costs—by adding to the economy both a potent principle of organization, and a stimulus like war but war’s opposite in effect, which would power the productive life of the country into new fields, transforming the information age with unexpected rapidity into the biotechnical age that is to come—and all this, if the nation can be properly inspired in its own defense and protection, perhaps just in time.

Rest for a moment what may be your astonishment at the scale of the initiative I have proposed, and allow a conservative Republican from Tennessee, who is by nature skeptical of government action, to affirm the root conservative principle that if the life of the nation is potentially at risk no effort should be judged too ambitious, no price too high to pay, no division too wide to breach.

We have built great cities, dams, and aqueducts. We have built the interstate highway system, bridges, canals, fleets, armies, and a world of structures the cost of which defies expression. We have decided upon going to the moon and then done so in a few short years. Can we not, then, build this thing, and take these steps, to protect our lives and the lives of our children, to evade mass death and alleviate the greatest suffering that man has ever known, that comes to all classes, all races, all ages? Have we been so blinded and confused that we cannot see the single most important challenge before us, and the single greatest opportunity?

I am aware that what is now required has not been asked since the eighth of December, 1941. And I am aware of the difficulties. But I know as well that however much it may be shunted aside by the ordinary and the profane, a deep understanding of mortality, second to none, is present in the people—who are not superficial, who are not to be dismissed, and from whom an almost miraculous collective wisdom has arisen whenever it has been needed. It arose at the time of the American Founding, to create a republican democracy despite the militant opposition of the world’s greatest empire. It arose when the premise of the founding, that all men are created equal, was turned into reality even though to do so meant the bloodiest war in the nation’s history. It arose in the world wars and the Cold War, when the nation fought and persevered for a century, with patience, devotion, and generosity, not merely for the sake of its narrow interests—which some could not even see—but out of principle. I believe that despite their imperfection the sinews of the American people are intact, and I believe that the sinews of our allies and their great civilizations are intact as well.

America on the Front Lines

Especially since September 11th, awareness of mass biological warfare has been at the edge of the popular imagination, but seems to have escaped political will. Blind and chattering elites have dismissed the concerns of the public, or failed to hear them, as if there were a set of facts, a certitude of result, or some infallible wisdom with which to support this dismissal. But no such facts exist and the certitude of those who would discount the danger is just a pose spun from thin air. Failure to foresee, to prepare for, and to forestall bioterrorism and a biological shift is a failure of statesmanship that, until remedies are found and action taken, is also a personal failure for everyone in a high and responsible position—even the highest, especially the highest, including the president, and including me. In this regard the people are ahead of their leaders and possessed of more common sense. They know, quite frankly, that we are as vulnerable as hell, and that no one is really doing anything about it.

The persistent inaction is especially gratuitous in light of the fact that the magnitude of the issue should have the power to heal many a breach and cross many an ideological chasm. For those who hold that attention to moral questions is illusory and impractical, and for those who protest that devotion solely to practical matters is amoral, here is the urgent fusion of both, that cannot be dismissed as either, even if until now it has been perceived and neglected as if it were neither. As in crises of times past, left and right, modernists and traditionalists, the old world and the new, can agree that the protection and preservation of human life on a massive scale is the one goal in their philosophies that will enable their every other principle to seek its every other action.

Conservative predilection and purely empirical observation lead me to believe that what I have proposed, though universal in effect, cannot be brought to fruition as a universal scheme. The World Health Organization is essential, but it works best as an expression of the power and resolution of nations. For the nation is yet the highest level of effective organization, and, paradoxical as it may seem, a worldwide defense against biological catastrophe would be strongest were it erected at the national level, in a loose confederation with unavoidable duplications but with, nonetheless, the organic development among countries of an efficient division of labor.

In this the United States is as blessed as it has been since its beginnings. We are the wealthiest, freest, and most scientifically advanced of all societies, the first republican democracy, the first modern state. And although we have suffered criticism of late and to no small degree because of our awkwardness as a young nation, we have been willing since our Founding and are willing still to pursue certain ideals. Though not infrequently condemned from the precincts of cynicism, America has mostly left cynics in its wake, sometimes after saving them from floods that they themselves have unleashed.

Do not discount America or dismiss its resolution. Our imperfections are accompanied by fine qualities and beliefs of which we will never be ashamed and from which we have no intention of recoiling. We believe in government with the consent of the governed, and in the sanctity of the individual. We have as a nation by and large rejected a mechanistic view of human nature in favor of a belief in the soul and the grace it may be granted. (If there is no soul, what is the basis of human equality in law or morals, given that we are unequal in all other ways?) This belief to which we hold firm is descended from our founding, which occurred at a time of miraculous poise in human history when science and reason were in uncontradictory balance with faith; when in America the freshest optimism the world has ever known was tempered by a view of human nature unsurpassed in its clarity and caution.

Lest this seem too abstract, consider that when we found ourselves in violation of our elemental principles we suffered through many years of fratricidal warfare to put them right. Both sides fought with inimitable courage, and the side—of which I am a son—that was reduced to waste and ash, rose from its ruins to fight a greater battle, a battle with itself, finally to embrace the principles it had opposed.

From the blood of my fathers and in my blood itself I have not merely a vision of ruin, waste, and ash, but the certain knowledge, a vivid memory that has of late been refreshed and confirmed. This is not the last time you will hear from me, but today I have tried to impress upon you the urgency I feel in the matter of the immediate destiny not only of America but of the world, for pandemics know neither borders, nor race, nor who is rich nor who is poor, they know only what is human, and it is this that they strike, casting aside the vain definitions that otherwise divide us.

It is my pre-eminent obligation as a public servant and my sacred duty as a physician to ask you to support the essence of my proposal. In respect of human mortality, for the sake of your own families and children, for the honor and satisfaction of doing right, and to sweep away the inexcusable prevarication that has accumulated since the great shock of September 11th, I bid you join in this declaration. May God preserve us all, and may our actions and foresight make us worthy of His preservation.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The coming great awakening.

Our Covid-era oligarchs are fitting us for feudalism.

A little less conversation, a little more action.

In real life, trade-offs abound.

A field guide to manning up in an incapacitated age.