Christians need to find the will to act.

The Case for Christian Civilizationism

Prioritize the civilization that has always been over the nation that never was.

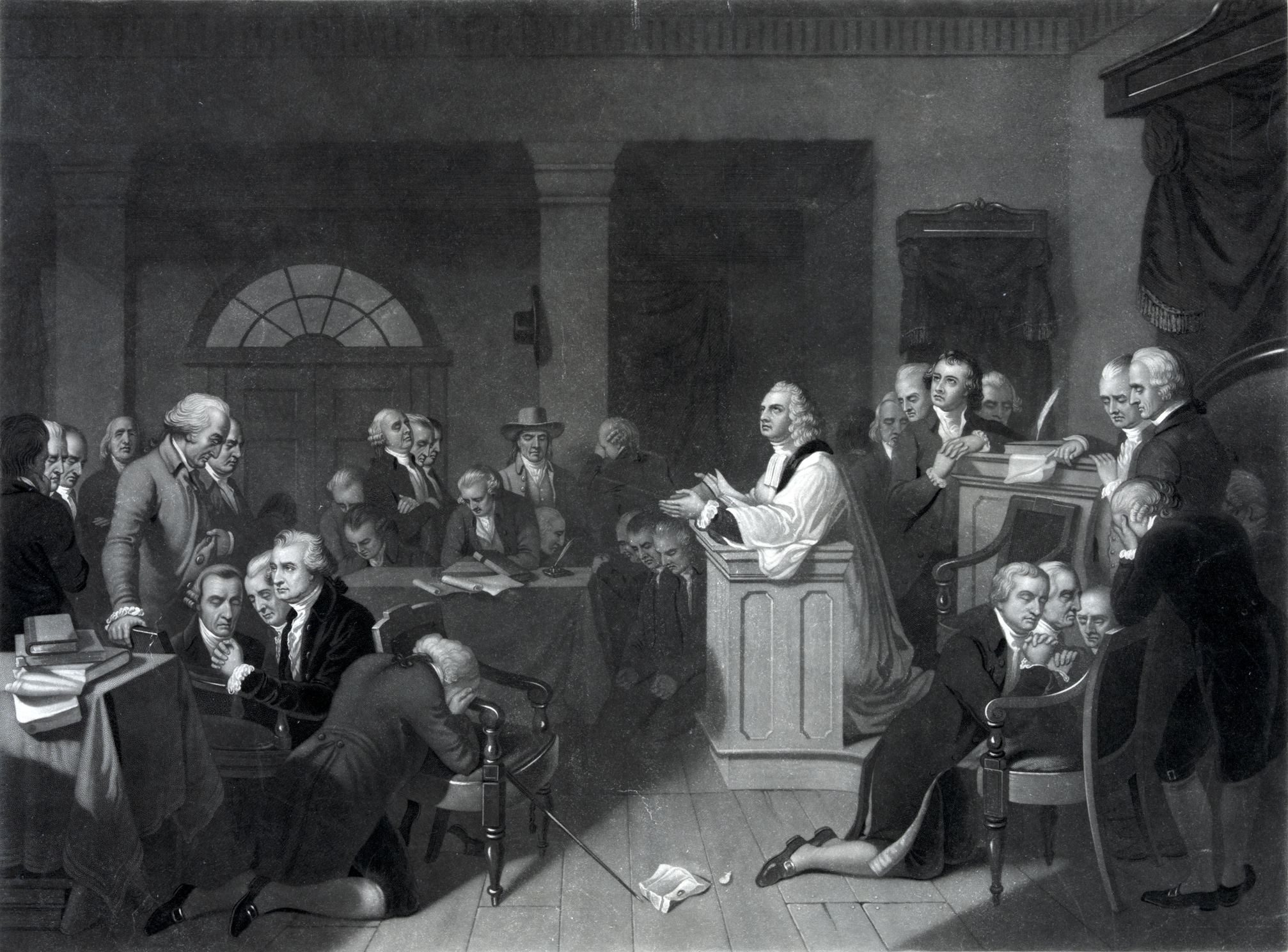

Image credit: Cross at Sunset, Thomas Cole, 1848, unfinished

Christian nationalism has become a bandwagon. For some, that’s reason enough to avoid it. For others, that’s a good reason to jump aboard—in hopes it takes them where they want to go.

But where is that? I do not believe those who have jumped on the Christian nationalism bandwagon actually want a Christian nation. Rather, I suspect the yearning they have is for a Christian civilization. They recognize that Christianity and civilization are inseparable, that each is best expressed when the two are most in tune, and that there should be no hesitation to use politics toward this end.

But acknowledging this greater truth also means recognizing that nationalism of any kind can only be a stepping stone toward the ultimate goal. If harmonious Christian civilization is the destination, the wagon should not simply crash headlong into American political advocacy, capturing seats of power to codify Christian ethics, or using the power of government to evangelize. Rather, those who want Christian civilization should prioritize re-Christianizing America, not re-nationalizing Christianity.

This is not the same as retreating, as many Christian figures have, to the safe limitations of “private faith.” The injunction to “Evangelize your neighbor” does not absolve one of responsibility for one’s vote, voice, or vocation. Indeed, evangelism and socio-political action are intrinsically linked; many have come to Christ because of the moral example and attractive leadership of a politically active Christian. Christians must all be open advocates for Christianity. But their victory condition should not be passing pro-Christian legislation. It should be the conversion of souls.

This anagogical approach to the question of faith and culture provides an important corrective to Christian nationalist messages that are unhelpful or self-defeating. Aaron Renn is correct in that “Christian nationalism” is a term with no historical significance or cultural context in America, and therefore is not especially helpful for either intellectual or branding purposes. In Europe, “nationalism” is a useful term with a clear definition. But America is not a true nation-state now and arguably never has been, though it could have been at times in the past. Today, it is as a civilization-state (albeit one in denial) with an empire in decline.

The illusion of American unity began after the Civil War and was sustained by her successive military victories against the powers of Europe and Asia. The Spanish American War, the First World War, and especially the Second World War united us in the shared adrenaline rush and economic high that came from despoiling our enemies. We assumed the mantle of a protagonist on the world stage: the primary defender of Western civilization, with its putatively liberal civic principles, and its tolerant Christian virtues, against the atheistic, totalitarian, intolerant Communist Russia.

The ensuing Cold War kept Americans in a heightened state of danger, but it also inspired us to build. We took on the task of colonizing Europe culturally and globalizing Japan economically, with astounding success. For two decades Americans felt unstoppable—and our government began acting like it was, not just around the world, but in the homeland.

The power of the bureaucracy and its three-letter agencies rapidly expanded as power concentrated at the center, all under the management of competent public servants, engineers, scientists, and builders who had been baptized in war and steeped in patriotism.

All these factors drew our grandparents and parents together. Unbeknownst to them, though, the ties that bound America itself together were beginning to loosen. Communism and its religion of cultural Marxism may have been held at bay on the battlefields of Korea, but it overran the sandbags in our own elite institutions, producing wave after wave of a mass intelligentsia to populate the professional managerial class and the cultural centers of art, literature, and fashion.

Meanwhile the memory of military victory on a grand scale faded. We had prepared for half a century for another global war of an existential nature that never came. Terrorism and an ostensible security emergency united us for a brief moment at the turn of the 21st century, but unity in victory eluded us.

With no more enemies of consequence to defeat on the battlefield, Americans and their government turned all attention to enriching themselves, primarily with the mechanisms that the 20th century had provided for the nation’s perpetual state of low-grade emergency. Rather than scaling down the federal government’s role in the economy and in public life, five successive administrations under Clinton, Bush, Obama, Trump, and Biden scaled it up. The pedal hit the floor with Obama: the mass intelligentsia, educated by ideologues, began the crusade of a Second Reconstruction. The ironic catchphrase “Thanks, Obama” encapsulates rural Americans’ suffering under the de-industrialization and deracination produced by federal policy—and the blue city dwellers’ ecstasy over government cash, cheap foreign labor, and high demand for emerging tech skills. Not until the populist uprising that led to Trump’s single term did it finally dawn on many Americans that we are “divided.”

But division is not what ails America. It is our insistence on being united as a nation when we never truly matured into a nation-state. We grew up too fast. A centralized American government managing a modern nation state is incapable of bringing about the civilization we want.

It is likely too late for us to have a united nation of the kind envisioned by 19th-century luminaries—but it is not too late to have a civilization. If we truly want the civilization that America inherited and became the caretaker of, we must change how we imagine the U.S. and Christianity’s place in it.

A Light to Lighten the Nations

There is plenty for Christians to do politically short of indulging in Christian nationalist pipe dreams. Forget capturing the federal government for the purpose of cracking the whip of Christian morality to “unify” Americans who don’t want it. Instead, why not simply advocate for the restoration of American governance at its best—at its most disunited? A loose union of localized states with concentric rings of representative governance would allow those who wish to live in virtue and preserve Christian civilization. The freedom of association, limited government, and natural law are enough to bring about safety, prosperity, and growth for those who are capable of self-government.

In such a system, sorting on moral lines is natural. Those who wish to live with Christian values (or at least their societal benefits) in their lives will do so, while others who do not can try their luck with Atheism or perhaps Islam, short of anarchy. The results will speak for themselves.

Christian nationalism struggles to reify an immature American “nation” with its unwieldy, crumbling government, and thereby leaves no room for this ideal resolution whereby Christian civilization could continue and flourish. I wonder if those proposing a march through the national institutions to the tune of “Onward Christian Soldiers” have confidence in the ability of Christianity to speak for itself, to “out-govern” other moral systems.

This is not defeatism. It is a healthy dose of realism that is based on an ultimate idealism rather than misplaced fanaticism. Visions of a maximalist takeover are, in any case, more the creation of a hostile opposition than a serious proposal native to the Right. In the ’80s and ’90s there was the liberal panic over a “theocracy”; in the 2000s, it was time for “fundamentalism” to reenter the cultural lexicon. Now the term is “Christian nationalism”—an imagined secret cabal planning a dangerous theocratic coup.

As a popular brand and as a policy position, this “Christian nationalism” has as much chance of winning as reparations has for the Left. There is too much need for nuance in its definition. Those who like it would generally prefer to avoid the baggage of associations, and those who dislike it are unlikely to overcome their repulsion through further explanation. Most will just default to the easy explanation provided by Google—and the salivating secularists will have their bogeyman.

Better, then, simply to effect advocacy for Christian values under other names and by other means. Activists for reparations by other names don’t go around advocating for “free money,” as honest as that might be. They talk about “social justice” and “equity.” Similarly, a Christian political movement should not brazenly call for Christian theocracy when Christians themselves would be satisfied with Christian civilization.

With some loud exceptions, American Christians do not want an explicitly Christian nation, but rather an implicitly Christian civilization. And we should be wary of those loud exceptions, because they create easily-defeated caricatures of our deeply-held beliefs—and they are rarely unmotivated by personal gain. Going overboard on social media or in the opinion column to gain a following is not why we are Christians. Our God has already proven Himself throughout history as being a God not of a nation or a church or a kingdom, but a civilization. I am a Christian because I want to be like the God I worship and have found this godliness to beget a superior way of living for myself and those around me.

History validates me and millions of Christians throughout the ages in this belief. The West stands because of Christians, and until recently Christians have flourished in the West. From Rome to Britain to America, Christians have found value in a republican government, a charter of rights for citizens, and a healthy non-governmental religion of virtue, honor, and charity.

An intellectually honest person with no personal axe to grind against Christianity will look at history, far and near, and see that traditional Christian values have upheld the installation of liberal principles in civic life. It’s not as if the Enlightenment or the Constitution somehow created order out of chaos—these ideas were themselves outgrowths of Christian civilization.

We must preach Christianity’s contribution emphatically and unapologetically. But then we must go further. We must prove the truth of our words by our own lives; by the way we care for the bit of civilization we have been entrusted with—our homes and land, our children and spouses, our churches and cities, our enterprises and institutions.

I want a civilization Christianized not by mere laws or cultural artifacts, but by the genuine faith of the people who live there. The path to that civilization is not to take over the federal government. To use a biblical analogy, we don’t need to storm the palace of Ahab and Jezebel, or even the temple of Baal. We need a showdown on Mount Carmel, with all the people gathered to see Christian civilization and secular atheist civilization confront one another as opposing ways of life. Let the God who answers with results be God. Christians, for their part, should do what Christ commanded: “let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good deeds, and glorify your Father in heaven.” When we live in goodness and godliness, the results in our own lives will speak for themselves. If we are faithful, maybe one day even unbelievers will voluntarily ask us to rule in their affairs.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

It’s far more than the latest ad hoc term for everything the regime despises.

Christian nationalism is a long overdue attempt to revive American’s political and cultural heritage.

It takes more than online wishcasting to win elections.

Some labels are just about chasing normal people out of the polite mainstream.

A time for choosing.