Christians need to find the will to act.

No Other Gods

Because Christianity is an incarnational faith, it must have a visible expression.

Rob Reiner is going after Christian nationalism. I don’t recognize anyone in his movie other than David French, who is exactly the sort of person I would expect to be in this movie. David French is a former writer for National Review and a libertarian, or neoconservative-minded, right-winger. But he wrote for conservative publications and was a member of conservative organizations. And then Trump radicalized him. Now he’s pretty clearly on the Left. He was writing for The Atlantic for a while, and now, I think, he’s writing for the New York Times.

His raison d’être appears to be to attack from the authority of an American evangelical—a conservative but not that kind of conservative, a court jester in the kingdom of liberalism. From his self-styled identity as a Christian conservative, he attacks conservatives, and he attacks Christians. Now the reason I don’t know anyone else—and the only reason I know David French is because he ran in conservative circles for some time—is that it’s all Protestants in this movie. There are no Catholics. It’s no knock on Protestants; it’s certainly no knock on evangelicals. Many of my best friends are evangelicals and Protestants! But I’m not—I’m a Catholic, and so I’m just not as familiar with these leaders of the evangelical movement.

So why is that? Why is it that it’s just evangelicals who are in this movie? It’s no knock on evangelicals exactly, but it’s more to do with Christian nationalism. Christian nationalism is a fundamentally Protestant movement.

Now, in practice, I support Christian nationalism. And, in practice, I guess David French and those evangelicals in this movie oppose Christian nationalism. The reason I support Christian nationalism, practically, is because we have a nation. I respect our nation. I’m a patriot, love my country. It’s an extension of filial piety. And the soul of our nation is Christian.

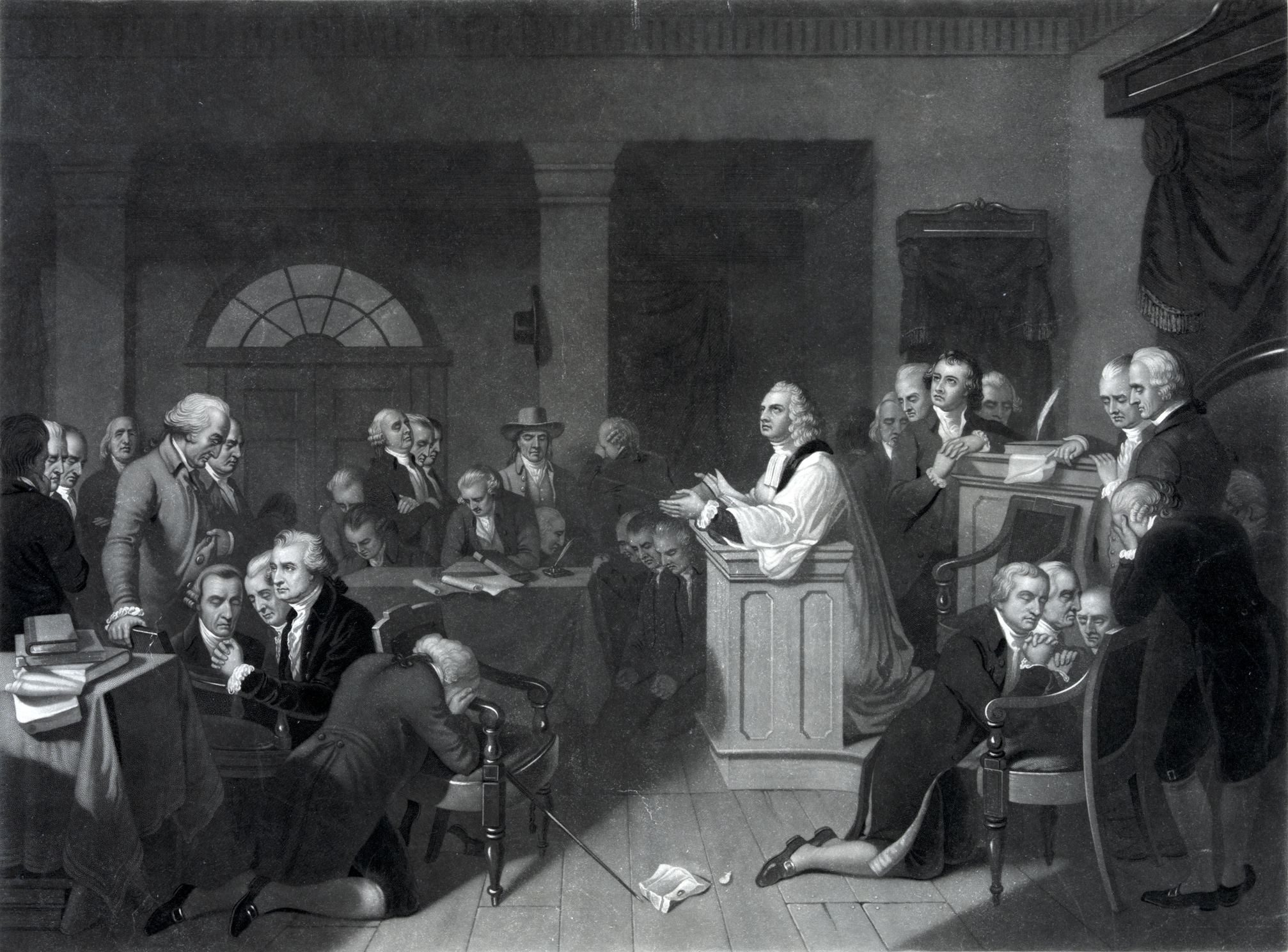

It was founded explicitly as a Christian nation in 1620 by the pilgrims at Plymouth Rock who sailed here on the Mayflower, which is also the name of an excellent brand of cigars. And the leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony called this “a model of Christian charity,” a “shining city on a hill.” Our Founding Fathers spoke in broadly Christian terms. John Adams said that our morality in America would have to be a Christian morality. John Jay said exactly the same thing. George Washington gave thanks to God. Abraham Lincoln never wrote or spoke without in some way channeling the King James Bible. We’ve got “In God We Trust” on our money. It’s a Christian country. Most people are Christian. There’s no other way to put it.

So, if we’re a nation and we’re going be Christian, well, I guess that’s Christian nationalism, right? But liberals don’t like that, because liberals don’t like Christianity and they don’t like nation-states. What they want is liberal globalism.

Now, the reason I say Christian nationalism is fundamentally Protestant is because nationalism is fundamentally Protestant. Nationalism is a product of the Westphalian system, the Treaty of Augsburg and the Peace of Westphalia, which put an end to the religious wars that came about as a result of the cracking up of the unity of Christendom. So, before all of that happened, Europe—Christendom broadly—was united in one faith with lots of different political entities. But there was a connection between the unified faith and all of the different political entities, notably the Holy Roman Empire, but even other little political entities. And, therefore, the civilization had a unity.

We all had the same faith—and that faith was expressed visibly in political life, because our faith is an incarnational faith, because our Lord is incarnate. He’s not just floating in the sky. He enters into history in time and space. He picks specific apostles. He gives them the keys to the kingdom of heaven. He says “go forth and make disciples of all nations.” He says “feed my sheep.” He says “on this rock, I will build my church,” Simon Peter. (You’re now Peter, which means rock.) He says these things, and then there’s a visible expression. And the apostles go off to all the corners of the world. And Saint Thomas makes it all the way to India, and Peter and Paul go to Rome.

What separates Christianity from other religious traditions is that you can trace it through journalism. You can trace it not just through philosophy or abstract theology, but with real people in real time and space. There’s an apostolic succession going all the way back to our Lord. Which means that if you are Christian, you must believe that the faith has some kind of physical expression and a community expression.

Unfortunately, though, certain branches of branches of sects of branches of modern Christianity have ignored all of that, and they want to abstract everything about the faith. And they want to make religion something that you just do in your own little head, maybe quietly at night in your room, that has no visible expression anywhere. But we can’t do that.

Christianity spreads as a community. Because we are social creatures, because we are the political animal, even the very ability to pray will expand or diminish based on political circumstances. Do we live in a culture that’s conducive to prayer, that’s conducive to the flourishing of the religion or not?

Don’t forget, Christianity is not a polytheistic religion. Our God is a jealous God and will have no other gods before Him.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

It’s far more than the latest ad hoc term for everything the regime despises.

Christian nationalism is a long overdue attempt to revive American’s political and cultural heritage.

It takes more than online wishcasting to win elections.

Some labels are just about chasing normal people out of the polite mainstream.

A time for choosing.