Middle Eastern despots destroyed the competing sources of authority on which new societies could be built.

Neoconservatism: The Lessons Learned

A brief guide to putting America first.

Irving Kristol defined a neoconservative as a liberal “mugged by reality.” A select number of these erstwhile liberals wisely chose to hand over their valuables to their muggers—in this case many of the comforting sociological illusions underpinning President Johnson’s “Great Society.”

Decades later a new type of neoconservative emerged. This second generation, perhaps determined that no future “muggings” should occur, launched what could well be the most awesome and devastating counter-assault on reality in recent political history.

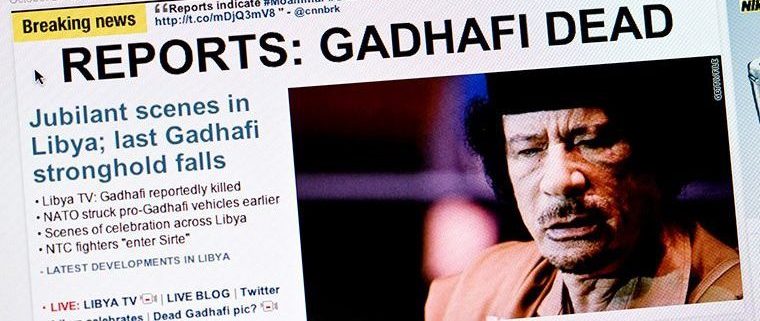

Fortified with a mixture of Post-Cold War triumphalism and universalist illusions of spreading global democracy, this neoconservative cadre focused their efforts on foreign, rather than domestic, policy. But the crown jewel of its military adventures, the Iraq War, was also its crowning disgrace.

The roots of that grievous error showed clearly in the Republican establishment’s reluctance even to acknowledge it—much less attempt to learn from it. Of the sixteen candidates in the 2016 Presidential primary, thirteen years after then-President Bush declared “mission accomplished,” only two dared criticize the Iraq War and the experts behind it. One, Donald Trump, won the Presidency in a stunning victory against the vigorous opposition of the GOP establishment and its powerful institutional allies around the Western world.

With this victory, the failures behind the neoconservative foreign policy establishment, particularly in the Middle-East, could no longer hide behind embarrassed silence. But it is not enough to smugly point out failures. In order to seize the opportunity Trump’s presidency created and to develop a successful foreign policy vision for the 21st century, we must learn from those failures. Two general lessons are especially noteworthy.

The first lesson relates to the faulty “blank slate” conception of human nature that implicitly informs the neoconservative’s democracy-building agenda—at least as it is presented rhetorically. What, after all, must one presuppose to think that once a far-flung dictatorship is deposed, a free society with thriving democratic institutions can be set up de novo, like a McDonald’s on an empty lot?

For one, it would be necessary to dismiss as irrelevant the fact that the people of the (former) dictatorship had no history of maintaining or creating such institutions. The newly liberated would be seen to need only to favor certain abstract universal principles—equality, freedom, human rights—and the institutions would mostly take care of themselves. In fact, however, the notion that a people’s deeply rooted histories, cultures, and other endowments are largely immaterial to its range of immediate political possibilities turned out to be a dangerous fiction.

A more humble, sober, and in fact traditionally conservative understanding of politics and human nature cautions against ambitious projects of democracy promotion, especially in regions that lack the preconditions for it. Theoretically a thriving democracy would be preferable to a strong-arm dictator; yet a strong-arm dictator, especially a secular one, is vastly preferable to the bloody chaos of Islamic radicalism and civil war. A foreign policy that reflects reality in this way—one that puts America first—takes to heart the examples of Iraq, Libya, and now Syria. It embraces the sober restraint of a more conservative understanding of human nature than abstract principle alone allows.

The lesson concerning the limits of of “blank slate” thinking has an important corollary. If liberal democratic institutions cannot simply be transplanted into nations whose people lack the historical, cultural preconditions to successfully maintain them, nations that do possess those preconditions and institutions ought to observe a cautious and at times restrictive immigration policy toward those nations that don’t—especially where radical Islamic terrorism is prevalent. The neoconservative failure to appreciate these co-related insights resulted in rather bizarre parameters for public discourse. It was politically acceptable to advocate for bombing, military intervention, and regime change in various Mideastern nations, yet impermissible to suggest restricting immigration from them. America demands better.

In that sense, President Trump’s “travel ban” represents a clear and welcome departure from neoconservative orthodoxies. Any post-neoconservative, America First foreign policy must consider how foreign policy objectives might be achieved more effectively, humanely, and cheaply through reasonable immigration control.

If our first lesson from neoconservatism cautions against military intervention on the basis of a flawed understanding of human nature, the second lesson urges not to go so far as to oppose military engagement as such. The answer to neoconservatism is not isolationism. In fact, the answer should be closer to a rejection of “ism” as a foreign policy heuristic in favor of more material and reality-based considerations. Which peoples, factions, industries, or nations benefit from a particular foreign policy stance? An America First foreign policy is not necessarily a Raytheon First foreign policy.

But some military engagement, even apart from defensive war, is necessary to serve American interests. In order to separate those legitimate cases and objectives from those hawked by naïve ideologues and special interests, an America First foreign policy should pay careful attention to the relation between the demands of energy, financial and monetary policy, and geopolitics. These more complicated considerations are, of course, almost never discussed on the cable shows.

The final lesson to draw from neoconservatism has to do with the relationship between foreign policy and morals and values. While the first lesson cautions against the feasibility of exporting our norms and principles, this final lesson pertains to the desirability of exporting our American values, whether militarily or by other means. A decisive consideration in this regard is the merit and desirability of these values themselves.

The past several decades have seen the cultural ascendance of a militant form of doctrinaire progressivism as a dominant institutional “value,” including within the military bureaucracy itself. The more entrenched this becomes, the more the heir to the neoconservative vision of projecting American values abroad will begin to look like an imperialistic project to make the world safe for gender neutral bathrooms. Already one sees this transformation in the kind of hawkish rhetoric that urges us to teach Putin a lesson for not sufficiently embracing gay rights.

This is to say that the desirability of exporting our values and institutions, perhaps militarily, partly turns on our evaluation of the health of those values and institutions at home. The election of Donald Trump both responded to and exposed a deep crisis in institutional legitimacy here at the home front—indeed, from the high level corruption of the FBI, CIA and DOJ to the thorough corruption of the media it has exposed how our nation’s most powerful institutions have been neglectful of, and possibly hostile toward, the interests of regular American citizens.

This points to the final, perhaps most important lesson from the death of neoconservatism. Neoconservatism is in many ways marked not just by a particular foreign policy vision, but the prioritization of foreign policy in relation to domestic concerns. An America First foreign policy must recognize that the chief threat to America, and indeed the West, is not an overseas regime like the Soviet Union or a foreign-born movement like radical Islam. To the contrary, it is a home-grown threat: the corruption and de-legitimization of our domestic institutions and the elite entrusted with the custody of the American way of life.

Hard as it may be, a post neo-conservative America First foreign policy must first recognize that the chief struggle for our nation’s future is taking place right here in America.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

To rethink American foreign policy, we must recover the principles and purpose of American government.

The hard lessons of neoconservative foreign policy's failure.