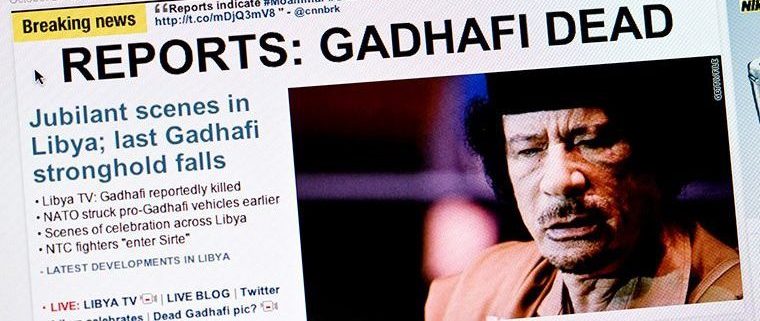

Middle Eastern despots destroyed the competing sources of authority on which new societies could be built.

Claremont vs. Foreign Policy Establishment

To rethink American foreign policy, we must recover the principles and purpose of American government.

Why did the American foreign policy establishment fail? It deviated from the principles and purposes of American government. Not all those associated with the Claremont Institute agreed during the failures of the last two decades. Many, like most of the nation (including myself), originally supported the Iraq War.

Yet, since the turn of the century, Claremont Institute Senior Fellows have consistently pointed out the deficiencies of the foreign policy establishment. While much of the traditionalist Right flirted—or more—with isolationism, Claremont rejected neoconservatism by pointing to a Constitutional, and distinctly American, approach to war and peace.

Codevilla’s War

Claremont Institute Senior Fellow Angelo Codevilla argued tirelessly that experts—Right and Left—hastened their fall in three interrelated ways. They overreached in their efforts to remake regimes, confused friends and enemies, and failed to define victory clearly enough to achieve peace.

Soon after 9/11, Codevilla insisted that America must eliminate actual, specific enemies—rather than nation-build amidst “war” on terrorism, or any -ism. “Virtually all America’s statesmen until Woodrow Wilson warned that the rest of mankind would not develop ideas and habits like ours or live by our standards,” Codevilla noted in his 2001 essay “Victory: What it Will Take to Win.” “Our peace, our victory, does not require that the peoples of Afghanistan, the Arabian Peninsula, Palestine, or indeed any other part of the world become democratic, free, or decent.” What the national interest demands is “only that the region’s leaders neither make nor allow war on us, lest they die.”

As Codevilla reminds us, though Wilson devised the League of Nations “to improve the world . . . when Senators asked him how his commitment to everlasting peace differed from a commitment to perpetual war, he was unable to answer.” In effect, “Wilson erased the distinction between war and peace”—and “American statesmen have yet to redraw it.” In sum, the American foreign policy establishment believes that “wars are now endless, and meant to be managed by experts.”

Experts delight in endless problems, and the job security of procedures to match. But their track record has long been suspect. Codevilla harshly critiqued the intelligence community decades before its role in promoting the Iraq War—never mind the 2016 election and its aftermath. In 2002, he advised his critics and readers of the Claremont Review of Books that “U.S. human intelligence is almost perfectly incompetent,” suggesting that the Intelligence Community told politicians what they wanted to hear while working for its own interests and covering up its transgressions. 9/11, in that sense at least, changed nothing.

When it came to “regime change,” Codevilla drily pointed out that “few in Washington or academe even know what the word ‘regime’ means.” The result of assuming all mankind would readily adopt our “ideas and habits,” and seeking on that basis to make “the world become democratic, free, or decent,” was an endless cycle of meandering military interventions absent clear victories, and therefore absent peace. At its most extreme, he predicted, this form of neoconservative foreign policy would lead to the sort of political tumult we are now experiencing.

“The United States is not at peace, and it is not making war. To this extent alone the accusation of empire—the dawdling kind that wastes its core resources—sticks. If we continue to trifle with empire rather than establishing peace, we shall reap stalemate, retreat, and the domestic strife that is empire’s bitterest consequence.” Endless war could never deliver perpetual peace—even at home. Our “domestic strife” is fueled by the stinging recognition that the leaders of both parties eagerly squandered blood and treasure on the basis of faulty assumptions.

Small wonder the American people distrust their elites. “Confidence is even more essential to polities than to economies. Nothing destroys a people’s confidence in its way of life more surely than the impression that the people-in-charge are incompetent, and nothing earns that impression more surely than a government’s failure to provide safety. That is why the U.S. government’s failure to win (in the true sense of the word) the war on terrorism . . . would have consequences for America far worse than the ones that befell when ‘the best and the brightest’ botched the Vietnam War.”

Codevilla warned of “a raw deal” for “conservatives, following their natural inclination to ‘support the president,’ were left holding the bag for yet another botched war,” yet this, of course, is exactly what happened—prompting, to the shock of the establishment Right, the eventual election of the one Republican presidential candidate willing to blame the GOP as much as Barack Obama. “The Bush team is composed of the best and brightest of its generation,” Codevilla said. “Perhaps, then, anything like victory must await a time when America is governed by simpler creatures.”

Know Thyself

The underlying problem, as Professor Harry V. Jaffa warned in his 2006 essay “The Central Idea,” is that America can’t give to the world what it fails to understand about itself. This unforced crisis stems from our conflicted ignorance and vehement disagreement about the principles of our civic life, and our corresponding lack of clarity concerning our national purpose. Ignorance and disagreement about human nature prevent us from governing ourselves well, much less other nations.“Our government assumes that the people of the Middle East, like people elsewhere, seek freedom for others no less than for themselves. But that is an assumption that has not yet been confirmed by experience.”

“Our difficulty in pursuing a rational foreign policy in the Middle East—or anywhere else—is compounded by the fact that we ourselves, as a nation, seem to be as confused as the Iraqis concerning the possibility of non-tyrannical majority rule,” Jaffa emphasized. “We continue to enjoy the practical benefits of political institutions founded upon the convictions of our Founding Fathers and Lincoln, but there is little belief in God-given natural rights, which are antecedent to government, and which define and limit the purpose of government. Virtually no one prominent today, in the academy, in law, or in government, subscribes to such beliefs. Indeed, the climate of opinion of our intellectual elites is one of violent hostility to any notion of a rational foundation for political morality. We, in short, engaged in telling others to accept the forms of our own political institutions, without any reference to the principles or convictions that give rise to those institutions.”

Misunderstanding Liberty

In their place, our leaders adopted faulty, ill-considered assumptions about human nature and political life, as Charles Kesler maintained in his 2005 essay “Democracy and the Bush Doctrine:”

“It is one thing to affirm, as the American Founders did, that there is in the human soul a love of liberty. It is another thing entirely to assert that this love is the main or, more precisely, the naturally predominant inclination in human nature, that it is ‘a power that cannot be resisted.’ In fact, it is often resisted and quite frequently bested, commonly for the sake of the ‘food and water and air’ that human nature craves, too. The president downplays the contests within human nature: conflicts between reason and passion, and within reason and passion, that the human soul’s very freedom makes inescapable. True enough, ‘people everywhere prefer freedom to slavery,’ that is, to their own slavery, but many people everywhere and at all times have been quite happy to enjoy their freedom and all the benefits of someone else’s slavery.

“President Bush, in effect, plants his account of democracy in common or shared human passions, particularly the tender passions of family love, not in reason’s recognition of a rule for the passions. He does not insist, as Lincoln and the founders did, that democracy depends on the mutual recognition of rights and duties, grounded in an objective, natural order that is independent of human will. Bush makes it easy to be a democrat, and thus makes it easier for the whole world to become democratic . . . .”

“Unfortunately, the administration has never thought very seriously about constitutionalism, either at home or abroad, except for the narrow, though important, issue of elections.”

Even as Iraq was liberated from Saddam Hussein, Kesler cautioned that “as we cheer the lengthening roster of democracies, we should wish for them, and for ourselves, the self-control that keeps liberty a blessing and not a curse”—a mission far from accomplished, if it was undertaken at all.

Foreign Policy, Rightly Understood

In “Leo Strauss and American Foreign Policy,” Claremont Institute Senior Fellow Tom West, in the wake of the invasion of Iraq, set out a corrective to neoconservative foreign policy. While “neither Strauss nor the founders were isolationists,” West contended, they adhered to a classical western tradition at odds with neoconservatism, influenced, as it was, “by the political principles of American Progressivism—of modern liberalism.”

However well-intentioned or fashionably up-to-date, “the purpose of foreign policy should be limited to self-preservation or necessity,” West concluded; “all policy, foreign and domestic, should be in the service of one thing: the well being or happiness” of American society.

The Founders well knew it wasn’t “the obligation of one nation to solve other nations’ problems, no matter how heartbreaking”—not out of any mean egotism, but because such an ill-thought crusade would “violate the fundamental terms of the social compact,” and the natural law behind it. “For Strauss and the classics, that would be a distraction from the highest purpose of politics, self-improvement through the right domestic policy.” As West explained, “the foreign policy of Strauss and the classics seeks neither hegemony over other nations nor benevolence toward other nations.” By contrast, “its inherent moderation makes it in effect benevolent, especially in contrast with the kind of imperialism practiced by regimes that merely want to lord it over as many nations as possible.” The Founders’ “anti-imperialist conception of foreign policy,” wrote West, “rejected Machiavelli’s belligerent republicanism, with its celebration of hegemonism and conquest,” restoring “a proper restraint on the dangerous human passion to dominate others, both at home and abroad.”

“We must not forget that in the end, war, like all public policies, must serve what Strauss, the classics, and the founders regarded as the purpose of political life—namely, the cultivation of ‘peaceful activity in accordance with the dignity of man.’”

Recovering Our Foreign Policy

There is much work to be done in order to develop a working framework for how American government ought to interact with the rest of the world in the 21st century. But the foundation of that work is not at all in question. The failure of the neoconservatives’ grand designs revealed the direct, causal influence that our understanding of human nature and human governance exerts on policy and political action. Herein lies today’s opportunity—and our urgent need—to recover the American Idea.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

A brief guide to putting America first.

The hard lessons of neoconservative foreign policy's failure.