Two course corrections, one trajectory: Reformicons and Populists need each other.

Why Bother?

Nationalism confronts the question our elites struggle to escape.

Over the last decade, the “negative” states of the American mind, decried by pundits Left and Right, could be categorized as ironic resignation and vengeful disillusionment. Online, people pay a lot of attention to these mental states. In the first case, the internet has seemed to reward people who (can) shrug smugly and laugh out loud that nothing matters, while they go on pouring their life force into expertly curating consumable content. In the second, the internet has organized and mainstreamed people whose idea of justice is punishing the people, organizations, and institutions that (they say) have deprived us of what would have otherwise been a golden age of safety and flourishing. These two developments have been associated with a new culture of nihilism.

But a third frame of mind has been lumped in with the nihilistic trend.

Many Americans despair of their situation without much irony or vengefulness, unable or unwilling to draw personal and cultural strength from resignation or disillusionment. They may strike critics as just another strain of “negative” nihilists who must be re-educated to gladly accept a role in improving society’s mood. But something else is going on.

It is becoming harder and harder to convince people to take on burdens for the benefit of society, however defined, when so many are struggling to see why they should bother trying to work, raise a family, plan for the future, keep up with technology, participate in civic life, and tune in to mass entertainment. In today’s society, where political agency is increasingly reserved for elites enriched by machines—and the official victims those elites choose to credential and reward—traditional moral and cultural practices are growing increasingly costly for those engaged in them. The barriers of entry are rising steeply for those trying to live up to old family and community standards of rectitude and flourishing, especially those trying a second or third time around.

At the same time, even the costs of self-medicating the pain of falling short of traditional standards of choiceworthiness, duty, integrity, and identity are rising. Partying and gaming are losing their staying power as consolation prizes. The moral significance and sense of pride belonging to the Romantic rebel character has been leached away in the new society. Technology, with its endless supply of entertainments, diminishes our stature in our own eyes apace with the diminishing meaning-value of fun and games.

The ironically detached retreat ever more archly into ever more recondite forms of curated self-expression; the vengefully disillusioned ever more bluntly vent their fury however they can. The Americans who want to bother laboring for lives of durable, ultimate meaning, however humble, find the attempt ever harder, ever lonelier. These latter Americans are from different classes, but united in their struggles with despair. They present a unique political problem distinct from their nihilist cousins. Yet the dominant culture, now hostile to them, responds with the same offer: put justice—the dominant culture’s vision of justice—first, or be plowed under.

The dominant vision of justice is the now-familiar one in which our social good is determined by a fixed elite of social scientists. The job of these experts is to orient government and society around redistributing power, prestige, and pride to groups whose promotion is seen as progressively perfecting society itself.

This social-justice vision achieved traction for two main reasons. The first is that it best answered the “why bother” question as it arose in post-industrial but pre-digital society beginning in the 1960s. The response to the anxiety-inducing question of what all the upwardly mobile beneficiaries of that society were actually supposed to do was simple: reconcile establishment and counterculture, governance and artistry, through a new industry with a new form of rule. The social-good regime demanded a huge new (and initially well paid) class of elite analysts, communicators, interpreters, celebrities, engineers, and credentialed dreamers, whose shared goal was convincing everyone to organize their lives primarily around the pursuit of ever more perfect justice at every social scale, but definitively the global scale.

But the second reason for the triumph of this model is that post-industrial America faced a wave of disillusionment if it tried to place faith in either dominant cultural camp alone. On its own terms, the counterculture quickly degenerated from dream into nightmare—little more than the ideology of crime, especially rape and murder. But the establishment failed the imagination too: “ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country” degenerated into Vietnam. At the same time, the industrial-age model of life as a lonely homebound housewife or a lonely officebound man in a gray flannel suit also failed, not just in the realm of dreams but in the daily grind of reality. The only question left to ask, it appeared, was what you and your country could do for society—for humanity. The alternative—with the great, silent majority lacking the juice to nationally restore their traditional authority—was the abyss.

Clinging to this question did ultimately set American culture on a relatively stable new foundation: a seemingly triumphant post-Reaganite “New Democrat” foundation that refused to stop thinking about tomorrow. Until, that is, tomorrow—in the form of today’s dawning post-post-industrial, digital age—betrayed the new elite class in what we now plainly see were, to it, unimaginable ways.

The elite’s current obsession, and rightfully so from the standpoint of survival, is to recapture technology and bend it once again to the pursuit of their dreams and, more fundamentally, the protection of their answer to the “why bother” question. But the problem is, as reports from the latest gathering at Davos make plain, they know their approach, no matter what their degree of passion or skill, is failing. Over the twenty-odd years of the past pre-digital generation, the elite’s social compact succeeded in persuading Americans that the progressive perfection of society was why to bother struggling to make life worth living. Now, today’s digital conditions mercilessly reveal how prosperity has retreated and possibilities have contracted for those outside the Davos Elysium—the despairing, underemployed father in the MAGA interior no less than the depressed, overworked daughter in the MeToo metropolis. The social compact forged by the fusion of the pre-digital establishment and counterculture now rings hollow. Increasingly it feels not just rigged but, even worse, fake—unreal, and deadly in its unreality.

This is not a reckoning the elite has any desire to confront, much less to broadcast. What is broadcast is the experience and imagination of those individuals who still believe, who know and proclaim their very real empowerment stake in advancing and intensifying the social justice compact—even as so many of them spiral downward into smaller, less purposeful, less enduring, and in many cases more personally despairing and narcotized lives. Lives less recognizably and worthily human.

Digital technology is partly responsible for this paradox, which, to a degree, adds new fuel to the crisis-stricken social justice regime. As it turns out, the more the human person is reduced in stature and significance, the harder it becomes to make it through the day, and the greater the appeal of surrendering all why-bother questions to the image of the perfect society as the justification of last resort. To the degree digital technology is disenchanting away the old answers of the past twenty-five years—to become rich, famous, to party, to be glamorous, to be cool, to be popular, to have fun, to dream big, to have it all—digital is breathing new life into what were “supposed to” be obsolete (socialist) iterations of the social justice script.

But to an even greater degree, the rise of digital technology has revealed to the unironic and un-vengeful Americans wondering why to bother that the whole regime model of the post-industrial age no longer functions as a viable, much less just, social compact. The dream of becoming a member of that regime’s elite is shattering—across the great post-industrial ruling class industries of journalism, academia, civil service, entertainment, communications, advertising, and on and on. The labor of life in the service of social perfection—and the elite and victim classes instrumental to its advancement—is no longer worth the trouble, either at the level of reality or of imagination.

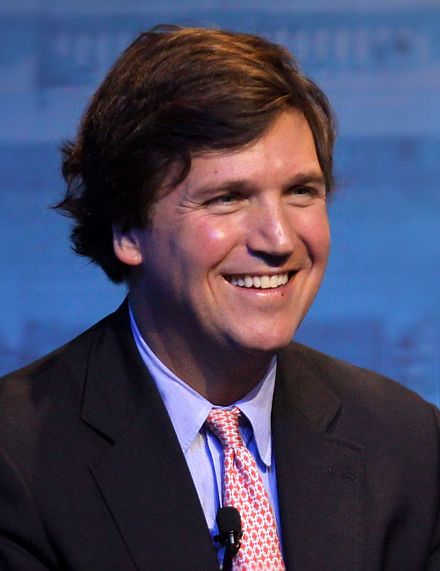

Something must flow into this vacuum, and, again, it is something ostensibly obsolete, which the elite’s imagineers utterly failed to imagine returning. The sudden impact of January’s viral monologue by Tucker Carlson shows clearly what that something is: a restored social compact where the state is the guarantor of the nation, in service of a much different kind of architecture of exertion and protection than the imagineering that ruled the post-industrial social justice regime.

“What kind of country do you want to live in?” Carlson asks. “A fair country. A decent country. A cohesive country. A country whose leaders don’t accelerate the forces of change purely for their own profit and amusement,” and, “above all, a country where normal people with an average education who grew up in no place special can get married, and have happy kids, and repeat unto the generations.”

In Carlson’s monologue, the implicit answers to the question of why to bother enduring life’s pain and struggle fuse pride and humility in more enduring ways than the redistributors of empowerment can supply. “We do not exist to serve markets. Just the opposite. Any economic system that weakens and destroys families is not worth having. A system like that is the enemy of a healthy society.” Carlson echoes the growing response to the digital age by tracking a deep public shift from a redistributivist ethic to a distributist one, where the goods adequate to secure roles of integrity in the cycle of human life are broadly, not narrowly held, as a matter of common right, not special privilege. This turn, from an ethic of redistribution back to an ethic of distribution, retrieves what seemed to our elites an obsolete form of nationalism in a newly real and experiential way.

Obviously, one consequence of a shift this profound is a raft of new challenges. In no cultural framework is the problem of justice ever “solved.” But the post-industrial project to replace traditional cultural claims to ultimate meaning with the political dream of perfecting universal social justice created a problem it could not solve. Too many Americans will refuse to suffer—increasingly isolated, alone, interchangeable, and anesthetized—for such a dream. This is why we are now in the world our elite could not imagine: one in which they have no reason to bother.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Carlson's provocations are captivating, but his solutions can't capture the center.

The American Founders and Lincoln knew what Tucker Carlson's critics do not: American Government exists to help Americans.

Reflections on the monologue that rocked the Right.