Does Curtis Yarvin understand Aesthetics?

Resurrection Aesthetic

In our end is our beginning.

Every beautiful thing is a gift for always. God, give us beauty again. We lost her somewhere in the muck and acid crater pools out past the Somme. But spring flowers bloom again in the fields of France, and this is an exhortation. Write new poetry for a new age. Look in the past and find the Muse is only waiting to be found.

What we call the beginning is often the end

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

The end is where we start from.

– T.S. Eliot, “Little Gidding” V

The latter half of last century recognized something died, an owl flew, the modern age ended. Post-modernism trilled the funereal bugles well, played Taps for all to hear. But to build a future it is not enough to dismantle ruins. The masonry, once torn down, must be used as stones for stronger columns and higher arches.

Neoliberalism, neoconservatism, neomarxist social democracy kept remnants of a post-catastrophe order shuffling along, with pickled bits of the past like specimens in formaldehyde. It hid the rotting smells behind technological progress, behind triumph over Communism, behind men on the moon.

But the order built by the undead crumbles around our ears. It is time to recognize its dissolution. It is time to look for something truly new, alive, and beautiful.

A people without history

Is not redeemed from time, for history is a pattern

Of timeless moments.

– “Little Gidding” V

The French intellectual Rémi Brague says the West is defined by its “Romanity.” The theorists of the last century spoke much of Athens and Jerusalem, but transmission was not direct. It was the Roman virtue of “secondarity,” of taking shamelessly from what had been before, of making the world Roman, that sent the mouldering towers around us heavenward in the first place.

The Romans were shameless borrowers not because they were indifferent but because they were judicious. They ate and digested, adopted and reared, embraced and loved the past, the cultures they encountered, the peoples they made Roman.

Christianity did the same and more. Grafted as a branch to root into the covenant with Abraham, it took up an older testament to undergird its gospel, set up a universal tabernacle, and welcomed the nations to a heavenly city. Frankish tribesmen established a Holy Roman Empire. This new secondarity, with its desire to break bread with all, to share a cup, to hear and tell stories at the foot of the cross, was baptized Greek xenia, the hospitality of Alcinous the Phaeacian for Odysseus.

And what there is to conquer

By strength and submission, has already been discovered

Once or twice, or several times, by men whom one cannot hope

To emulate—but there is no competition—

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.

– “East Coker” V

Plato, as Heidegger reminds us, said poesis is a bringing forth, and that physis, too, is a kind of poesis. What is being brought forth today, and from where? What should we bring forth again?

Only the fullness of the human person from where it lies buried beneath technicity, uncovered in the act of expression and in what is expressed.

Epics taught ancient peoples the ways of gods and men. Tolkien knew this. Austen wrote of men and women finding virtue in their place. Middlemarch mourned the loss of this innocence. Wilde made an art out of roleplay as he sought a role in society. Wallace and Houellebecq see us reduced, addicts: corporate drones, consumer pigs, bureaucrats.

We are not born tabula rasa but we are born, and must be cared for and shown the way to live. Do not let the jingle of the advertizer echo in gray recesses where poetry could sing. Let it be a call to take up arms, to take up your cross. The modernists wrote dirges for the dead. Write lyrics for the living.

Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind

Cannot bear very much reality.

Time past and time future

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

– “Burnt Norton” I

——

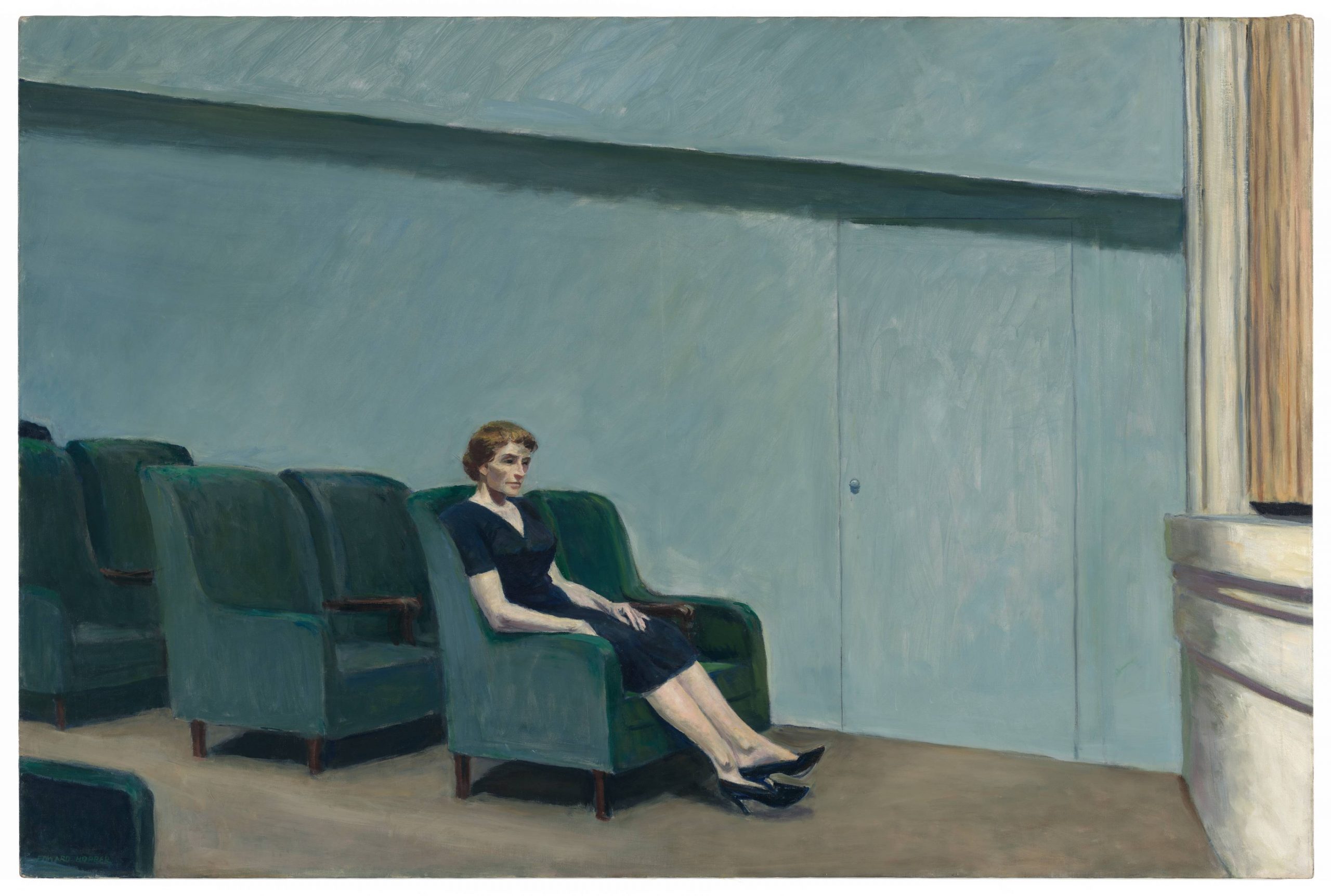

Art gave up on God long ago; more recently, it has given up on the world.

The “Self,” that shadowy, evasive object of introspection, stands as the great protagonist of 21st Century letters. Where earlier generations knew that the daily activities of human life admitted of a gratuitousness that entangled our doings with an unseen something beyond the chaotic and finite human world—an architect’s flourish on a cornice, a poet’s careful description of a landscape, the farmer’s careful fashioning of an axe-handle—our age understands our various doings to be concerned only with assembling and disclosing this Self.

Talking about God or the gods, our age insists, is for uncultured, sentimental rubes. At best, a work of art can teach us what the artist thought about divinity, or maybe how the artist participated in the theological discourse of whatever historical milieu they inhabited. Strive as we might to articulate an artistic experience in a religious register, our words are just hot air.

All things are a flowing,

Sage Heraclitus says;

But a tawdry cheapness

Shall reign throughout our days.

– Ezra Pound, “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley” 1.III

It is good, then, to counter the cultural momentum toward disenchantment with a vision of art as something that can inspire, that can (as the Latin suggests) fill one again with breath.

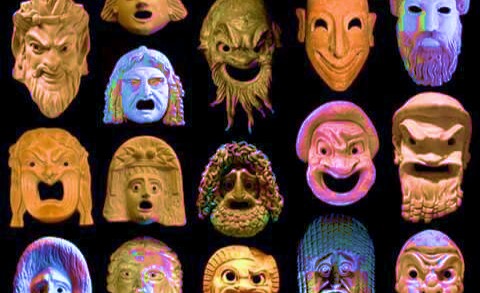

The age demanded an image

Of its accelerated grimace,

Something for the modern stage,

Not, at any rate, an Attic grace;

Not, not certainly, the obscure reveries

Of the inward gaze;

Better mendacities

Than the classics in paraphrase!

– “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley” 1.II

In the early 1900s, facing a leaden age not much different from our own, a 30-year-old Ezra Pound began work on what would unfold over the next 50 years into the monumental collection of the Cantos. He continued this work through exile, imprisonment, and institutionalization in St. Elizabeth’s psychiatric hospital; it followed him, unfinished, to his grave.

Assembled from artefacts from an enormous breadth of the human enterprise—the mythological deposits of Greece and Rome, poetry and philosophy from ancient China, economic and artistic discourses from Renaissance Italy, Edwardian lyric—Pound’s poem is a confounding assemblage of observations and references, built as one might make a temple: something one must walk into, live inside of, and in which the whole can only be understood by paying close and careful attention to the parts, themselves graspable only in light of the whole. Poems, Pound demonstrates, are like buildings: they must be made carefully.

There died a myriad

And of the best, among them,

For an old bitch gone in the teeth,

For a botched civilization,

Charm, smiling at the good mout

For two gross of broken statues,

For a few thousand battered books.

– “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley” 1.V

Guy Davenport, one Pound’s greatest interpreters, says the Cantos are about “the tragic loss of sensibility by which men live well.” This is its center, but not its entire circumference. Even the most superficial read of Canto LXV—the infamous “Usura Canto”—reveals an exhortative character beyond this concern for sense:

with usura, sin against nature,

is thy bread ever more of stale rags

is thy bread dry as paper,

with no mountain wheat, no strong flour

with usura the line grows thick

with usura is no clear demarcation

and no man can find site for his dwelling.

This is not simply an idle beauty meant for enjoyment: Pound is not simply trying to get us to see, but rather trying to get us to see something. Beyond the verb lies the noun—beyond the inspiring lies the object of inspiration.

Go, my songs, seek your praise from the young and from the intolerant,

Move among the lovers of perfection alone.

Seek ever to stand in the hard Sophoclean light

And take your wounds from it gladly.

– “Xenia” VI

The world is formed by our attention. (Charles Olson: “When the attentions change / the jungle leaps in / even the stones are split…”) How we perceive determines in large part what we perceive, and what we perceive determines what we make.

The restoration of the world demands we turn away from punditry and back to poetry: from the heavens of abstraction to the quotidian surroundings in which we conduct our day-to-day affairs. Here, if we’ve learned to see, we will find everything old made anew. And then we can begin again.

——

And the wisdom of age? Had they deceived us

Or deceived themselves, the quiet-voiced elders,

Bequeathing us merely a receipt for deceit?

The serenity only a deliberate hebetude,

The wisdom only the knowledge of dead secrets

Useless in the darkness into which they peered

Or from which they turned their eyes. There is, it seems to us,

At best, only a limited value

In the knowledge derived from experience.

– “East Coker” II

The Renaissance marked a second wind of secondarity, classical magnanimity rediscovered by a humble people, close to the earth, aware of a suffering God. Teetering on the edge of an era, living amid the dying light of the Medieval world as the sun of modernity began to rise, they dug deep into the deposit of European history and exhumed the spirit of a forgotten age.

The resultant alchemy brought forth a wealth of forms half borrowed, half new: perspective, proportion, chiaroscuro, realism. This meeting of old and new produced a way of seeing: a sense of the perpetual fragility of humankind—a frightened, doomed animal, adrift in a hostile and chaotic cosmos—borrowed from Athenian tragedy, but wedded to the salvific optimism of the Christian Gospel.

We too live on a cusp between ages, between the faded modern world and whatever lies ahead. Let us develop the courage to imitate the humility of those who came before us. Let us recover the shameless dignity that will allow us to see clearly.

You are not here to verify,

Instruct yourself, or inform curiosity

Or carry report. You are here to kneel

Where prayer has been valid. And prayer is more

Than an order of words, the conscious occupation

Of the praying mind, or the sound of the voice praying.

– “Little Gidding” I

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Now more than ever, there is no way to solve the problem of men.

A city of heaven returns to our barren earth.

New artifacts overthrow old impostures.

America’s aesthetic movements must resist commodification.