In our end is our beginning.

The Deep State vs. The Deep Right

New artifacts overthrow old impostures.

Under any stable regime in any time or place, from 19th-century Petersburg to 21st-century D.C., it will be found that the general population has no effective procedure, legal or illegal, by which to either control or replace the central organs of the state.

This is normal and not weird. Autocracy is a human universal. Apparent exceptions to universals suggest sensor malfunction.

The 19th-century Russian intelligentsia could at least dream of hurling bombs at the Czar. The modern administrative state, no less autocratic, is quite czarless. It is an oligarchy, not a monarchy. It has no one who can be effectively bombed.

Final decision-making authority must exist somewhere within its Borgesian labyrinth of process. But for all practical revolutionary purposes, the “deep state” is as decentralized as Bitcoin, and as invulnerable—to ballots and bullets alike.

It does not always get its way immediately. Politics can still frustrate it. Violence can make it angry. No force that can objectively capture, damage, even sustainably resist it exists. Again: this is historically normal, not historically weird.

In a healthy regime, military resistance is insane and political resistance is useless. And anyone who thinks early 21st-century Washington is an unstable or dying regime should pray on their knees to never experience such a thing for real.

Yet there is a third dimension of revolution: art. Art is the domain of the deep right—or art–right. You may not have noticed this kraken. It has noticed you.

Alas, populists have been here before us, and soiled the place. “Politics is downstream from culture.” If culture involves wooing the masses with ham-handed propaganda—the ’30s “proletarian novel” of the Daily Worker, repeated as farce—we must quietly excuse ourselves.

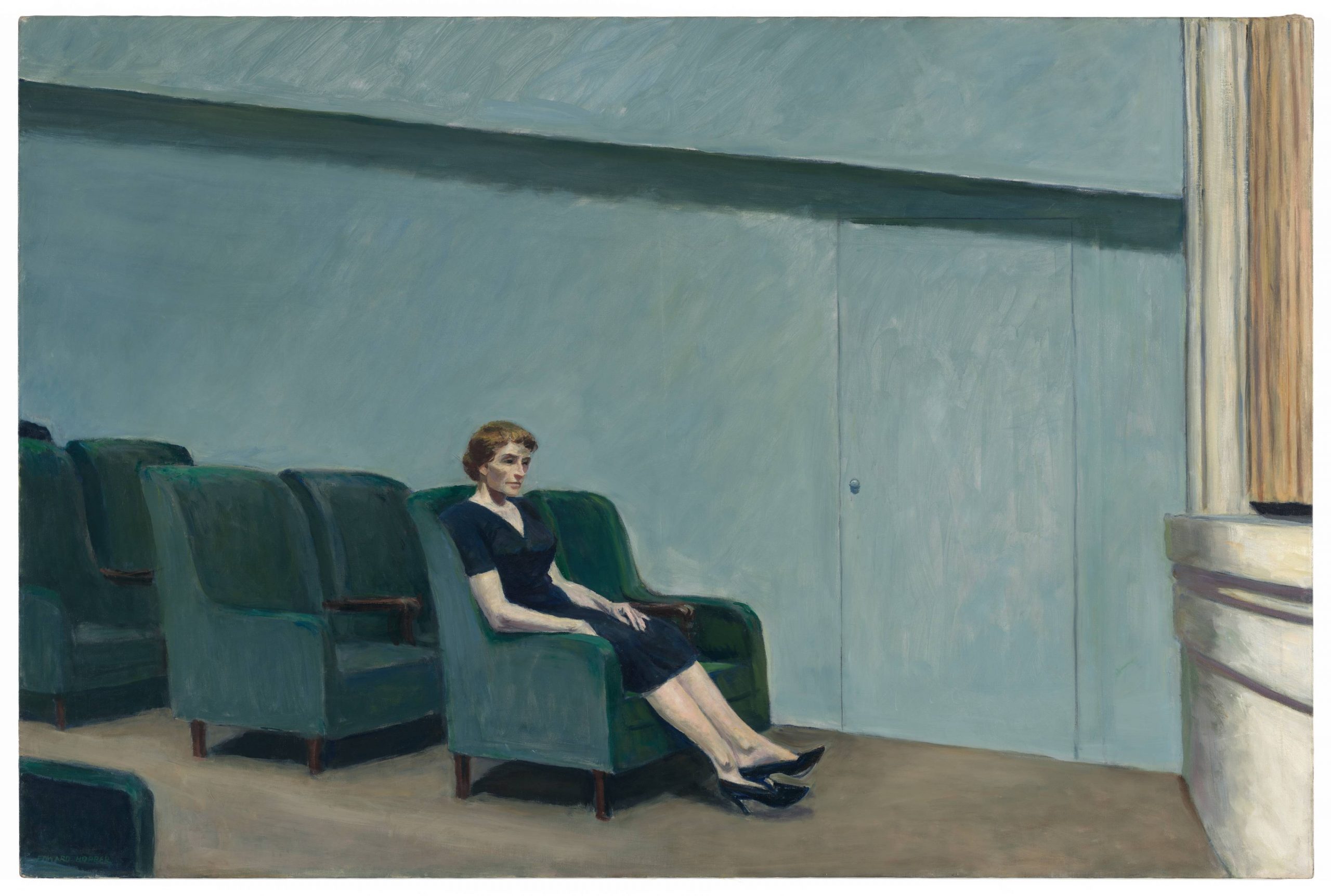

Art, if it’s art at all, aims at supreme aesthetic excellence. It does not even deign to notice its audience. If the whole world is inferior to art, art doesn’t give a rat’s ass. Art is not competing with anything but itself, the past, and the future. If it is not sub specie aeternitatis, it is not art.

Art as Weapon

But how can art become a weapon? Oh, art is extremely dangerous. Anything dangerous is a weapon. Let’s look at how, in the last century, one aesthetic killed hundreds of millions of people.

Czarist Russia, which the 19th-century intellectual world considered the epitome of cruel autocratic despotism, also produced some of that century’s best novels. Its writers, a few nuts like Dostoyevsky excepted, were not supporters of the Czar. Ideologically, they tended to be fashion victims of London—a pretty normal thing in that century.

(Tolstoy is perhaps the great figure of this generation. Tolstoy himself, of course, would not hurt a fly.)

This disaffected intelligentsia eventually became so culturally dominant that they managed to buffalo the Czar into helping the British and French start their great war to make the world safe for democracy. This had great results for everyone—including, of course, the Czar. At least it wasn’t boring.

The ultimate cause of the entire Russian Revolution—February and October—was Tolstoyan anglophilia, an aesthetic impulse. The prophet of October was of course Marx—a born-again London gentleman, whose ideas are drivel and whose writing is divine.

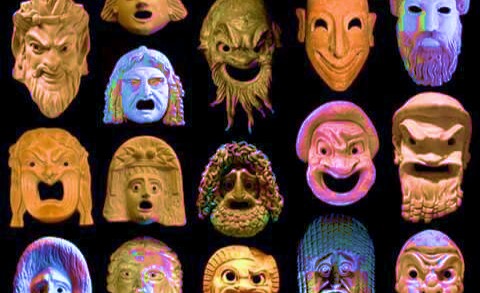

Bolshevism was an aesthetic experience. Nazism was also an aesthetic experience. And democracy remains one. To play in this league, to compete on this historical scale, requires aesthetic gestures of great power: strong gods.

From a more mundane perspective, Pareto defined a revolution as a “circulation of elites.” A new elite, with new personnel, new doctrines and new institutions, displaces the old. Art is the language of the elite: the language of talent. Elites have been defining themselves with art for three hundred centuries.

All revolutions begin as a fundamentally aesthetic break. The first step in a cultural revolution is the birth of a new artistic school. Behind this aesthetic must come an artistic movement, then artistic institutions. These institutions, if they prosper, become the cultural core of the new regime. Art is the spring, lever and hinge of any real change in our time.

Artistic dominance is not a marketing metric. Power is not a function of book sales. Power is achieved when legacy elites fear the new revolutionary elites—are shamed and humbled by the sheer excellence of their work, and fear to even speak their names. Dominance always markets itself.

The easiest path to aesthetic dominance is mere truth. Above all, one feature makes any story ugly: lies. Most regimes are destroyed by their own accumulated mendacity, which renders them ugly, and undermines the aesthetic foundations of their support.

Once regimes begin to rely on force to reinforce their narrative, they are unlikely to ever be able to return to a freestanding story, which people just believe because it seems obviously true.

In the short run, lies can work wonders. In the long run they tend to show. Lies are also very hard to get rid of, even when no longer useful. They are normally burned off en masse, by the next unconditional sovereign discontinuity (regime change).

Every new regime sees its predecessor as profoundly mendacious. Few are wrong. As Carlyle said of the Revolutions of 1848:

It is probably the hugest disclosure of falsity in human things that was ever at one time made. These reverend Dignitaries that sat amid their far-shining symbols and long-sounding long-admitted professions, were mere Impostors, then? Not a true thing they were doing, but a false thing. The story they told men was a cunningly-devised fable; the gospels they preached to them were not an account of man’s real position in this world, but an incoherent fabrication, of dead ghosts and unborn shadows, of traditions, cants, indolences, cowardices,—a falsity of falsities, which at last ceases to stick together. Wilfully and against their will, these high units of mankind were cheats, then; and the low millions who believed in them were dupes,—a kind of inverse cheats, too, or they would not have believed in them so long. A universal Bankruptcy of Imposture; that may be the brief definition of it.

All institutions become infected with the same impostures. Thus all institutions become ugly. Where those institutions produce art, that art must contain and reinforce all these mendacities. The art itself becomes literally ugly—we have all seen it.

We are trained to look past these ugly lies. They are blemishes, we think, on a better world. Art and art alone—not rational argument—can hold our hands as we step outside them. What is art? Are “memes”—all the rage with my fellow kids!—art?

Certainly any age has its idols. Once enough clay feet are spotted among the idols, all the idols will fall into contempt; and all will be mocked, among my fellow kids, with no regard at all for truth or falsity. Clearly this is where we are now.

The Washington Post just ran a great op-ed by a woman who caught her tween kid laughing at a Hitler meme. Hitler is looking behind him, bored, at some Party rally. A MAGA-hat bro leans forward in a quote bubble, and—tips him off about Normandy.

Somehow this child convinced his mom that he’d misinterpreted the meme and laughed because it was actually making fun of Hitler. More diversity training was still indicated—and, we are told, effective. God bless the young.

But as the Bible says: when I became a man, I put aside childish things. These memes, these little japes, toys for a tween to mock his middle-aged mom, are not the planes, tanks and battleships of the artistic struggle for the world. When the lion hunts his cubs must retreat.

New Aesthetics, New World

Here is needed not some ghost of the old century, but the absence of that century; not the absence of the old, but a vision of the new; not a new vision, but a new institution; not an institution, but a new academy; not an academy, but a new regime; not a regime, but a whole world renewed.

Friends, I say to you: we are not even at the beginning of the beginning. Our first step, now and for quite some time, is one thing and one thing only: creating the finest possible art.

The first step in getting to the 21st century is inventing it. The first step in inventing the 21st century is an aesthetic vision so strong, true and clear that it dominates and intimidates the stale old aesthetics of the 20th century.

Man invented art for one reason: to mog. The only reliable way to change a regime is to impress it into surrendering of its own free will. Persuasion is beta; only the uncertain persuade. The strong perform.

Art, in the broadest possible sense—some might say content—is the bloodless weapon that can replace the world. The world cannot be won by force. She must be seduced by greatness. And while the great will never lack followers, counting followers never brought greatness to anyone.

Apart perhaps from Houellebecq, Bronze Age Pervert is the first major writer in our time to understand and inhabit this reality. Of course, that doesn’t mean we need his foam in our cappuccino. Indeed, when the future looks back, Bronze Age Mindset will be seen as an early, badly edited and produced, slightly embarrassing effort—notable for when, not what. Yet the Pervert himself may be best positioned to surpass his early work.

(In fact such a book, a book of true power, should not be a crappy POD edition, available to any digital idiot, but a limited calfskin printing, sold by invitation only. Everything about both experience and object must be unique, amazing, and intimidating: a book, like its author, must thrive.)

Yet the mission of the work is simple. Many misunderstand the message: they see BAP make a positive case for this thing, that thing, some crazy thing; Hollow Earth, Fomenko chronology, genetic inferiority of Udmurt and other Finnic peoples… wake up! BAP has no “message” in this stupid sense.

Like his ancestor Nietzsche, BAP is not “for” this, that, the other thing. His book is not a lecture but a fire. It does not teach, it burns; it is not words, but an act.

And it has no message. But it does have a theme. The theme of Bronze Age Mindset is the smallness of the modern world—in mind, in space, in time.

To others, righteous among the normies, it is given to push back on the shrinking walls of the Overton bubble. Nothing wrong with that; but the real mission is to escape the bubble.

The ocean is much larger than its surface. Most of it is an empty desert. As a mass of meat, a mere human army, the deep right is tiny.

Yet as a space—artistic, philosophical, literary, historical, even sometimes scientific—all fields that are ultimately arts—the deep right is much larger than the mainstream.

If we compare just the books published in 1919, to those published in 2019, we see a far wider range of perspectives. Almost all present ideas are also found in the past; but almost all ideas found in the past have vanished. Like languages, human traditions are disappearing—and a tradition is much easier to extinguish than a language.

The mainstream mind looks at its own bubble through a fisheye lens. The bubble is almost everything. All of outer space, all of history, is a tiny black fringe around it. This fringe is, of course, completely uninhabitable.

Yet in an even lens, the past is much bigger than the present. The deep right operates in deep history; it accepts no temporal or geographic boundaries. It thinks, with Ranke: all eras stand equal before God.

And if all eras are equal, so then are their ideas. Until we accept the prerevolutionary world, the old regime before this old regime, as valid and legitimate, we are not yet in contact with the true vastness of free intellectual space.

The theme of Bronze Age Mindset is that if you think your mind is broad and open, you are wrong. It is a tiny, hard lump, like a baby oyster—closed hard as cement by nothing but fear. “And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom.”

This message cannot be said. It must be shown—performed. And the only way to show it is for one author, a character yet more than a character, to display mastery of that space—the whole immense space of mind and time and space outside our increasingly absurd little “mainstream” bubble.

In time this will no longer be enough. In time, every no will have been said. A yes will be required. To escape is not just to escape, but, in the end, to build.

But every beginning belongs to itself. Now anyone can look out, outside the bubble, to see a fire burning in deep space, where nothing can live and no fire should be. And that, for today, is more than enough.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Does Curtis Yarvin understand Aesthetics?

Now more than ever, there is no way to solve the problem of men.

A city of heaven returns to our barren earth.

America’s aesthetic movements must resist commodification.