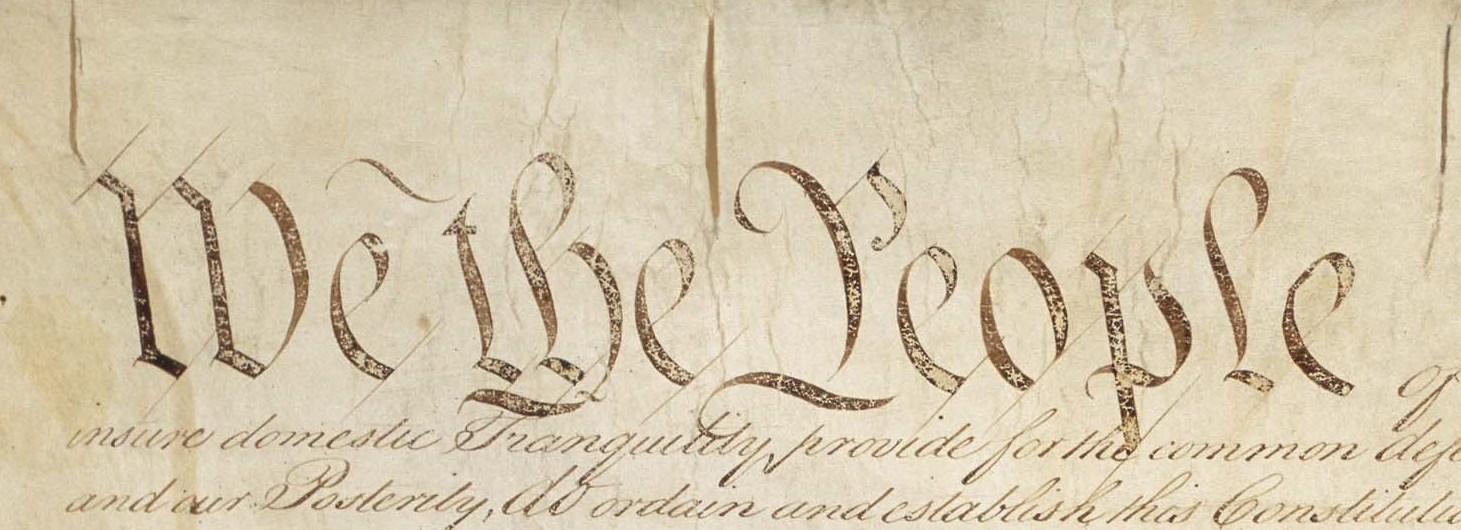

Birthright citizenship should be an uncontroversial right.

The Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment: the Congressional Debate

A reply to Professor John Yoo's and Judge James Ho's case for the original understanding of the 14th Amendment.

Professor John Yoo, along with many others, has argued that I am wrong about my interpretation of the 14th Amendment. Yoo’s argument is similar to Judge James Ho’s case for the original understanding of the 14th Amendment. I address them specifically because they make much more serious arguments than most others who should know better. In what follows, I address misconceptions about the original understanding of the 14th Amendment drawn from the Congressional debates, particularly about what it means to be “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States. In future articles, I will address the question of whether citizenship in the 14th Amendment was based on the English common law, and whether the repeal of birthright citizenship will occasion a second Dred Scott decision as Judge Ho has tendentiously claimed; finally, I will argue how the majority opinion in Wong Kim Ark was wrongly decided and should be repealed.

Who is “subject to the jurisdiction”?

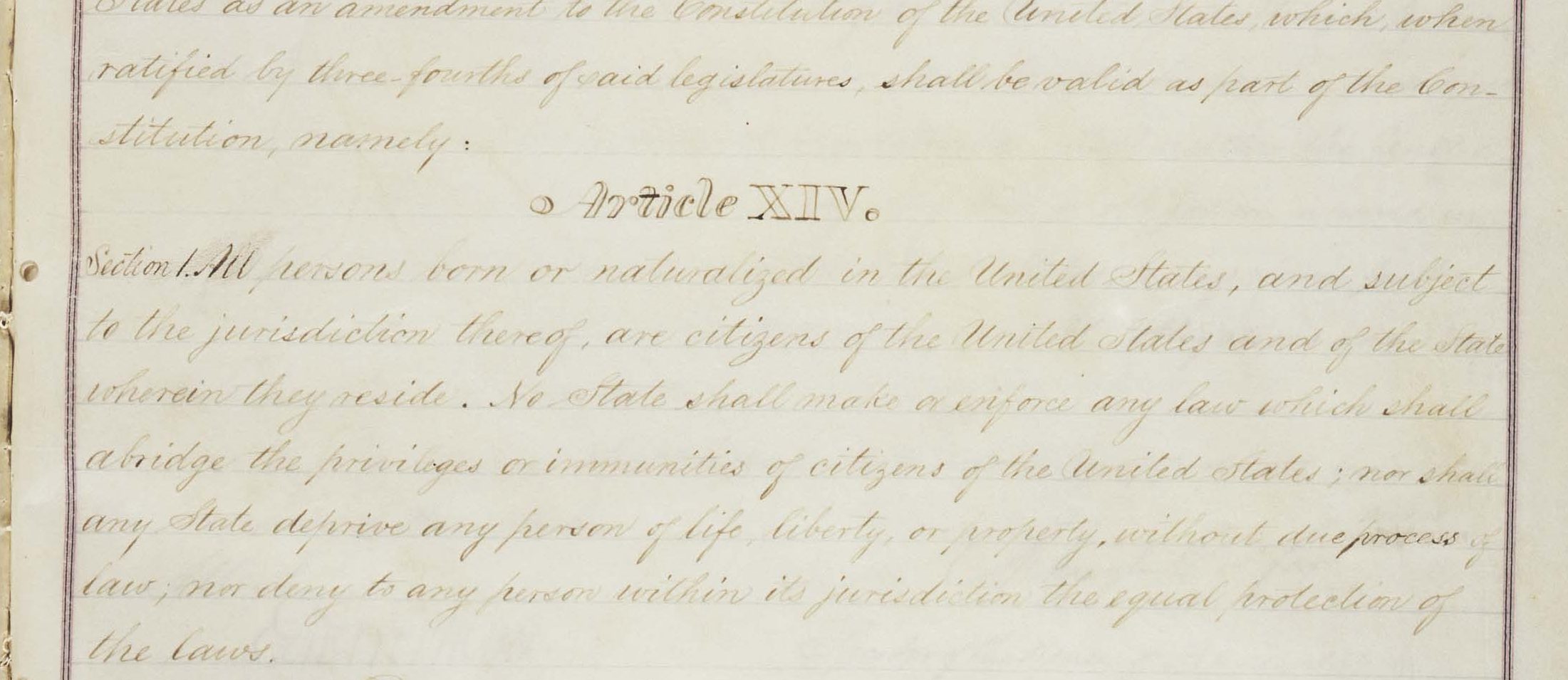

The Citizenship Clause was added late in the debate over the 14th Amendment. Senator Benjamin Wade, Republican of Ohio, suggested on May 23, 1866 that, given the importance of section one’s guarantee of privileges or immunities to United States citizens, it was imperative that a “strong and clear” definition of citizenship be added to the proposed amendment. He suggested “persons born in the United States or naturalized by the laws thereof.”[1] Senator Howard, Republican of Michigan, responded on May 30, 1866, with a proposal that was drafted in the Joint Committee on Reconstruction and eventually became the first sentence of the 14th Amendment as finally adopted. It read: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the States wherein they reside.”[2] Howard was the floor manager for the Amendment in the Senate, and evidently he and the Joint Committee placed some importance on the addition of the jurisdiction clause, which meant, at a minimum, that not all persons born in the United States were automatically citizens, but also had to be subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.

Howard’s remarks introducing the new language in the Senate have attracted much attention—and much controversy. “I do not propose to say anything on that subject,” Howard said,

“except that the question of citizenship has been so fully discussed in this body as not to need any further elucidation, in my opinion. This amendment which I have offered is simply declaratory of what I regard as the law of the land already, that every person born within the limits of the of the United States, and subject to their jurisdiction, is by virtue of natural law and national law a citizen of the United States. This will not, of course, include persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers accredited to the Government of the United States, but will include every other class of persons. It settles the great question of citizenship and removes all doubt as to what persons are or are not citizens of the United States. This has long been a great desideratum in the jurisprudence and legislation of this country.”[3]

Ideological liberals (and conservatives such as Professor Yoo and Judge Ho) have in recent years invented a novel and fabulous interpretation of this passage, maintaining that when Howard mentions that “foreigners, aliens” are not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States he means to include only “families of ambassadors or foreign ministers.” If so, this would be an extraordinarily loose way of speaking: ambassadors and foreign ministers are foreigners and aliens, and thus their designation as such would be superfluous.

If we give full weight to the commas after “foreigners” and after “aliens,” this would indicate a series which might be read in this way: “foreigners, aliens, families of ambassadors, foreign ministers,” are all separate classes of persons excluded from jurisdiction. Or it could be read in this way: “foreigners, aliens, [that is, those who belong to the] families of ambassadors or foreign ministers.” I suggest that the natural reading of the passage is the former, i.e., that the commas suggest a discrete listing of separate classes of persons excluded from jurisdiction. Of course, the debate was taken by shorthand reporters and not always checked by the speakers, so the issue cannot be settled simply on the basis of the placement of commas.

In addition, Howard seemed to make a glaring omission—he failed to mention Indians as being excluded from the jurisdiction of the United States. He was forced to clarify his omission when challenged by Senator James R. Doolittle of Wisconsin, who queried whether the “Senator from Michigan does not intend by this amendment to include the Indians;” Doolittle thereupon proposed to add the language of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 “excluding Indians not taxed.” Howard vigorously opposed the amendment, remarking that “Indians born within the limits of the United States and who maintain their tribal relations, are not in the sense of this amendment, born subject to the jurisdiction of the United States. They are regarded, and always have been in our legislation and jurisprudence, as being quasi foreign nations.”[4] In other words, the omission of Indians from the exceptions to the jurisdiction clause was intentional. Howard clearly regarded Indians as “foreigners, aliens” and thus not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States. This conclusion was supported by Senator Lyman Trumbull who, as we will discuss below, also opposed Doolittle’s amendment. This is clear evidence against the claims of ideological liberals and others that Howard meant that foreigners and aliens included only the families of ambassadors and foreign ministers. But there is much more evidence available to those who read the legislative history closely.

Senator Howard declared quite clearly that “[t]his amendment which I have offered is simply declaratory of what I regard as the law of the land already.” The “law of the land” to which Howard referred was undoubtedly the Civil Rights Act of 1866, passed over the veto of President Andrew Johnson by a two-thirds majority in both houses less than two months prior to the May 30th debate in the Senate. The Civil Rights Act provided the first definition of citizenship after the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, specifying that “[t]hat all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States.” Thus an overwhelming majority of Congress on the eve of the debate over the meaning of the Citizenship Clause of section one of the 14th Amendment were committed to the view that foreigners (and aliens) were not subject to birthright citizenship. Many statements in the debate made by supporters of the Citizenship Clause support this conclusion.

Jurisdiction was understood in terms of allegiance

Representative John M. Broomall, Republican of Pennsylvania, asked this rhetorical question: “What is a citizen but a human being who by reason of his being born within the jurisdiction of a Government owes allegiance to that Government?” The same sentiment was expressed by Representative M. Russell Thayer when he stated that “[a]ccording to my apprehension, every man born in the United States, and not owing allegiance to a foreign Power, is a citizen of the United States.” Representative John Bingham of Ohio in the Civil Rights Act debate also spoke of jurisdiction in terms of “allegiance.” He averred that the introductory clause of the act “is simply declaratory of what is written in the Constitution, that every human being born within the jurisdiction of the United States of parents not owing allegiance to any foreign sovereignty is . . . a natural-born citizen,” later refining his statement to not “owing foreign allegiance.”[5] Thus, foreigners (and aliens) were those not within the jurisdiction of the United States because they owed allegiance to foreign governments, and thus could not owe allegiance to the United States, a prerequisite for being “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States. There is no evidence anywhere in the debates to support the tortured conclusion of ideological liberals that the jurisdiction clause applies only to families of ambassadors or foreign ministers.

Most of those who voted in favor of the Civil Rights Act were still serving in Congress when the 14th Amendment was under consideration. In fact, Senator Lyman Trumbull, the author of the Civil Rights Act and Chairman of the powerful Senate Judiciary Committee, was an ardent supporter of Howard’s version of the Citizenship Clause. “The provision is, that ‘all persons born in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens.’ That means ‘subject to the complete jurisdiction thereof.’ . . . What do we mean by ‘subject to the jurisdiction of the United States?’ Not owing allegiance to anybody else.” In other words, citizenship applied to those parents who did not owe allegiance to anybody else, were subject to the complete jurisdiction of the United States, and not subject to a foreign power.[6]

After much vigorous debate about Senator Doolittle’s proposed amendment, Senator Howard entered the fray once again supporting Senator Trumbull’s statement about jurisdiction:

I concur entirely with the honorable Senator from Illinois…. Certainly, gentlemen cannot contend that an Indian belonging to a tribe, although born within the limits of a State, is subject to the full and complete jurisdiction. That question has long since been adjudicated, so far as the usage of the Government is concerned. The Government of the United States have always regarded and treated the Indian tribes within our limits as foreign Powers.[7]

As we have seen, the Civil Rights Act had excluded “Indians not taxed” from birthright citizenship. As we have also seen, both Howard and Trumbull opposed the addition of this language to the 14th Amendment. Thus the Citizenship Clause, by its exclusion of “Indians not taxed,” was not simply a restatement of the law as it already existed. In fact, the exclusion of Indians was inherent in the jurisdiction clause itself and did not need to be stated explicitly. Indians, Trumbull argued, owed allegiance to their tribes, not the United States, and thus were not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States.

Foreigners and aliens similarly owed allegiance to other governments. Some of them might be mere sojourners, who even though subject to the laws and to the courts, are not subject to the jurisdiction of the United States. Illegal aliens are present in the United States and subject to our laws and courts, but their presence doesn’t make them “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States because they owe allegiance to another government and thus are not subject to “the complete jurisdiction of the United States.

In the light of the debate over the Civil Rights Act, can there be any real dispute that “foreigners, aliens” in Senator Howard’s opening statement does not refer exclusively to “families of ambassadors or foreign ministers” but to “foreigners, aliens” as a separate class? Thus, it is fair—and accurate—to read Howard’s statement introducing the Citizenship Clause to the Senate in this way:

“This amendment which I have offered is simply declaratory of what I regard as the law of the land already, that every person born within the limits of the United States, and subject to their jurisdiction, is by virtue of natural law and national law a citizen of the United States. This will not, of course, include persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens [or] who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers accredited to the Government of the United States, but will include every other class of persons.”

This use of the bracketed “[or]” is fully justified when this statement is read in the light of the Civil Rights Act, which explicitly excludes foreigners from birthright citizenship, an exclusion that was approved by an overwhelming majority of the same Congress that approved the Citizenship Clause of the 14th Amendment.[8]

The numerous citations I have made to the use of “allegiance” by Senators Howard and Trumbull and Representative Bingham (and there are many other citations I could offer) as the principal factor in determining “jurisdiction” should invalidate Judge Ho’s allegation that “allegiance” occurs only in “stray references.”[9] Professor Yoo and Judge Ho might legitimately ask why the framers of the Citizenship Clause didn’t write “subject to the allegiance of the United States,” if, as Senators Howard and Trumbull (and many others) seem to argue, that is what “subject to the jurisdiction” meant? That question is never broached in the 14th Amendment debates, but it is not difficult to determine why Howard and Trumbull supported the language they did. “Allegiance” is a term of art under the English common law. Birthright subjectship under the English common law (citizen or citizenship is never mentioned in Blackstone) is the debt of gratitude that a subject owes to the king in return for being born within his protection. This debt entails “perpetual allegiance” which cannot be cancelled or thrown off in any way without the permission of the king. Perpetual allegiance is the obligation of birthright subjectship. There is credible evidence from the debates over the Civil Rights Act of 1866 that its author, Senator Trumbull, specifically intended to avoid common law language when dealing with United States citizenship. Trumbull remarked that his goal in the legislation was:

“To make citizens of everybody born in the United States who owe allegiance to the United States. We cannot make a citizen of the child of a foreign minister who is temporarily residing here. There is a difficulty in framing the amendment [to the act] so as to make citizens of all the people born in the United States and who owe allegiance to it. I thought that might be the best form in which to put the amendment at one time, ‘That all persons born in the United Sates and owing allegiance thereto are hereby declared to be citizens;’ but upon investigation it was found that a sort of allegiance was due to the country from persons temporarily resident in it whom we could have no right to make citizens, and that that form would not answer.”[10]

Trumbull here alludes to the fact that under the English common law temporary allegiance is “such as is due from an alien or stranger born, for so long time as he continues within the king’s dominion and protection: and it ceases, the instant such stranger transfers himself from this kingdom to another.”[11] Trumbull excludes from the citizenship clause of the Civil Rights Act aliens who, under the common law, would owe only temporary allegiance to the United States and presumably, in terms of the language of the 14th Amendment, would not be “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States, even though subject to its laws and courts. The authors of the 14th Amendment’s Citizenship Clause apparently did not want to include any notion that American citizenship was grounded in the common law, a ground that they knew was utterly inconsistent with the principles of republican government. Howard and Trumbull were tolerably clear: “subject to the jurisdiction” means complete allegiance to the United States, not temporary allegiance, or self-selected allegiance, nor allegiance that attaches by accident of birth, but only the allegiance that is established by consent. This was the social compact version of citizenship that was adopted by the framers of the Constitution and the framers of the Declaration of Independence. The Declaration explicitly rejects the common law when it announces, not only that the “just powers” of government derive from the “consent of the governed,” but that the American people are “absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown.” Under the common law “perpetual allegiance” could only be “absolved” with the permission of the king, who obviously did not put his imprimatur on the American Revolution. No one can possibly believe that the common law of “birthright subjectship” was adopted as the basis for American citizenship. It was a feudal relic that had no place in republican government. “Jurisdiction” was thus a proper republican substitute for the common law term “allegiance,” which Blackstone, as we will see in a future article, readily admitted had its origins in the feudal relation of master and servant.

The Children of Illegal Immigrants

Professor Yoo and Judge Ho rightly note that the principal purpose of the amendment was to overturn the the Dred Scott decision, but Ho claims “the amendment was drafted broadly to guarantee citizenship to virtually everyone born in the United States.”[12] Judge Ho acknowledges, however, that there are two requirements for citizenship—born or naturalized and subject to the jurisdiction. But, the Judge alleges, this means only subject to the laws and the courts, nothing more. Since everyone born in the United States is subject to its laws and courts, by Ho’s logic, they are automatically subject to the jurisdiction of the United States. His interpretation clearly renders the jurisdiction clause superfluous. Ho is, in effect, asking us to accept Senator Wade’s suggested amendment that “persons born in the United States or naturalized by the laws thereof”[13] are citizens, a suggestion that did not contain the jurisdiction requirement, rather than the one introduced by Senator Howard and the Joint Committee on Reconstruction that became part of the Constitution.

Rendering a provision of the Constitution without force and effect is the same kind of judicial activism that adds new rights to the Constitution. This is not the kind of constitutional construction we expect from someone with the legal acumen of Professor Yoo or Judge Ho. It is not enough merely to consult the latest edition of Black’s Law Dictionary under the entry “jurisdiction” to understand the framers’ meaning.[14] Their argument renders a part of the Constitution null and void.

Judge Ho contends that “no Senator disputed the meaning of the [14th] amendment with respect to alien children.” In other words, Ho claims that all agreed—even those who opposed it—that alien children were entitled to birthright citizenship. The proof, Judge Ho argues, is contained in the debate about whether the children of Gypsies and Chinese were to be accorded birthright citizenship under the Citizenship Clause. Judge Ho and others completely misread this debate. Ho is uneasy with his conclusion because, as he reports, both those against and those who argued in favor of the citizenship of Gypsies and Chinese indulged in crass, “racially charged remarks.”

Senator Edgar Cowan, Republican of Pennsylvania, was the first to bring up the issue, asking “Is the child of the Chinese immigrant in California a citizen? Is the child of a Gypsy born in Pennsylvania a citizen? If so, what rights have they?” His principal concern seems to have been that Pennsylvania would not be able to restrict the civil or political rights of those who, like the Gypsies, “acknowledge no allegiance, either to the State or to the General Government.” In a further query, Cowan asked

“is it proposed that the people of California are to remain quiescent while they are overrun by a flood of immigration of the Mongol race? Are they to be immigrated out of house and home by Chinese…. they are in possession of the country of California, and if another people of a different race, of different religion, of different manners, of different traditions, different tastes and sympathies are to come there and have the free right to locate there and settle among them, and if they have an opportunity of pouring in such an immigration as in a short time will double or treble the population California, I ask, are the people of California powerless to protect themselves?”[15]

Cowan ultimately voted against the 14th Amendment, whether for the reasons just quoted or for these reasons combined with others is not entirely clear.

Senator John Conness, Republican of California, responded to Cowan’s remarks about Chinese immigrants in California.

“The proposition before us…. relates simply…to the children begotten of Chinese parents in California, and it is proposed to declare that they shall be citizens…. I am in favor of doing so.

[T]he children of Mongolian parentage, born in California, is very small indeed, and never promises to be large…. The habits of those people, and their religion, appear to demand that they all return to their own country at some time or other, either alive or dead. There are, perhaps in California today about forty thousand Chinese—from forty to forty-five thousand…. Another feature connected with them is, that they do not bring their females to our country but in very small numbers, and rarely ever in connection with families; so that their progeny in California is very small indeed…. Indeed, it is only in exceptional cases that they have children in our State….”[16]

This was hardly a ringing endorsement for birthright citizenship for the children of Chinese living in California, since the thrust of his argument was that the question was trivial and not worth debating. He admits that the Chinese living in California did not owe allegiance and formed no attachments to the United States. They did not bring their families with them, not even their females, and they rarely reproduced, so it was safe to make them citizens. In fact, it was matter of some indifference as to whether they became citizens or not.

Cowan had argued that Gypsies owed no allegiance to the United States and states should therefore be allowed to discriminate against them in various ways as a matter of self-preservation. For him, this was a matter of States’ rights: states should be allowed to deny citizenship and thereby withhold United States citizenship from them. He appears to have been among a fairly large segment of the thirty-ninth congress who indulged the implausible hope that the Reconstruction Amendments would not change the Federal relationship.

It is important to note that neither Senator Howard or Senator Trumbull—nor anyone else—endorsed Senator Conness’ view that the Citizenship Clause would include Chinese who admittedly did not owe allegiance to the United States. His speech simply fell flat, carrying no authority whatsoever; it simply expressed one Senator’s eccentric view and was apparently not shared by any other member of the Senate. In any case, it can hardly be said to be a strong endorsement for Chinese citizenship.

Judge Ho also invokes part of the debate over the Civil Rights Act of 1866 as proof that Gypsies and Chinese were included in the Citizenship Clause of the 14th Amendment and “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States. Here too, I believe he casually misreads the debate.

Senator Trumbull was the author of the Civil Rights Act. His first version of the citizenship clause in the Act was that “All person born in the United States, and not subject any foreign Power, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States, without distinction of color.” An immediate objection was raised by Senator James Guthrie, Democrat of Kentucky that this definition would naturalize Indians. Trumbull answered that “[t]he intention is not to embrace them. If the Senator from Kentucky thinks the language would embrace them, I should have no objection to changing it so as to exclude the Indians. It is not intended to include them.”[17] Senator Cowan was quick to add, “I will ask whether it will not have the effect of naturalizing the children of Chinese and Gypsies born in this country?” Trumbull answered “Undoubtedly.”[18] Trumbull, was not, as Judge Ho thinks, signaling his intent that he wished to include Gypsies and Chinese as citizens; rather he was agreeing that if the language he proposed was wide enough to include Indians, it also wide enough to include Gypsies and Chinese. But he also agreed that the language had to be amended to exclude Indians. The amended language, “excluding Indians not taxed,” said nothing of Gypsies and Chinese. Judge Ho’s reliance on Trumbull’s answer to Cowan is wholly misplaced: when Trumbull said “Undoubtedly” he was not expressing his view that the language of the Civil Rights Act should include Gypsies and Chinese. Rather, Trumbull’s aim was to show that if Gypsies and Chinese were included, this was certain proof that everyone born within the geographical limits of the United States were automatically subject to its jurisdiction, but that his intention was to exclude Indians not taxed and foreigners who owed allegiance to other countries.

Trumbull, showing a marked impatience with Senator Cowan, did use language implying that children born in the United States of “Asiatic parents” who were not naturalized citizens, were citizens. But Trumbull says this was already the case under the naturalization laws as they currently existed. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 was the first definition of citizenship after the passage of the 13th Amendment, and there was some question as to whether the amendment provided sufficient authority for declaring the newly freed slaves to be citizens. In any case, the Civil Rights Act’s definition of citizenship did not contain, as did the 14th Amendment, a requirement that those born in the United States must also be “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States, only that they not be subject to a foreign power. It is somewhat anomalous, therefore to use evidence from the debate over the Civil Rights Act as if it contained the same language as the Citizenship Clause of the 14th Amendment.

In the debate over the Citizenship Clause, no one accepted Senator Conness’ argument about Chinese citizenship; it is not even certain that Conness himself did since he made an elaborate case that the Chinese did not owe allegiance to the United States. Further, my opponents have not sufficiently demonstrated from the debates that Gypsies and Chinese were in fact included in the Citizenship Clause of section one.

ENDNOTES

[1] Congressional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., 2768-2769 (May 23, 1866) (Sen. Wade).

[2] Ibid., 2890 (May 30, 1866) (Sen. Howard).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Congressional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., 1291 (Mar. 9, 1866) (Rep. Bingham).

[6] Congressional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2893 (May 30, 1866) (May 30, 1866). One particularly confused law professor, claiming to have discovered the framers’ intent regarding the Citizenship Clause, proclaims indignantly that “[i]f this quote were taken seriously [viz., “not owing allegiance to anybody else”] then dual citizenship would be prohibited.” Since the professor knows in advance that dual citizenship will be essential to the post-nation-state world, Trumbull’s remark cannot be taken seriously. Surely, the professor who believes that it is beyond dispute that the English common law was adopted by the 14th Amendment, must know that the common law prohibited dual citizenship. As evidence of the absurdity of Trumbull’s remark that allegiance has nothing to do with jurisdiction—that jurisdiction means only subject to the laws and courts of the United States—our author cites Chief Justice Fuller’s dissent in Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 720: “[D]ouble allegiance in the sense of double nationality has no place in our law . . .” which fully supports Trumbull. See Gerard N. Magliocca, “Indians and Invaders: The Citizenship Clause and Illegal Aliens,” 10 Journal of Constitutional Law 3 (Mar. 2008), 510 n. 57.

[7] Ibid., 2895 (May 30, 1866) (Sen. Howard).

[8] Robert Tracinski claims that the use of the bracketed “[or]” “is based on a blatant lie,” and falsifies what “the debates in Congress repeatedly affirmed.” The Federalist, July 23, 2018. I am confident that I have “falsified” the allegations of this scribbler and the others who have objected to the now famous bracketed “[or]”. Garrett Epps accuses me of “scholarly malpractice” in using the bracketed “[or]” because it “contradicted the unedited text.” (Garrett Epps, “The Fourteenth Amendment Can’t Be Revoked by Executive Order,” The Atlantic Online, Jul. 19, 2018. I have had occasion to cross swords with Epps before in an online debate about the Citizenship Clause. He accused me of scholarly malpractice because I suggested that Senator Howard had a legitimate claim to be one of the principal authors of the citizenship clause. Epps said the consensus of scholars was that Representative John Bingham was the author of the first section of the 14th Amendment. At the time of the internet debate, I let Epps’ own glaring ignorance pass, saying that it was not necessary to quibble about authorship, because I thought it was important to display some magnanimity to him so as not to embarrass him in front of his progressive-liberal acolytes who might, unlike Epps, be amenable to reasonable argument. What Epps claimed all competent scholars know is simply false. Apparently Epps, the accomplished scholar that he is, was unaware of Bingham’s statement made on March 31, 1871, on the floor of the House: “I had the honor to frame…the first section [of the 14th Amendment] as it now stands, letter for letter and syllable for syllable…save for the introductory clause defining citizens.” The willful misinterpretation of the Citizenship Clause to advance an ideological cause that contradicts the intentions of the framers is the real malpractice—and it is practiced by Epps.

[9] “Defining ‘American’: Birthright Citizenship and the Original Understanding of the 14th Amendment,” 372.

[10] Congressional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., 572 (Feb. 1, 1866) (Sen. Trumbull).

[11] William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1765-69; reprint Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979), I.358.

[12] Los Angeles Times.

[13] Congressional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., 2768-2769 (May 23, 1866) (Sen. Wade).

[14] See Ho, “Defining ‘American’: Birthright Citizenship and the Original Understanding of the 14th Amendment,” 368.

[15] Congressional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2890-91 (May, 30, 1866) (Sen. Cowan).

[16] Ibid., 2891 (May 30, 1866) (Sen. Conness).

[17] Ibid., 498 (January 30, 1866) (Sen. Trumbull).

[18] Ibid.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The 14th Amendment settled the question of birthright citizenship.

The political consequences of cultural freefall.

A reply to the hysterical arguments made by progressive liberals and others who should know better.

The Declaration and the Fourteenth Amendment grasped citizenship through social compact.

It's stronger than you think.