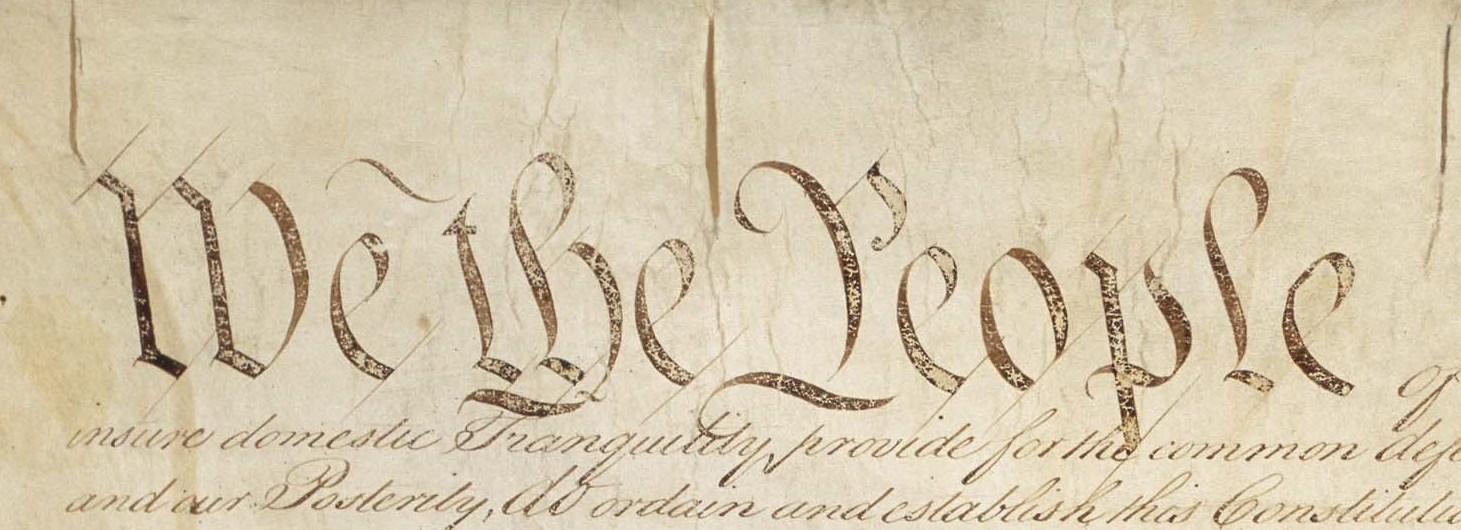

Birthright citizenship should be an uncontroversial right.

It’s the Citizenship, Stupid

The political consequences of cultural freefall.

Why is there a debate about birthright citizenship at all? This is an interesting question in its own right. The widespread assumption is that the answer has more to do with the idea of birthright than the idea of citizenship. It is hard to escape the suspicion that this reactive framing is so knee-jerk because something about the issue of citizenship is so frightening.

And it doesn’t take much to conclude that what’s scary about citizenship is how hollow and irrelevant it has become in American life (as even some vociferous critics of the current administration agree). Though often fearfully unspoken, prevailing attitudes about citizenship as a practice and an obligation remind me of Oscar Wilde’s gibe that the problem with socialism is it takes up too many evenings. The commandments of today’s culture — efficiency, convenience, expression, and entertainment — are totally at odds with the obscure and quotidian labors that the everyday tasks of citizenship entail.

How many Americans want to spend time working with their neighbors — often complete strangers perceived as off-putting weirdos — attending to the petty challenges shared by local communities? How many want to smell the odors of the community center and indulge the tangential monologues of local officials?

Who, to ratchet things up a notch, wants to expend their precious time and life force paying attention to the obscure and quotidian individuals keeping citizenship afloat as something more substantial and dutiful than the perennial panicked plebiscite held on federal election days? Who, to go a notch higher, really wants citizenship to impose anything at all on them? Forget the interminable city council meetings — who wants to submit to a military draft?

Citizenship has lost so much of its genuinely political content — ruling and being ruled in turn — that it has become a moral abstraction. Just as people call each other “sir” in America because nobody is an aristocrat, not because everyone is, “citizen” is now a label predominantly used to confer recognition as a person to whom obligations — in the form of material benefits — are owed.

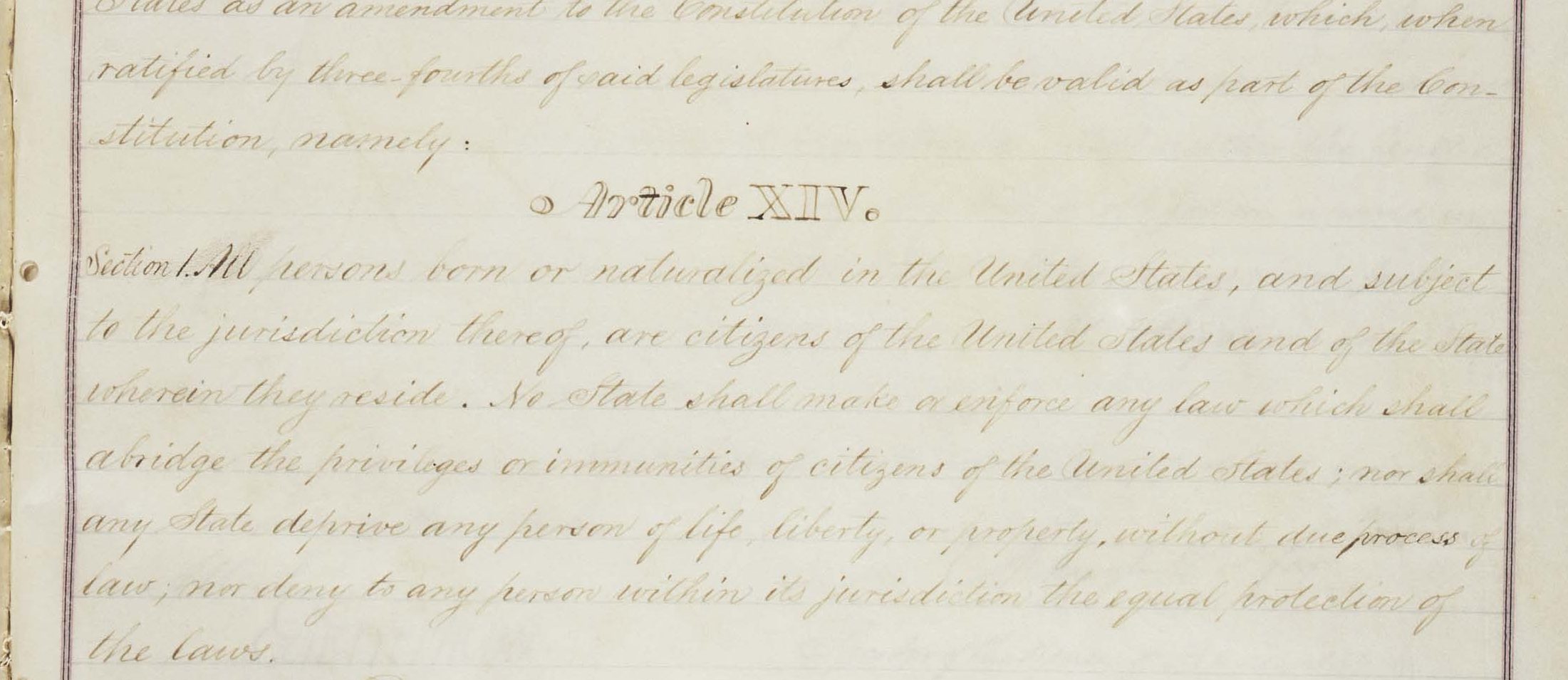

But these material benefits go beyond the social entitlements that, for so many Americans, are the real and final meaning of citizenship. So, when presented with the birthright citizenship debate, scholars such as Andrew Delbanco immediately draw a moral analogy between America’s slaves in the antebellum period and its illegal immigrants today. Citizenship, in their articulation of the prevailing view, is full personhood, officially conferred or recognized. Our human rights to be official persons — life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness safeguarded by the state — are, they hold, our birthright.

Therefore, this line of thinking concludes, US citizenship must be a birthright to those in the United States, because the effective truth of citizenship is that it is personhood. People inside the United States who are not citizens (and enjoy no temporary legal status) are therefore, intolerably, unpersoned.

This logic pushes a powerful, paradoxical moral imperative to not do what so clearly needs to be done — namely, to restore the political content of citizenship as a duty among neighbors to practice ruling and being ruled in turn. By this logic, prioritizing the restoration of citizenship as a practice, and not just a status, unacceptably risks exposing noncitizens to depersonalization. All attention must be focused on ensuring that all people in the US have the personhood which, at bottom, only the conferral of citizenship can truly ensure. American citizenship is not an obligatory practice wherein people exercise their natural rights close to home, but an obligatory conferral of that to which humans anywhere are entitled by their natural rights.

The reality in America is that these two understandings of citizenship have always intermixed — and often reinforced one another. But today they are unnaturally at odds, in large measure because the course of American culture and politics has led so potently away from the habits and mores of citizenship as practice. The tetrad of values that came to rule our social imaginary — entertainment, enlightenment, empowerment, and emancipation — demands of citizenship as practice the same as it does of so much else in everyday life: a maximum of felt payoff from a minimum of input. Citizenship as practice cannot be fully restored, nor can citizenship as status be brought back into its proper relation with practice, until the iron cultural framework of this tetrad is broken.

But the debate over birthright citizenship has revealed two important things about the tetrad. First, the authority of the tetrad has begun to weaken so quickly in recent years that interest in citizenship as status-plus has begun to increase sharply. An awareness is setting in that a regime of citizenship as status cannot prevent American democracy from devolving into a periodic rubber stamp for the fiat of a permanent managerial elite.

Second, the arrival of a full-on debate about birthright citizenship has shown that the context of the debate is in some ways even more important than the content — because the context is not up for debate. It is clear, it is settled, and it has already shaped us in ways that exert an irrepressible influence on what is to come.

Americans are well aware that, so far, the disruptions and transformations caused by the dawning triumph of digital technology over our psychological and social environment have done more to hurt than help both America’s meritocratic elite and its struggling citizenry. Our elite conditioned our citizenry to expect that, because we created digital tech, it would perfect the moral universe of citizenship-as-status. In fact, nearly the opposite happened. Polling shows the center of gravity in American politics now belongs to an “exhausted” middle. Recent history reveals the bipartisan elite, in both the Bush and Obama administrations, completely failed to maintain the dominance of American interests and the prestige of American values during the opening stages of the digital transition.

Most people today are not just exhausted by everyday life or politics in a general sense, but by the pillars of the contemporary cultural triad themselves. The entertainment promised by ads and fantasies is no longer enchanting. The enlightenment promised by news is experienced now as a scam. The empowerment hawked by gurus and activists is leading to deep disillusionment. Instead of emancipation, many simply feel freefall.

This is the context that has made the unthinkable — a debate about birthright citizenship — possible. And because it was until recently so unthinkable, fear is spreading, however unspoken, that (a) more unthinkable things are about to happen; (b) we won’t see them coming until it’s too late; and (c) we won’t even have time to properly equip ourselves for life in the Unthinkable Age that is just around the bend.

These concerns are justified. But in an America where citizenship ceases to signify a shared practice of mutual governance, these concerns are useless.

Photo Credit: Sen. Claire McCaskill

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The 14th Amendment settled the question of birthright citizenship.

A reply to the hysterical arguments made by progressive liberals and others who should know better.

The Declaration and the Fourteenth Amendment grasped citizenship through social compact.

A reply to Professor John Yoo's and Judge James Ho's case for the original understanding of the 14th Amendment.

It's stronger than you think.