The 14th Amendment settled the question of birthright citizenship.

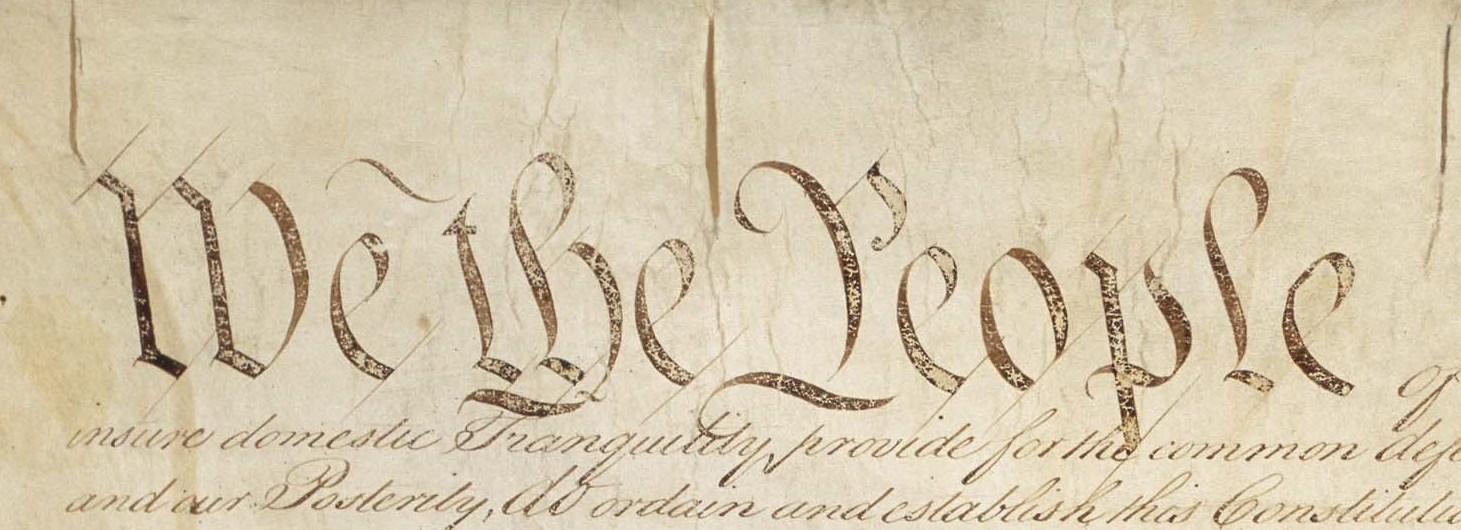

The 14th Amendment’s Promise

Birthright citizenship should be an uncontroversial right.

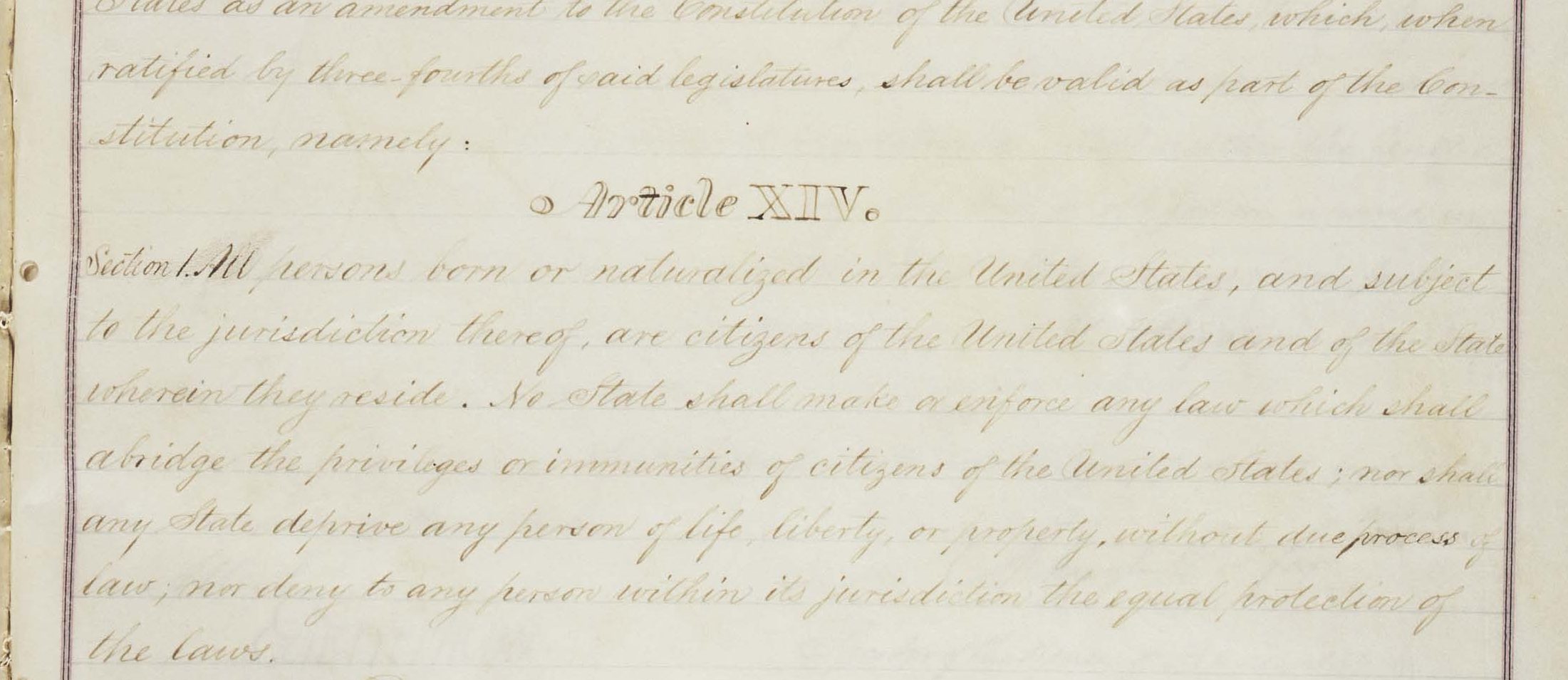

For much of its history, the 14th Amendment’s promise that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and the states wherein they reside” has been uncontroversial. Few questioned that the words meant what they state in plain English or imagined that phrases within the amendment should be parsed to exclude children born to immigrants. Those who opposed birthright citizenship were outside the mainstream of Constitutional scholarship and found few allies in policy circles. But with hostility to immigration, legal as well as illegal, becoming more prevalent in the Age of Trump, it should be no surprise that efforts to reinterpret the 14th Amendment are gaining momentum.

I have argued elsewhere at length why the reinterpretation of the 14th Amendment to exclude from birthright citizenship children born to illegal immigrants is ahistorical and inconsistent with Supreme Court rulings, but there is a more fundamental issue at stake. This is no mere academic argument or high-brow debate about the social compact and the consent of the governed, as Michael Anton and others claim. The aim is to strip millions of people who were born here of their right to U.S. citizenship. The effort is part of an orchestrated campaign to redefine what it means to be an American and who should be entitled to protection of our laws and Constitution.

Despite the recent increase in the number of families entering the country illegally (some of whom are seeking asylum), the overall problem of illegal immigration has diminished over the last decade, not increased. Currently, some 11 million illegal immigrants live in the United States. That number has remained relatively constant in recent years, falling from its peak of more than 12 million in 2007. Two thirds of illegal immigrant adults have lived here for more than a decade; only 14 percent have lived here less than 5 years. Illegal border crossings are now at their lowest point in nearly 50 years, thanks in large part to more effective border control.

Most of those who come here illegally do so because there are no viable avenues under current immigration law for them to come legally to fill jobs in certain industries that Americans shun. These undocumented immigrants work (comprising 5 percent of the civilian workforce), pay taxes, set down roots, and have families in communities across the nation. Nearly 5 million American-born children under age 18 live in households with at least one parent who is illegally present, though the number of babies born to illegal immigrants has declined since its peak in 2006.

These children will grow up here, speak English as their preferred language, attend American schools and colleges, join the U.S. military, enter the workforce, and contribute to their fellow Americans through their taxes and participation in the economic and the civic life of the nation. They are no less American in any meaningful way than those whose parents were born here, nor has the law treated them as anything but citizens throughout their lives. Yet, opponents of birthright citizenship would cast these millions into a state of legal limbo, subjecting them to the possibility of deportation to countries most of them have never set foot in and whose language they may not even know.

It would be bad enough if the anti-birthright citizenship forces were arguing that we must rethink U.S. citizenship in light of current circumstances and amend the Constitution prospectively to change a practice, in place since the Founding, that has granted citizenship to all persons (with the exception of diplomats’ children and, for a time, Indians and slaves) who are born on U.S. soil. Now some in this movement argue that the president acting on his own has the power to declare that the children of illegal immigrants are not citizens. So much for the importance of “consent” on which these opponents rest their intellectual case against birthright citizenship. Why bother with a debate in Congress, where Americans’ elected officials would be forced to grapple with the gravity of what is proposed, when Donald Trump can revoke citizenship for millions of “undesirables” with the stroke of a pen?

The history of this country has largely been one of expanding the definition of who is entitled to full participation as citizens. Efforts to restrict citizenship—from the Dred Scott decision to the Asian exclusion laws—have eventually been rebuffed as we came to see them as inconsistent with our national character and aspirations. I have little doubt that the attacks on birthright citizenship will meet the same fate.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The political consequences of cultural freefall.

A reply to the hysterical arguments made by progressive liberals and others who should know better.

The Declaration and the Fourteenth Amendment grasped citizenship through social compact.

A reply to Professor John Yoo's and Judge James Ho's case for the original understanding of the 14th Amendment.

It's stronger than you think.