Birthright citizenship should be an uncontroversial right.

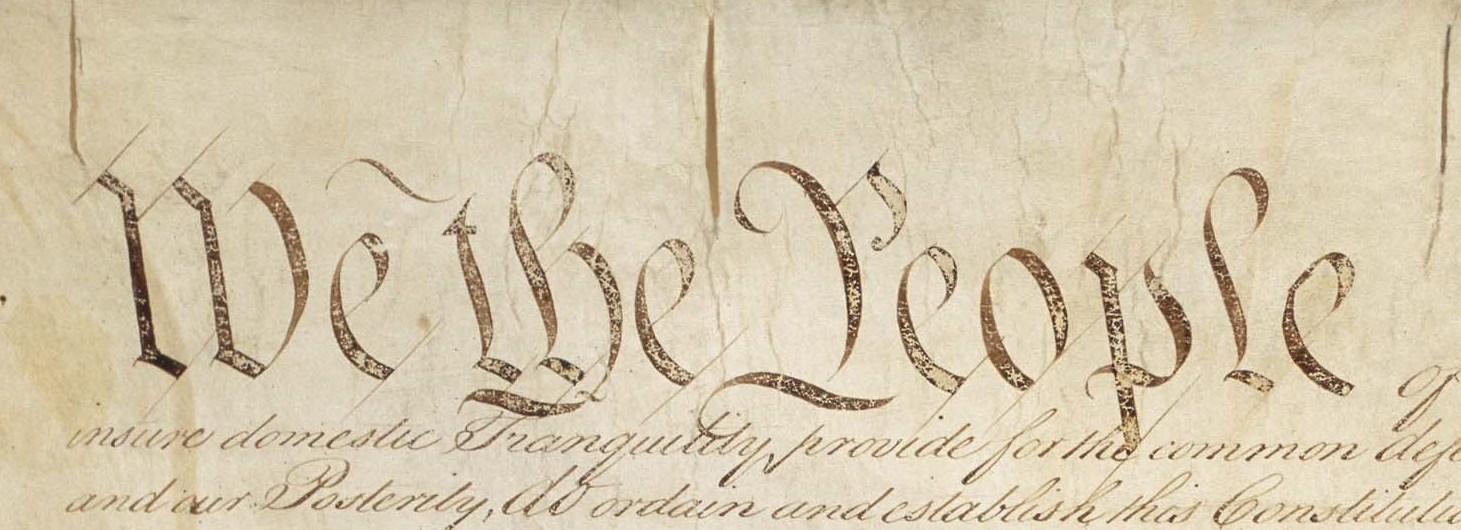

Settled Law: Birthright Citizenship and the 14th Amendment

The 14th Amendment settled the question of birthright citizenship.

President Donald Trump’s call to end birthright citizenship has sparked a national debate. Within the Republican party, leading voices differ on the legitimacy of citizenship as a birthright. While some embrace the traditional view that the Constitution bestows citizenship on any citizen born on U.S. territory, others agree with Trump that the Constitution permits Congress to decide on citizenship for those not born to U.S. citizens. Alternatively, some acknowledge birthright citizenship, but seek a constitutional amendment to abolish it.

Recently, the White House established a Citizenship and Immigration Services task force to denaturalize American citizens who gained citizenship through improper or questionable means. In addition, Trump administration members have vocally called for a stop to birthright citizenship entirely. As former national security official Michael Anton wrote in a recent op-ed, “the notion that simply being born within the geographical limits of the United States automatically confers U.S. citizenship is an absurdity–historically, constitutionally, philosophically, and practically.”

Conservatives should reject Trump’s nativist siren song and reaffirm the law and policy of one of the Republican Party’s greatest achievements: The 14th Amendment. According to the best reading of its text, structure, and history, anyone born on American territory, no matter their national origin, ethnicity or station in life, is an American citizen.

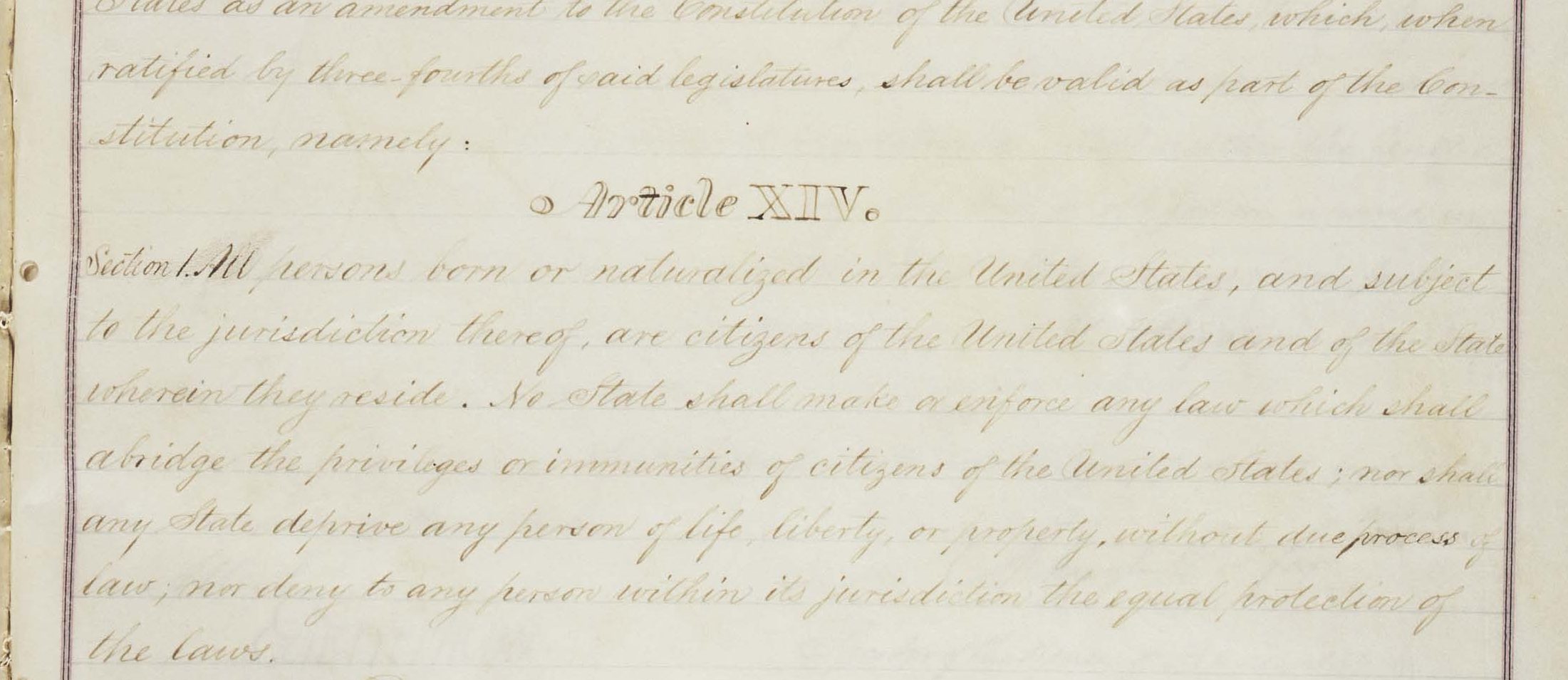

While the original Constitution required citizenship for federal office, it never defined it. The 14th Amendment, however, provides that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” Congress did not draft this language to alter the concept of citizenship, but to affirm American practice dating from the origins of our Republic. With the exception of a few years before the Civil War, the United States followed the British rule of jus solis (citizenship defined by birthplace), rather than the rule of jus sanguinis (citizenship defined by that of parents) that prevails in much of Europe.

As the 18th century English jurist William Blackstone explained: “the children of aliens, born here in England, are generally speaking, natural-born subjects, and entitled to all the privileges of such.”

After the Civil War, congressional Republicans drafted the 14th Amendment to correct one of slavery’s grave distortions of our law. In Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857), Chief Justice Roger Taney found that slaves, even though born in the United States, could never become citizens. The 14th Amendment directly overruled Dred Scott by declaring that all born in the U.S., irrespective of race, were citizens. It also removed from the majoritarian political process the ability to abridge the citizenship of children born to members of disfavored ethnic, religious, or political minorities.

The only way to avoid this straightforward understanding is to misread the 14th Amendment’s text, “subject to the jurisdiction thereof,” as an exception that swallows the jus solis rule. Some originalist scholars, such as John Eastman and Edward Erler, argue that this language must refer to aliens, who owe allegiance to another nation and not the U.S.

I believe that view is mistaken. The 14th Amendment’s reference to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof” refers to children who are born in U.S. territory and are subject to American law at birth. Almost everyone present in the United States, even aliens, come within the jurisdiction of the United States. If the rule were otherwise, aliens present on our territory could violate the law with impunity.

Critics, however, argue that “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” must refer to those who bear allegiance to the United States, i.e., those whose parents are already citizens. Otherwise, the argument, goes, the jurisdiction language is redundant with being born on U.S. territory. But at the time of the Framing of the Constitution and of the Amendment, there were discrete categories of persons who could be on U.S. territory but no subject to our laws, such as diplomats and enemy soldiers occupying U.S. territory during war. International law grants both diplomats and enemy soldiers protected status, when present on the soil of another state, from the application of that state’s laws.

At the time of the 14th Amendment’s ratification, one other group was not subject to U.S. jurisdiction. American Indians residing on tribal lands were not subject to U.S. law because the tribes exercised considerable self-governance. In the late 19th Century, the federal government began to regulate Indian life, substantially diminishing tribal sovereignty, and in 1924 extended birthright citizenship to them.

The 14th Amendment’s drafting history supports this reading. The Civil Rights Act of 1866, which inspired the Amendment, extended birthright citizenship to those born in the U.S. except those “subject to any foreign power” and “Indians not taxed.” If the 14th Amendment’s drafters had wanted “jurisdiction” to exclude children of aliens, they easily could have required citizenship only for those with no “allegiance to a foreign power.”

Significantly, congressional critics of the Amendment recognized the broad sweep of the birthright citizenship language. Senator Edgar Cowan of Pennsylvania, a leading opponent, asked: “is the child of the Chinese immigrant in California a citizen? Is the child born of a Gypsy born in Pennsylvania a citizen?” Senator John Conness of California responded yes, and later lost his seat due to anti-Chinese sentiment in his state. The original public meaning of the 14th Amendment—which conservatives properly believe to be the lodestar of constitutional interpretation—affirms birthright citizenship.

The traditional American position, finally, works no great legal revolution. The Supreme Court has consistently read the 14th Amendment to grant birthright citizenship. United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898) upheld the American citizenship of a child born in San Francisco to Chinese parents, who themselves could never naturalize under the Chinese Exclusion Acts. The Court held that “the Fourteenth Amendment affirms the ancient and fundamental rule of citizenship by birth within the territory, in the allegiance and protection of the country, including all children here born of resident aliens.” It also explicitly rejected the argument that aliens, because they owed allegiance to a foreign nation, were not within “the jurisdiction” of the United States.

Critics of birthright citizenship respond that Ark did not involve illegal aliens and therefore doesn’t apply to children of undocumented migrants. (While Ark’s parents could not become citizens, they could reside here legally.) But in 1898, federal law did not define legal or illegal aliens, and so the Court’s opinion could not turn on the legal status of Ark’s parents.

In Plyler v. Doe (1982), moreover, the Supreme Court held 5-4 that the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause required Texas to provide public schooling to children of illegal aliens. All nine Justices agreed that “no plausible distinction with respect to the 14th Amendment ‘jurisdiction’ can be drawn between resident aliens whose entry into the United States was lawful and resident aliens whose entry was unlawful.”

Proponents of “allegiance” citizenship also do not appreciate the consequences of opening this Pandora’s box. Among other things, their standard could spell trouble for millions of dual citizens, who certainly owe allegiance to more than one country. This is not entirely speculation; during World Wars I and II, public sentiment ran strongly against German-Americans or Japanese-Americans.

More generally, the whole notion of national loyalty is open-ended, requires person-specific determinations and would put the government in the business of reviewing the ancestry of its citizens. Washington, D.C. and the states would have to pour even more resources into an already dysfunctional bureaucracy that cannot even control the borders. Reading allegiance into the 14th Amendment would largely defeat the intent of its drafters, who wanted to prevent politicians from denying citizenship to those they considered insufficiently American.

The 14th Amendment settled the question of birthright citizenship. Conservatives should not be the ones seeking a new law or even a constitutional amendment to reverse centuries of American tradition.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The political consequences of cultural freefall.

A reply to the hysterical arguments made by progressive liberals and others who should know better.

The Declaration and the Fourteenth Amendment grasped citizenship through social compact.

A reply to Professor John Yoo's and Judge James Ho's case for the original understanding of the 14th Amendment.

It's stronger than you think.