In our end is our beginning.

Promoting Ourselves to Death

America’s aesthetic movements must resist commodification.

When I was in the 7th grade, my small-town American public school district mandated that students take a “Careers” elective. In class, we learned how to mine our recent childhood for marketable experiences and artfully apply them to the document that would henceforth determine our status (i.e. fate) in life: the résumé.

At the tender age of 12, we used a thesaurus to replace synonyms for synonyms, to better conform to the corporatespeak favored by the employers and admissions officers who would soon enough determine our status-fates. Can’t a gardening class make me an expert in synergistic biodiversity? Doesn’t acting in the school play constitute “community service”? Why not?

In the early part of the digital age the résumé—newly permanent, accessible, and social-media ready—took on added weight. We downloaded the right templates. We kept databases of the appropriate verbiage. We learned to match the way we presented ourselves online to the flowery language of college brochures fervently and indiscriminately distributed by our school guidance counselor.

In one way or another, then, we were indoctrinated in the art of self-promotion—not the collection of qualifications in an objective, matter-of-fact kind of way, but the arbitrary fusion of our subjective identity with algorithmically desirable qualities and credentials. No good deed went unpublished.

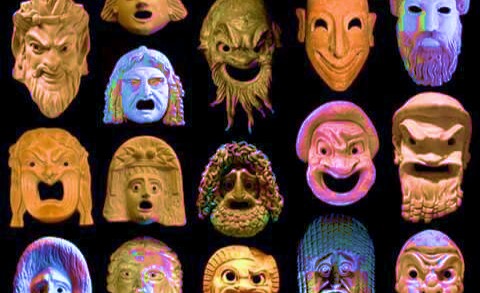

We know, because Curtis Yarvin (formerly Mencius Moldbug) tells us in “The Deep State Versus The Deep Right,” that regimes are implicitly aesthetic experiences. By extension, revolutions are at their core aesthetic breaks from a dominant narrative. If we are to self-examine in light of his proposition, we might get at the nature of the American regime by asking: what is the aesthetic experience of that regime?

Within the general aesthetic experience of America there are multiplying subcategories: city planning, architectural design, education, fashion, and food, just for starters. But these visible manifestations are united by an aesthetic principle, a deeper force from which they spring. This principle is “how we perceive,” as Micah Meadowcroft and Joseph Keegin point out in their response to Yarvin, which “determines in large part what we perceive.”

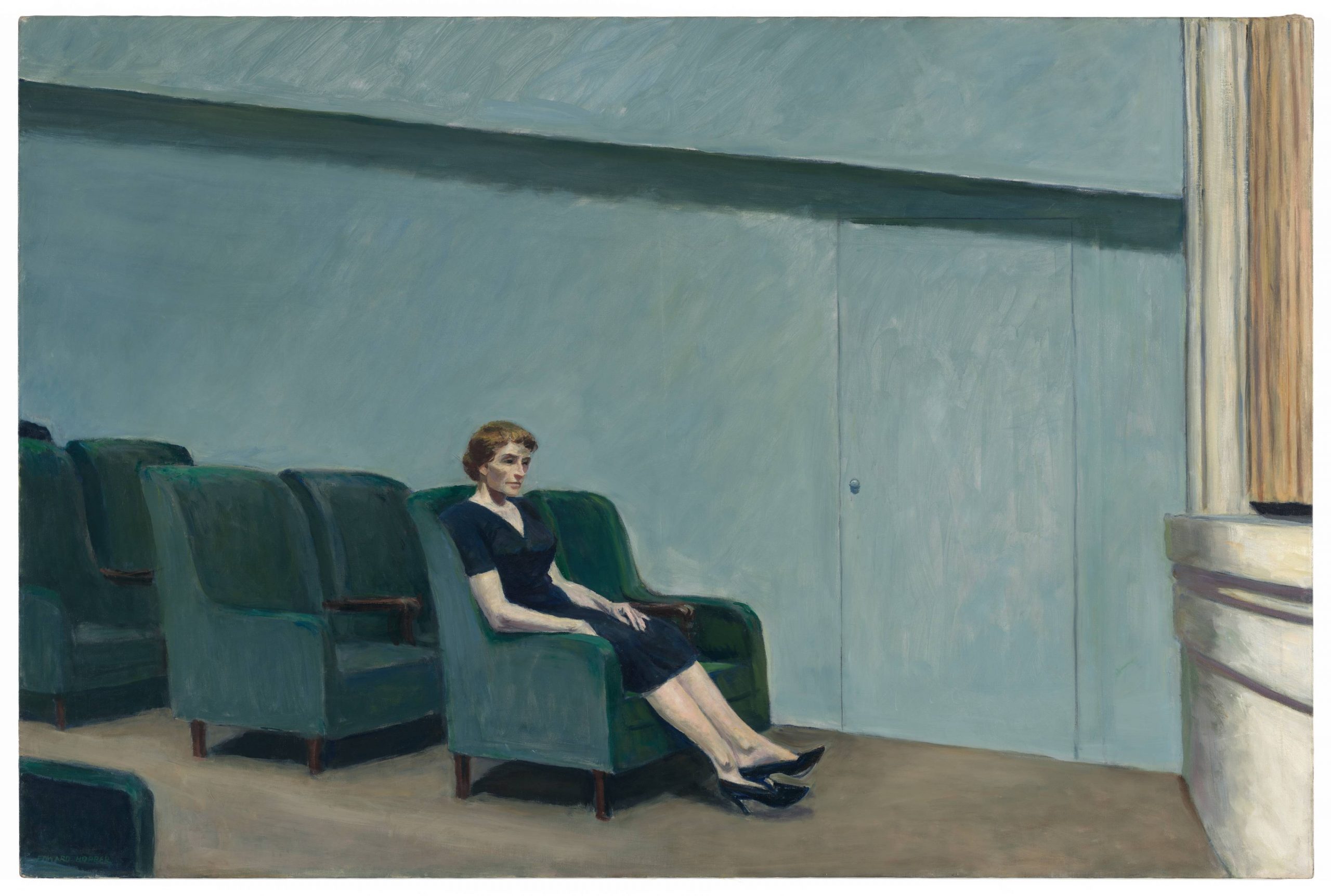

In America, unmoored liberalism (social and economic) frees us from all convention. It leaves us with no past and no future, no beginnings or ends. The present-day American is, by and large rootless historically, geographically, spiritually. Broad deracination primes the individual for isolation, relational anxiety, and, ultimately, desperate conformity. As a result, all is dissolved into the same manic desire for recognition, manifested perfectly in the fetishism of the résumé.

As a matter of course, then, Americans become totally driven by the act of achieving for the sake of being seen. We perceive in terms of how we might be seen. For similar reasons many of us still cling amorously to the television. TV gives us our gods. Online, the diminishing returns of worshiping these gods are self-evident. The celebrity becomes the influencer becomes the micro-influencer becomes the flavor of the minute—all yearning to be celebrated, yes, but most primally of all, to simply be seen. In fact, our the social and spiritual vacuum of our rootlessness is our way of seeing, whether we know it or not. The American aesthetic principle is to efficiently manage our own rootlessness and its psychological externalities. We shop. We self-medicate. We eat. We post.

It’s Time to Play…Categories!

This manner of perception leads different categories of Americans to play different yet complementary parts in the production of the political aesthetic. As “class” can be a quite messy classification, each groups’ actual roles in this process are probably more appropriate categorizations anyway. There are basically three, plus one: legacy elite, strivers, untouchables, and true elite.

The legacy elite are those who own the means of ideological production: the CEOs of America, Inc. This includes our media, academia, tastemakers, string-pullers, foundation-starters, and the like. They are neither artists nor experts, really. (Truly excellent artists and intellectuals belong in their own category, true elite, but more on that momentarily.)

The legacy elite are the relatively private, monied powerful who choose which artists and experts come to light, become verified on social media, reach the platforms, make a living. They are the aesthetic standard-setters.

One status rung down are the strivers. These are the talented Mr. Ripleys of the world: journalists, yuppies and wannabe yuppies, empty vessels, seduced by the prospect of elitism and mystified by the promises of meritocracy. Maybe I’m a striver; I was certainly bred that way.

Strivers’ defining features include slavish devotion to the ephemeral ideological whims of those of their superiors, intense competition with one another for recognition and validation from higher-ups (utter alienation as a group), and the use of highly feminized social enforcement to justify their position in the hierarchy. They dream other people’s dreams, the right dreams. They do it well, and they expect to be well compensated, financially, culturally, and cosmetically.

Strivers keep a meticulous résumé. Strivers cry when celebrities die. Strivers are satisfied by pressing play and playing along. The semblance of status and the myth of upward mobility have long insulated them from thinking too deeply about the cracks in the yellow brick road.

Strivers manage the entrenched system by force, and enforcement occurs through feminine and feminizing relational aggression. If preservation of his participation in a white collar, salaried, university-emblazoned bumper-sticker social stratum is the striver’s carrot, Tiger King is his stick. The working class, in the current political portrait of America, becomes the terror of dreams and the butt of jokes: a brutal example of what happens when you fail to buy in on an ideological level to the narrative of striving generally, as well as to the political narrative du juor.

Striver-enforcers use the dehumanizing practice of cancellation to scrub rougher, traditionally working-class sentiments, expressed by whomever, out of existence. Because their identity is based on consensus, dissent is a threat to their very core. Those who express this lack of awareness in one way or another are untouchables. Thus, cigarette-puffing working class people are functionally defined as counterexamples, negative reinforcement for the regime’s dominant narrative.

This slander plays out, like much aesthetic experience today, televisually. The villains in Taylor Swift’s “You Need to Calm Down” music video are, by appearance, straight out of a Dorothy Allison novel. But there’s nothing complicated (read: humanizing) about them on TV. Working-class dissent is implicitly coded as lack of self-awareness, integrity, dignity, etc. The attacks, often racial and classist in nature, make authentic working-class solidarity and, by extension, political action, a near impossibility.

Talent is the self-evident defining feature of our final category. True elites are the artistic and intellectual talent of the times; they have the aesthetic awareness, but rarely the power. Driven to the fringe, they find themselves aligned with untouchables more often than not. Being motivated by something other than social acceptance in this world makes you more prone to cancellation.

Glitches in the Matrix

In order to better understand the versatility of the regime, consider recent revolutionary political moments in terms of competing aesthetics. These were moments that felt like a break in the matrix, moments when those unforeseen, gaping plot holes irreversibly disfigured the lifescript we’d always followed as a matter of course. Yarvin suggests that regimes become vulnerable when their institutional mendacity is exposed. In the following examples, exposure came to light through rhetorical and aesthetic competition.

Occupy Wall Street was the first in my memory. Overeducated, underemployed young people, who had thus far followed the institutionally sanctioned path to success, discovered soon after the 2008 financial crisis that their prospects ran dry. For all of that movement’s lack of focus and anarchic subversions, the kernel of truth that broke through the public conscience was in its notorious slogan: “We are the 99%.”

Many weren’t. Many were a portion of the maybe 30% that eventually found bullshit jobs in the “information economy.” Strivers then and strivers now, except now they might have health insurance. But because occupy activists, unlike the actual working class, had been trained up in verbal acuity, they stated the case effectively.

Despite themselves, it was eminently true that this generation had been strung along and ultimately left behind by the broken mechanism of a burnt-out dream. The “99%” painted a picture of solidarity that stood in stark contrast to the every-man-for-himself financial environment of the times. The aesthetic of community out-competed that of competition, if but for a moment.

The 2016 election was another glitch, and in many ways an outgrowth of similar resentments: the ruthless careerism of the Clinton regime met an unrefined H.R. nightmare in Trump, and lost. Charisma usurped credentialism. Trump voters, which included veterans failed by the promises of honor in military service and many more workers and washed out strivers failed by the promises of media darling Obama, found themselves voting with their gut, belly laughing as Trump’s casual dismissal of the elite’s dream paradigm scandalized the tastemakers of America, Inc.

For a moment, embodied reality seemed to reassert itself against its state-sanctioned, bloodless representations; Trump’s guileless, chaotic energy simply felt more politically authentic. His offensiveness better matched the frustration of many Americans’ interior lives. Normie Left and Right still fail to realize that the Trump moment, however ironically, presented an aesthetic continuation of Occupy. These were moments borne of the same revolutionary resentment toward the oppressively isolating banality of American neoliberal, neoconservative ideals.

But the elite and the entrenched, however hapless, have the tendency to double down and eventually capitalize on the crises that initially shake them. Legacy elite know that the spiritual emptiness and status-obsessed eagerness of this class makes them malleable.

After Occupy, Goldman Sachs bought a float in the NYC Pride Parade. The corporation and its peers fully incorporated the tenets of multiculturalism into their hiring practices, and began mandating “[Insert Aggrieved Victim Category] in Business” seminars for their employees. Many of the so-called radicals that inserted themselves along the vanguard of wealth parity politics now implicitly accept this brand of woke capitalism as recompense.

Once strivers have taken up a new flag, woe be to whoever does not immediately and unthinkingly submit. Thus the heart of the radical Left ceased beating. No one understands the power of false consciousness in competition like the Cathedral.

The spiritual breakthrough of Trump’s election was briskly extinguished, too, as the institutions his election threatened (media, academia, “the Deep State”) dug their heels in harder than ever before, launching a series of personal cancellation campaigns, Russiagate, impeachment, and on and on.

Certain strivers (grifters) fashioned themselves as Trumpists in opposition to the opposition, all the while dispensing entirely with the intellectual foundation of the revolution. Many of the dissidents who led and inspired the Trump campaign, some of the most intellectually serious people I know, have closed the door on their MAGA hats gathering dust in the closet. No one understands the power of demoralization in competition like the legacy elite that needs its spell unbroken.

The Territory Ahead

The artist-hero of Yarvin’s proposition must gird his loins against the form of commodification to which Occupy succumbed, and if possible, aesthetically undermine the tendency toward commodification itself such that followers don’t find themselves willing to sell him up the river. Yet somehow still, he and his followers must disabuse themselves totally of the desire to be accepted. As Yarvin puts it, “while the great will never lack followers, counting followers never brought greatness to anyone.”

True elites already understand the aesthetic principle of American life: its hollowness, its ugliness, its lies. Failure to see that is never the actual hindrance to their aesthetic dominance, because that failure would render them members of a lesser category. Any new elite will only make an effective aesthetic break with our soulless and phony regime if each artist and intellectual understands their true enemy to be the psychology of the striver.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Does Curtis Yarvin understand Aesthetics?

Now more than ever, there is no way to solve the problem of men.

A city of heaven returns to our barren earth.

New artifacts overthrow old impostures.