A proper national politics naturally protects both our shared prerogatives and our individual rights.

Pull the Plug on Fun Time

Our federal and academic bureaucracies have had it too good for too long.

Christopher DeMuth’s “Trumpism, Nationalism, and Conservatism” is a significant essay outlining how American conservatism should responsibly incorporate the nationalist framework that has risen with Donald Trump’s politics and administration. DeMuth observes that “when President Trump has finished his work, the conservative movement and Republican Party will not be the same. The result will not be a mid-point between Trump and John Kasich. Rather it will be a fresh formulation of what it means to be conservative or libertarian in the modern age.”

Importantly, the prior order of American conservatism—the one that Trump entombed—was heavily informed by libertarian theory and, in this, it failed to understand the political realm. Instead, the old conservative mode of discourse chose a kind of political quietism that robustly defended markets and growth as the real spirit, or even the purpose, of public life. No political leader exemplified this better than Mitt Romney, whose failed 2012 presidential campaign featured rote rhetoric about entrepreneurial capitalism, job creators, the failure of the Obama economy, and Romney’s prescriptions for economic vitality. Romney kept his words and his thoughts far from the crucial public concerns of his own electorate. Not so, Donald J. Trump. Though his rhetoric triggers a rash of other problems, it betokens a host of opportunities as well.

The Fanaticism of the Center

DeMuth captures our politics quite accurately with the typologies of “Somewheres” and “Anywheres” he borrows from British political thinker David Goodhart. The Anywheres are the relatively small class of elite individuals in corporate, finance, media, and academic pursuits, for whom borders are quaint if not irrelevant to their pursuit of the good life. We might describe this cohort as those who see themselves in the oxymoronic appellation “citizens of the world.” They fail to acknowledge their cultural debts and seem incapable of expressing gratitude for what they have been given by their country and its traditions.

I wonder, though, if this class is better understood as an attitude or an aspiration that its members live—an identity, not a lifestyle. Outside of the corporate finance guys, is there really a significant class of media, academic, and corporate professionals who are constantly on the move, this year in Washington, next year in London, and then back to Zurich? Maybe, but my sense is that the transnational progressivism captured by the term “Anywheres” is a territory of the imagination—a state of ahistorical mind that wishes to displace the temporal depth of tradition, nature, and constraint that national political borders concretely express. This is the mindset that affects elites in Brussels, London, and Washington D.C.

We also have the “Somewheres,” or the men and women who are from a particular place and work and live in that place. It’s home, and why would you ever leave it? Thus, we understand their frustration and their willingness to speak in an aggressive political fashion the last few years against the loss they sense the Anywheres are imposing with their dreams on the reality of the Somewheres’ homes.

Strengthening DeMuth’s analysis is Pierre Manent’s notion of the immoderate middle—the fanaticism of the center—in political establishments of western democracies. Manent notes that politics in virtually every modern western democracy was guided by the notion of two distinct but legitimate modes of politics: The Left and its social class and the Right and its national people. Both the Left and the Right, however, moved away from their constituencies in the post-Cold War period, choosing instead abstractions or aspirations like globalization, the autonomous individual, liberal democracy promotion, and humanitarian progress.

In late twentieth century America, we witnessed the convergence of leaders of both parties on immigration, trade, many social issues, and foreign policy. These issues were considered settled. With the fracturing of that settlement emerges a new version of authorized politics, i.e., the establishment center, and a new version of unauthorized politics, i.e., populist conservatives. Thus, we have a “resistance” politics now defining the Democratic Party.

Might we also see the “Corbynization” of that party—defined by British journalist Kyle Orton as the toleration of anti-Semitism, a welcoming posture to avowed national enemies, support for domestic policies with no prospect of being funded or of being workable (i.e., the Green New Deal), and radical enthusiasms driving the party?

Declarative Government versus Representative Government

The resistance Democrats will likely give in to the reality that half of the country isn’t illegitimate or even deplorable. What would significantly aid this maturation process is the dethronement of what DeMuth calls “declarative government”, or rule by bureaucracies and Supreme Court opinions on contested social issues. Declarative government produces an incredibly contentious national political life. The key point DeMuth makes is that declarative government, unlike representative government, not only fails to take in the full range of interests that will be affected by an order—regulation, opinion, or informal guidance letter—but it is government heavily shaped by the Anywheres. The hope for the Somewheres is representative government or government that secures consent through debate and compromise of interests—and will thus represent the Somewheres exactly where they are.

DeMuth recommends the revival of Congress as the first plank in his conservative nationalism plan. How one does this is a question many are asking. There seem few good answers. I’m not generally persuaded by DeMuth’s proposals here, but they are worth discussion. My position is much gloomier than DeMuth’s, congressional government returns when its members understand that interest, honor, and shame compel a disciplined and powerful course of action. When that moment happens, then DeMuth’s counsels become more operational.

DeMuth also counsels that the other two federal branches and the two political parties could boost the spirit of representative government. The Supreme Court could induce Congress to resume its constitutional lawmaking powers by limiting the Court’s own Chevron deference doctrine. The effectual truth of the Chevron doctrine is that it permits Congress to send legislation with delegated grants of power to executive agencies intending the real law-making to be done by the agency’s experts, not the actual lawmaking body of government.

But I think a more likely development is the curtailment of the so-called Auer deference, whereby agencies are permitted to interpret ambiguities in their own rules, allowing them generally to profit at the appropriate political time from their own strategic ambiguity. Kisor v. Wilkie, recently argued before the Court, featured exactly this argument by counsel for a Vietnam veteran who was denied full benefits for his PTSD diagnosis by Veterans Affairs because of how that Department interpreted its own regulatory term “relevant.” As counsel for the veteran noted, “relevant” can mean exactly what the VA wants it to mean, thus its use in the regulation.

Could the Court incentivize Congress to be more active in law-making if in a post-deference world agency hands would be more subservient to Congress? If so, such change would happen only at the margins of congressional power. Absent a republican ethos re-informing the Congress, if the Court retrenches the deference doctrines the congressional-agency nexus will only re-emerge again over time as Congress finds new ways to delegate its power to agencies—and the federal courts, with their own limitations, slowly acquiesce to the inevitable.

Could the president aid Congress’s revival? DeMuth describes a scenario of a president exercising power jointly with the Congress to give him stronger national appeal. That transactional relationship would be secured by a nationalist Republican president who recognizes that his own executive bureaucracy is his biggest enemy. He gains leverage over it by working with Congress to craft a popular agenda that must be faithfully implemented by the bureaucracy. Congress recognizes and welcomes the agenda because the president pre-commits to following certain norms that respect it as an institution. As DeMuth notes, such a course would require a statesmanlike president willing to stick to such an agenda in the smooth and the rough of political weather.

Yet the political imaginations of many members of Congress are limited, to put it politely. A better course for Congressional recovery of power will only emerge from a palpable sense of shame on the part of its members toward their own institutional impotence, and the knowledge that Congress’s approval rankings hover somewhere between the Kardashians and cancer. Enough of its members must realize that they are an embarrassment for Congress to achieve the beginning of wisdom.

Finally, political parties must grow in strength: “Party reform would aim to establish a hierarchical, willful Congress through the medium of hierarchical, willful parties,” as DeMuth puts it. That seems a tall order, but DeMuth’s emphasis on the need for strong parties is the right note. The key would be campaign finance reform that unwinds McCain-Feingold, generally letting the parties rake money in, coordinate with member campaigns, and get loyal members re-elected. Parties have been displaced in many respects by entities like so-called 527s that spring up with each finance reform package. If parties are to have power and discipline over their members, control over money is key.

Education and American Purpose

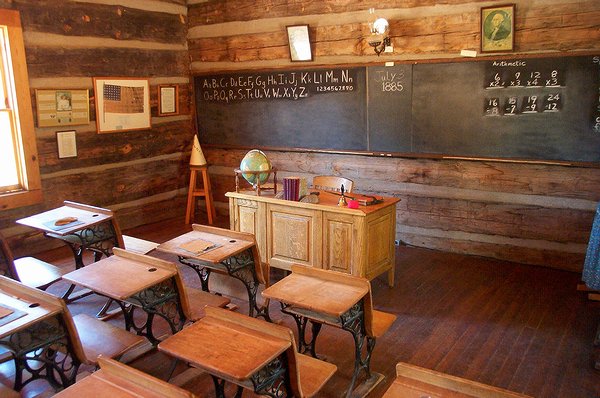

DeMuth next argues that a conservative nationalism will make American identity and purpose a central part of its platform. Education, he says, must be ordered to equal opportunity and income mobility. This can be accomplished by making K-12 education more competitive and locally controlled by means of federal incentives for charter schools, vouchers, and vocational options in high school. Second, higher education must be forced to firmly commit itself to the First Amendment, namely on speech—and I would add religious liberty—or else lose the federal financial aid and research dollars coveted (and needed) by the modern university.

This is a strong set of proposals, and under current political conditions they are much better than the current course. Still, my instinct here is to remove the federal government as much as possible from education at all levels. That may be what DeMuth is ultimately aiming at, but I can foresee a future course of federal intertwinement in charter schools and vouchers that will make us wish we had never considered this set of reforms. The last forty years are littered with failed federal education reform proposals at the K-12 level.

The better course is to end accreditation monopolies insofar as federal government is involved. Conservatives should push the federal government to remove itself as much as possible from higher education in all respects. The Left made a conscious effort in the 1970s to take over higher education and they’ve had a great time on campus ever since then, often at the expense of our nation and our culture. Much of what happens on campus is possible because of state and federal funding. It’s time to pull the plug.

If we can’t end federal student loans, they should be given at market rates of interest, with the recipient institution also on the hook for partial repayment under certain conditions—if an untoward number of your graduates regularly fail to enter full time employment and live independently of government assistance, for instance. Degrees that prepare no student for anything besides activism, i.e., gender and ethnic studies departments, would then become a net drain on a school’s resources. A solid liberal arts department might become the most practical part of campus. If its graduates can write well, speak articulately, and comprehend large doses of complex information, they’re employable.

Education and American Purpose

DeMuth ends by highlighting the biggest lie in American politics. Federal entitlement spending is unsustainable, and we can’t keep it going, but no politician wants to confront the lie that we can. (Well, Paul Ryan did, but….) I agree with DeMuth completely, but I also note that nationalist conservatism has made a commitment to entitlement spending part of its appeal. DeMuth’s point is well taken: come the crisis that destroys the lie and our public finances, we will have to pay for the entitlement state in a much different fashion than the debt-finance method we have used for so long.

That collective responsibility in the midst of crisis may do more to revitalize our obligations to each other and to the country than anything else. Suffering tends to be clarifying.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The national education reform the Right should advance protects and respects the American people.

Deliberation can deliver the nationalism we need.

What the anti-Madisonians wrought.

Our moralizing modern-day aristocrats are at odds with American justice.

Fire the bureaucrats and break the Left’s grip on education—or keep losing.