A proper national politics naturally protects both our shared prerogatives and our individual rights.

Schooling Choice

The national education reform the Right should advance protects and respects the American people.

Chris DeMuth’s brilliant treatise on “Trumpism, Nationalism, and Conservatism” has much to say about the state of America society, politics, and government. But it also has particular resonance when it comes to the field I know best: education. When we look to schooling, there is much that affirms DeMuth’s incisive analysis—together with some intriguing complications.

DeMuth traces our current dysfunction to the excesses of the administrative state and the way this shift has favored the cosmopolitan Anywheres while marginalizing the working class Somewheres. This has helped fuel the disaffection that has powered Trump and the populist moment. While DeMuth’s measured prose accepts the legitimacy of both the Anywhere and Somewhere worldviews, it’s clear that the Anywheres have been the aggressors, and also that DeMuth is unconvinced by the Anywheres’ claims to know what’s good, right, and in the best interests of the unwashed Somewheres.

That resonates when it comes to K-12 reform, especially when it comes to the conflicts between the nation’s Anywhere “reformers” and the provincial Somewheres—whose schools the reformers are out to “fix.” Indeed, DeMuth’s tale is almost a pitch-perfect synopsis, for instance, of the Common Core clash that burned so hot in the Obama years, when the foundation-funded, coastal Anywheres took it on themselves to fix reading and math standards—only to be met with ferocious opposition from right-wing Somewhere moms and left-wing Somewhere anti-testers.

But what makes the tale of K-12 reform in recent years so intriguing is that, aside from that episode, culturally progressive Anywhere reformers have generally been embraced by conservatives. How progressive are these Anywheres? Well, earlier this year, a new AEI study documented that political giving by the staff at more than 200 school reform organizations runs Democratic by better than a nine-to-one margin (the same ratio seen in famously liberal precincts like Hollywood or the public employee unions).

And yet conservatives have staunchly supported these Anywhere progressives—mostly because the reformers supported charter schools and criticized teacher unions. In fact, to appease their progressive allies, conservative reformers have made a wealth of concessions. They have accepted a massive increase in federal authority, an expansion of race-conscious accountability systems, and a general prohibition on talk of parental responsibility and the virtues of the traditional family. It’s a peculiar state of affairs, one largely motivated by a desire to placate Democratic allies willing to help advance school choice.

This raises a big question: How much should school choice continue to frame the right’s educational vision as it seeks a nationalist-conservative fusion? DeMuth urges a national agenda emphasizing “school choice” and “charter schools” because it “would address the interests of the Party’s Somewhere constituents and aim to garner new constituents from poorer and minority communities.” He is certainly right that school choice resonates with left-leaning Somewheres in poorer urban and minority communities. Where things get dicier, though, is when DeMuth suggests that school choice is broadly appealing for right-leaning Somewheres in the suburbs, small towns, and red America.

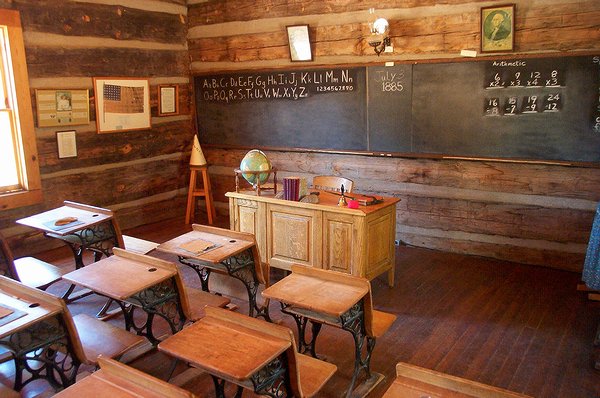

It turns out that, for much of the Somewhere right, school choice is an answer in search of a problem. In many small towns, communities, and suburbs, reformers don’t get very far when they celebrate “disruption” and denounce “zip-code education.” Indeed, 70 percent of American families historically give their kids’ schools an “A” or a “B.” The vast majority of the nation’s 14,000 districts are defined by intensely personal relationships, with two-thirds enrolling fewer than 2,500 students.

Across these communities, the “zip-code-based” schools that reformers decry are cherished hubs of local identity. This can be true even when outsiders look at test scores and dismiss schools as failures or “drop-out” factories. Locally, high school teams are sources of pride and anchors of routine. Geographic school communities can make it easier for children to make friends who live nearby and for parents to know their neighbors. Put in terms that should resonate on the right, local schools are engines of social capital that help to forge communities.

What school choice advocates see as an attack on bureaucracy and the administrative state (which is true in places like New York and Chicago) is experienced in many non-urban locales as an attack on their community and the educators they like. This is why many right-leaning Somewheres regard school choice with suspicion.

Choice-based reform has compelling virtues, which is why I’ve championed it since the last century. But the truth is that school choice works best in dense urban communities, where the need is clearest, the logistics at their most manageable, and the disruptions minimized. These are deep blue locales. This may be a great strategy for wooing Democratic constituencies, but if we take seriously DeMuth’s call to imagine a post-Trump right that incorporates the nationalist and populist Somewheres, an education agenda framed by school choice (and vocational education) is wholly inadequate.

So, what should our agenda look like?

First, the right should continue to unapologetically embrace the liberating, empowering power of choice—for families and educators. But we must also do much better at appreciating why school choice can seem irrelevant or even threatening to many in the nation’s small towns, rural communities, and suburbs.

This means respecting concerns about “disruption,” for instance, by approaching school closures as regrettable, not a bloodless byproduct of market competition. It means listening to, and not ridiculing, suburban parents concerned about how school choice might impact their schools. It means conceding that school choice may be a poor answer for communities where the next-closest junior high is 20 or 30 miles away. And, perhaps most importantly, it requires talking about versions of choice—like education savings accounts or “course choice” programs—that address practical concerns by giving families more access to good educational offerings, even when they have no desire to ship a kid off to a new school.

Second, in the past two decades, conservative education reformers have evinced less and less appetite for values-laden debates. Quite simply, this is nuts: schools are central to a healthy republic precisely because they embody, signal, and instill our societal values. As progressives have pushed schools to embrace identity politics, dismiss discipline as racist, take the left’s side in complex debates over gender and immigration, apologize for American history, and erase even the faintest vestiges of faith, the conservative policy community has stood largely silent. Pushback has been left to Fox News personalities and right-wing pundits.

This faintness of heart has, not surprisingly, driven a growing wedge between right-leaning Somewheres and the right’s school reform impresarios. Support of choice must be coupled with attention to communities and values, and a commitment to schools that embrace our common heritage, instill personal responsibility and responsible citizenship, celebrate America’s virtues and heroes, prize patriotism, make room for faith, and reject grievance politics.

As I said, education seems in many ways a microcosm of DeMuth’s analysis. As we’re often reminded, Trump may be unprincipled and ineffectual but, for better or worse, he’s a fighter—one who’s unapologetically on the side of the Somewheres and doesn’t shrink from clashes over culture. At least when it comes to schooling, it’s fair to say that conservatism sorely needs some of that.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Our federal and academic bureaucracies have had it too good for too long.

Deliberation can deliver the nationalism we need.

What the anti-Madisonians wrought.

Our moralizing modern-day aristocrats are at odds with American justice.

Fire the bureaucrats and break the Left’s grip on education—or keep losing.