A proper national politics naturally protects both our shared prerogatives and our individual rights.

Separated Powers, Fractured Nationalism

What the anti-Madisonians wrought.

Chris DeMuth’s excellent essay is a high point in the nationalist moment we’re enjoying. But that makes it necessary to understand just what nationalism might mean.

The Two Kinds of Nationalism

Nationalism comes in two flavors. In what might be called vertical nationalism, people desire their nation’s glory and preeminence over that of other countries. Vertical nationalism can be benign when it champions the superiority of French culture or German philosophy, for example. But it can be dangerous when it seeks glory and preeminence uber alles and hugs itself in self-delight because its weapons can reduce every other country to rubble.

Horizontal nationalism is quite different. Free from the jingoism that disfigures vertical nationalism, it rests on a sense of kinship to and solidarity with one’s fellow citizens. The horizontal nationalist seeks to create an economy with jobs for those who can work and a generous social welfare net for those who can’t.

Throughout American history, Republicans have been the party of vertical nationalism and Democrats the party of horizontal nationalism. Republicans wanted America to possess the biggest military in the world—and they got it. But they found horizontal nationalism in conflict with their creed of individualism. They left horizontal nationalism to the Democrats and leaders like FDR who effectively communicated a sense they cared about all Americans—a feeling one didn’t quite get from Mitt Romney.

The 2016 election was remarkable because, almost for the first time, a Republican presidential candidate ran on a platform that united nationalism’s two strands. Trump wasn’t going to gut entitlements, despite how much his party’s establishment might have wished him to do so. And he promised that we’d not just repeal Obamacare—we’d repeal it and replace it with something beautiful.

Trump found the sweet spot in American politics: the place where presidential elections are won. He campaigned on social conservatism and economic liberalism with a slogan that implied both vertical and horizontal nationalism.

Why have America’s neo-nationalists failed to understand this? In some cases, it’s because they are simply right-wingers—like Romney, and unlike Trump.

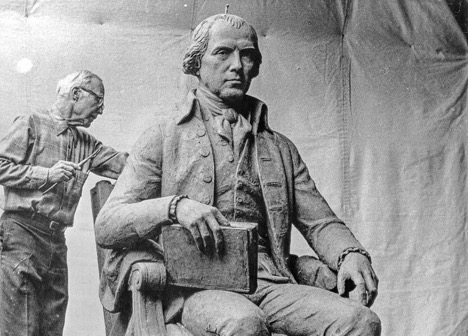

America Doesn’t Have A Madisonian Constitution

Things would have turned out differently if we’d had a Madisonian constitution. What James Madison wanted, in his Virginia Plan, was a lower house elected directly by the people, with the number of representatives in each state based on population. The upper house and the executive would have been selected by the lower house. A federal right to disallow state laws was thrown in for good measure. When Madison failed to get this, he was so disappointed that he proposed a walk-out from the Convention on July 17, 1787.

The American Constitution isn’t Madisonian. Call it Shermanesque, after Roger Sherman, if you want. Or Morrisian, after Gouverneur Morris, the sharpest of the delegates in Philadelphia that summer. If you’re looking for a Madisonian Constitution, look north instead.

Under the Canadian constitution, M.P.s are elected by voters in their districts, with representation based on population. The M.P.s in the winning party choose the Prime Minister, who then appoints members of a toothless upper house. The Canadian federal Prime Minister also enjoys Madison’s “national veto”—the power to disallow provincial legislation.

This is why Canadian conservatives are more likely to be horizontal conservatives. Tory party leaders in Canada and Britain understand nationalism’s gravitational pull towards left of center economic policies and embraced horizontal nationalism from the start. That was how Benjamin Disraeli broke with Sir Robert Peel over the Corn Laws, and how Sir John A. MacDonald’s National Policy dished the Manchester Liberals in the opposition. As Tories, Anglo-Canadian conservatives are vertical nationalists; as Red Tories, they are horizontal nationalists. If you want to understand 2016, learn from them.

Crucially, a Canadian Prime Minister can enforce his policies by sending in the Whips and threatening to expel dissenting M.P.s. That’s a luxury American presidents lack. Much as Trump might have wished it otherwise, he was stuck with Paul Ryan, John McCain, and the separation of powers.

The Two Republican Parties

In a parliamentary system, all politics is national; while in America, all politics is local.

And so there are two Republican Parties: A presidential one that is nationalistic in the horizontal sense, and a congressional one that isn’t. Given the structure of the American Constitution, I don’t see that changing.

In particular, calls for Congress to assume its “proper constitutional role” seem unlikely to go anywhere. You don’t tell businessmen how to make money, and you don’t tell politicians how to win votes.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

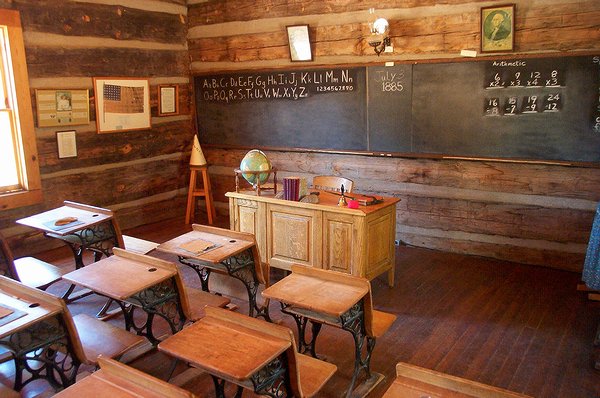

The national education reform the Right should advance protects and respects the American people.

Our federal and academic bureaucracies have had it too good for too long.

Deliberation can deliver the nationalism we need.

Our moralizing modern-day aristocrats are at odds with American justice.

Fire the bureaucrats and break the Left’s grip on education—or keep losing.