Our new technological environment is inescapable, as are the threats it poses.

Love Can’t Be Uploaded

Our human need for connection should keep us grounded in reality.

This feature presents responses to an excerpt from Claremont Institute Executive Editor James Poulos’s forthcoming book Human, Forever: the Digital Politics of Spiritual War. Sign up at humanforever.us to be the first to know when Human, Forever NFTs and sales go live on canonic.xyz.

Ah, love.

As long as mankind has been kicking around, we’ve been trying our damndest to put a finger on why we crave it more than anything else this side of heaven. The poets and bards have had a few ideas. But love, particularly the romantic sort, is elusive, tough to encapsulate in language, an entity without measure or full understanding. It causes us to yearn, to weep, to know the most punishing hurt. It grants us joy at its highest height and forgiveness in its deepest form. It’s not always a comfortable thing—it generally isn’t. As the notoriously practical romantic Jane Austen put it: To love is “to burn, to be on fire.” Indeed, burning isn’t the easiest mode of existence, but throughout most of history, we’ve been able to agree that it’s worth it. For, as a certain French musical reminds audiences every day, love allows us to see, in another, the face of God Himself.

It seems those poets were onto something. For everything else that it is, to love is to be fully alive. In love, we are our most utterly real. But today, in our digital world, we’re watching love fade. And, for that, we can thank the preponderance of ease.

James Poulos’s new book Human, Forever, sheds some light on why this is the case. As humans, we’re meant to experience reality as it is without distortion. But we are increasingly—and soon, entirely—operating in an augmented, comfortable world that we’ve convinced ourselves is good enough for us. This is fundamentally changing us.

In romance, that shift seemed to happen overnight. Within a breathtakingly short amount of time, the wooing of a partner careened from letters and flowers and walks in the park to getting the stupid cadence of an online conversation just right. From being awestruck by a face in the crowd to swiping right. From the hope for forever to the hope for just one pleasurable night.

For the hopeless romantic, things seem fairly hopeless.

This wasn’t an overnight phenomenon: we simply didn’t see it coming. But in hindsight, we shouldn’t have been surprised. Long before dating apps came the digital, a lens through which humanity thought we’d achieve new heights. In the digital world, any action, formerly affecting those around us, could be simultaneously further-reaching and less consequential. In short, we convinced ourselves that action became better, simply because it became easier.

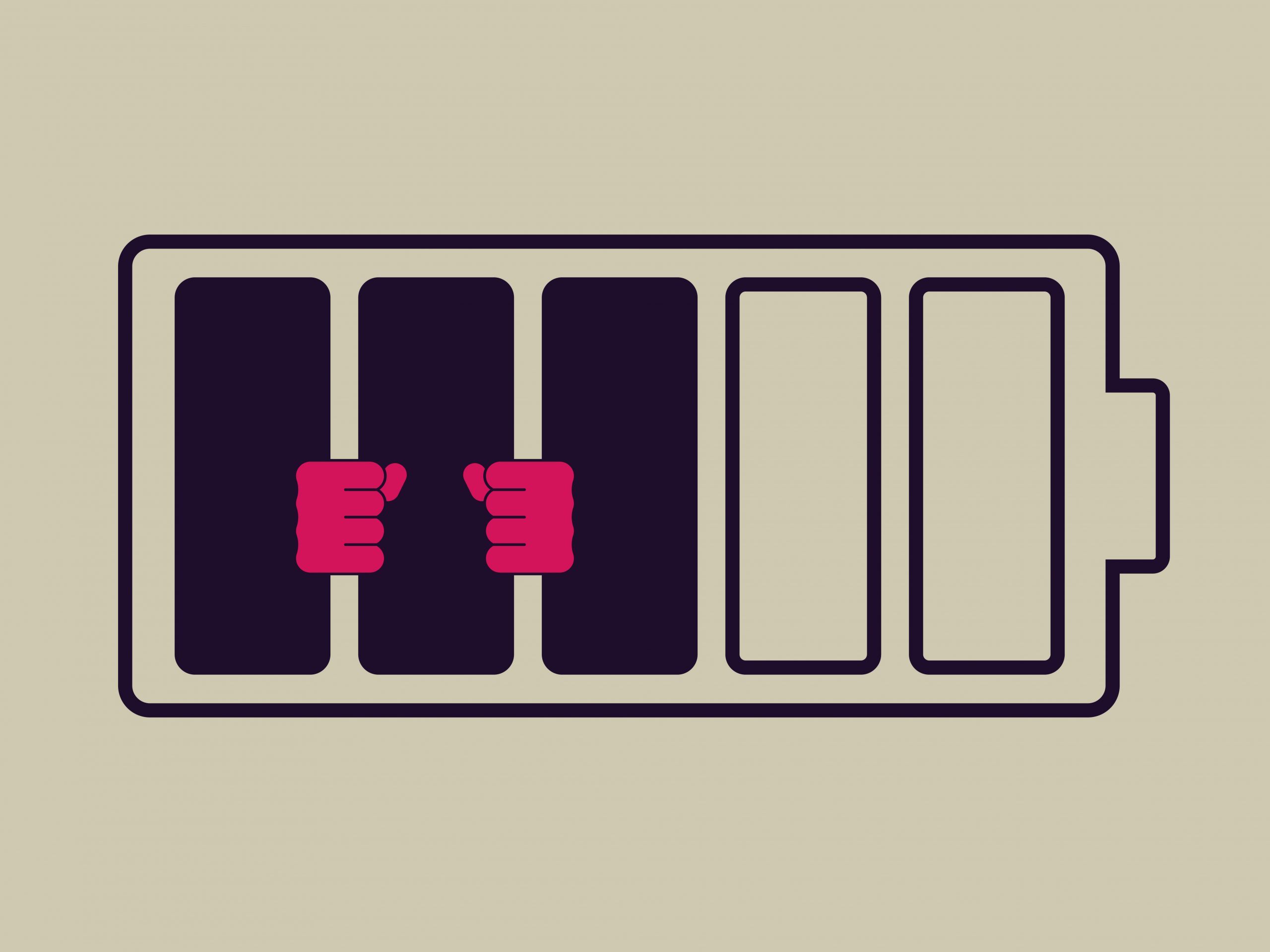

Yet ease can be tyrannical, and it’s since proven itself to be so. Indeed, comfort is addictive. Too much of it is murderous to the human soul. Just as the human body becomes lethargic and distorted without any semblance of struggle, so, too, does the heart long for toil, for the striving that makes reward taste so sweet.

The shackles of ease restrict no persons more than they restrict men. By consequence, however, women are also chained. In the end, romance as an ideal is destructively disenchanted.

IRL

We all feel it. Ask any single woman who’s not deluding herself whether she’s happy with her dating life. The answer, likely, will be a resounding “no.” Beautiful or plain, funny or boring, clever or dopey—it doesn’t really matter. Women everywhere are feeling the natural pains of being no one’s prize.

But the male instinct for pursuit and struggle, for the hand of a lady or to stand for what’s right, hasn’t been killed (God, in His mercy, still endows men at birth with a man’s nature). No, much like the human instinct for anything—friendship, work, social justice, or even dinner—it’s merely been rerouted to the unreal.

Today’s boys and men have learned to be sated by the online gamification of what were once true and essential challenges that bolstered the masculine spirit. We see it in every aspect of the man’s life. In vocation, working with one’s hands is a thing of the past. Liberal arts degrees and the rise of the computer age have seen to it that men no longer feel the need for hard skills—their softer, more feminine abilities will do far more to win them bigger bank accounts in the white-collar world. In friendship, many men have even lost the ability to forge meaningful bonds (a daunting task in the modern age), and they suffer as a result.

Even down to the minutiae, men have been soothed by the need to do nothing. Quick, bold, physical movements—like reloading a gun, changing a tire, or perfecting a left hook—have been relegated to a couple of deft button pushes on a video game. Sports, the last vestige of physical battle in the disenchanted fake world the decadent have created, can be played vicariously on a PlayStation or through aptly-deemed “fantasy” leagues. It’s all so easy.

No wonder asking a real-life woman out seems like too much work. No wonder women feel the need to be on dating apps if they ever hope to have a kid or two. No wonder women, tired of waiting on men to become their counterparts, are more and more frequently looking to one another for romantic comfort. No wonder romance between men and women feels like it’s drawing its last ragged breath. We’ve sacrificed the ideal for the practical. For the digital. For the easy.

Indeed, the ideal is shriveling each day in favor of comfort. Monogamy, another word for commitment (no easy feat), is becoming less popular. Young people are abandoning marriage as an institution in droves—a fourth of the millennial generation is unlikely to ever marry—and those that do are increasingly signing prenups in case things don’t work out.

It’s devastating. Not only to the heart and soul that longs to be loved but also to our future as humans. The end of romance also means the fast decline of reproduction—another difficult thing we’re anxious to escape with birth control, rampant abortions, and artificial wombs.

That’s no joke. As Lyman Stone pointed out at American Compass, “falling fertility will have numerous consequences for societies all around the world. Slower population growth will lead to rising inequality, growing prominence of inherited wealth, increasing monopoly power by existing firms, and a decline in entrepreneurship and innovation. Demand for new housing will stagnate. Intergenerational transfer programs like Social Security (or private life insurance, or even the stock market) will face financial troubles. Interest rates and inflation will stay preternaturally low, limiting options for recession-fighting and making every recovery slower than the one before it. Debates about immigration will become ever-more-rancorous.”

It’s a sad future, and one we shouldn’t shrug off as yet another symptom of wretched modernity. The struggle for love is the struggle for life, and to sacrifice it to the gods of digitization is suicide.

Fortunately, as Poulos’ new book aptly points out, the human spirit cannot be so readily quashed. Many of us, opening our eyes to the dullness of the technological world, are eager to reclaim a new, natural, and good life. We’re beginning to feel weary of screens and ease—we want what’s real, true, and essential while we’re on this mortal coil. What’s left for those of us who understand the disease is to point to the antidote: real, true love.

The silver lining will always be this hope: No matter how hard they try, the devils among us anxious to strip us of our humanity cannot replicate love. They can make cheap imitations of it. They can give us sex robots to quell our need for physical affection and they can insist that marriage is a scam. They might even succeed in somewhat convincing most of us young people that they’re right.

But I can say for certain that nothing has ever made me feel the way I do when I see my man smile from ear to ear. No lengthy digital conversation has ever caused my heart to soar quite so high as when he hands me the wildflowers he plucked on the walk to my house. Aside from my relationship with the Good Lord and allegiance to His Church, nothing has ever made me feel more genuinely alive, even in tears and sorrow. This real love, if I’m lucky, will be my highest happiness for all of my days. No digital imitation could ever come close.

I’m not the only one. Plenty of young people are already stirring from the waking slumber the fake world has put us under. And, what’s more, every human being has the innate potential for deep, meaningful love, the kind that achieves the ideal the digital is trying so desperately to kill. We shouldn’t let it—romance is too precious a thing to let it die at the hand of ease. We should fight back, because so much depends on our success.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Americans should resist technological subjugation by any means necessary.

Our unruly digital environs are frightening, but they’re better than total bureaucratized control.

A cloud of soulless bots has devoured our grandest dreams. How do we live now?