Restoring trust in America’s constitutional system will require some deference on the part of SCOTUS.

Who is a Person?

After Roe, America will face a fundamental question.

No one should be surprised by Justice Alito’s leaked opinion overruling Roe v. Wade. Sensible observers have long known that this infamous decision created an untenable “right to abortion,” one that was ripe to be repudiated or overruled by a future court. The real surprise will be what happens next. Like previous legal decisions from the era of slavery, Roe touches upon a question foundational to our constitutional order: what is a person? Significantly, it is not a question that can be answered piecemeal or by half measures. States will have to decide it one way or another.

As most scholars (on both sides) confess, the Roe decision was a judicial fiat. The Court spoke a new “right to abortion” into existence. Fifty years later, no judge, lawyer, or serious legal scholar now believes that Roe correctly articulated a constitutional right. And Justice Alito’s leaked opinion gives voice to what is now the commonplace method of identifying our constitutional rights.

Justice Alito explains two standards for identifying rights not expressly identified in the text of the Constitution: these “unenumerated” rights must be either “implicit in the constitutional text” (the freedom of association is implicit in the right to assemble, for example) or “deeply rooted in our Nation’s history and traditions” (such as the right to direct the upbringing of one’s own children).

These standards were designed precisely to ward off claims of illegitimacy. As Justice Byron White observed in 1986, “The Court is most vulnerable and comes nearest to illegitimacy when it deals with judge-made constitutional law having little or no cognizable roots in the language or the design of the Constitution.” While these standards are not perfect, they should at the very least place some limits on the Court’s ability to declare new rights by fiat.

Roe blew past these stop signs on the way to declaring a right to abortion. As Justice Alito explained, “Roe…was remarkably loose in its treatment of the constitutional text. It held that the abortion right, which is not mentioned in the Constitution, is part of a right to privacy, which is also not mentioned.” And unencumbered abortion is certainly not deeply rooted in American history or traditions.

In the common law, abortion was criminal during at least some stages of pregnancy for centuries. Common law treatises going back to at least the 17th century describe abortion of a “childe” as a “heinous offense,” a “great crime,” and “homicide or manslaughter.” In statutory law, abortion “had long been a crime in every single State.” Justice Alito’s opinion comprehensively details the history of abortion in America and lays to rest any notion that history supports such a practice. As Justice Kavanaugh said at the oral argument on December 1, “[t]he Constitution’s neither pro-life or pro-choice on the question of abortion but leaves the issue for the people of the states or perhaps Congress to resolve in the democratic process.”

So much for the “right” to an abortion—if the final decision of Dobbs reflects Alito’s draft, then Roe’s demise is a fait accompli. But the abortion issue is not over.

After Dobbs, states will indeed diverge on their treatment of the issue. As it stands now, over half of the states are poised to impose significant abortion restrictions, including outright bans. Other states will expand abortion rights, as New York recently did, or position themselves as “havens” for abortion. Congress and President Biden have both pledged to expand abortion rights nationwide. Even private companies are getting in the mix, such as Amazon, which pledges to pay for U.S. employees who travel for abortions.

While policymakers will be off to the races setting their own abortion policies, overturning Roe raises a lingering question exposed by the very “deeply rooted history and tradition” standard that undermines Roe in the first place.

Consider this: Wisconsin’s 1849 state law, as a typical example, referred to the unborn as “individuals” with both “lives” and “persons.” The law banned the “killing of an unborn quick child,” and prohibited the use of any instrument “with the intent to destroy such child.” Virginia likewise banned the use of an instrument to “destroy the child.” Missouri, Illinois, Vermont, and Massachusetts prohibited the administration of any poison or other substance to cause the miscarriage of any woman “being with child.” Several states specifically mentioned higher penalties when the abortion caused the death of a “quick child.”

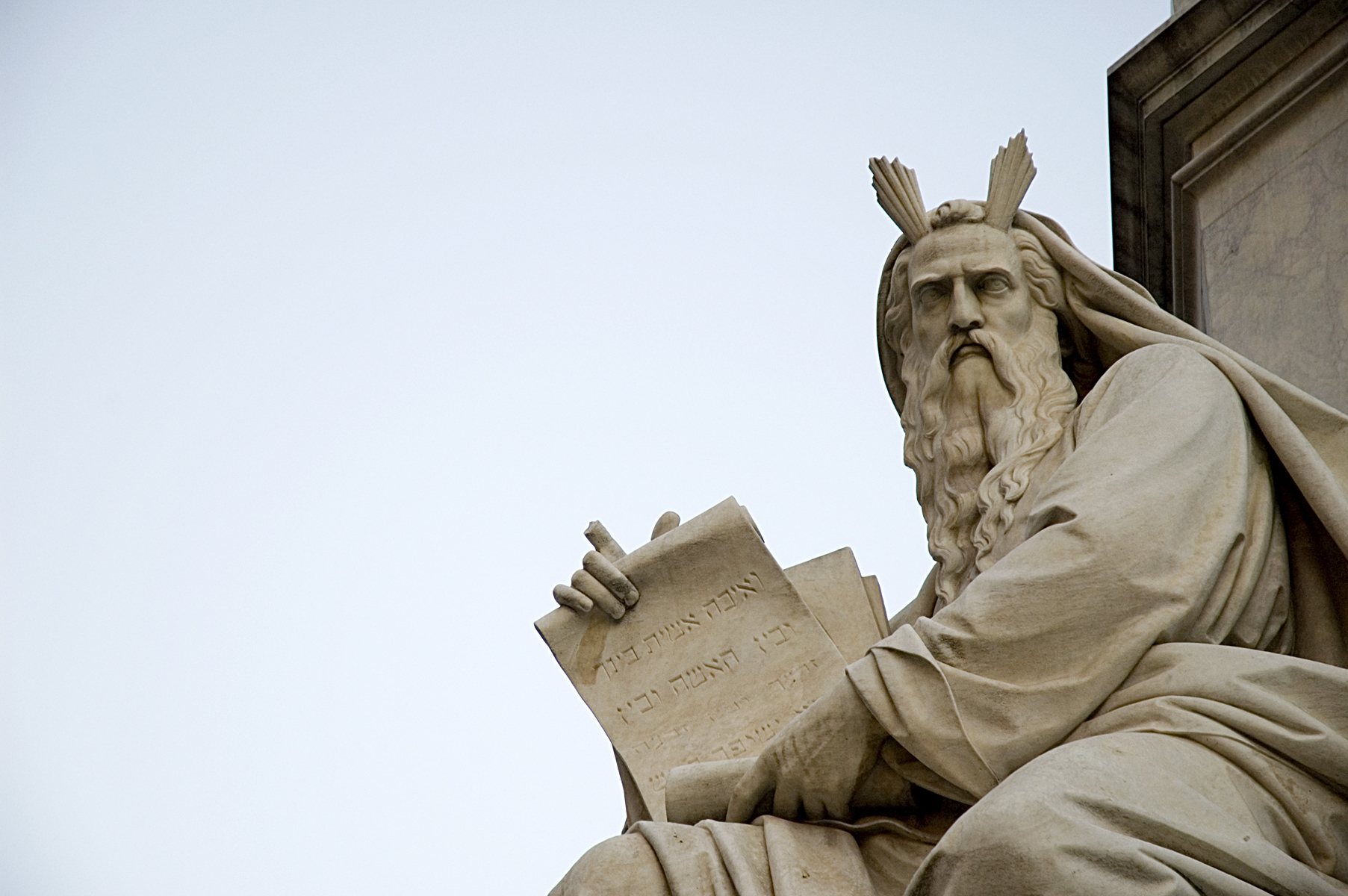

The deeply rooted history and tradition of America, therefore, identifies the unborn as “individuals” and “child[ren],” with “lives.” They are, in the words of Wisconsin’s statutes, “persons.”

The rights that the Constitution protects are, according to the text, those of “persons” and “citizens.” States similarly refer to the inherent and God-given rights of “persons” and all “people.” As typical examples, the Michigan Constitution establishes that “no person shall be denied the equal protection of the laws,” and the Wisconsin Constitution guarantees the rights of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” for “all people.” If the unborn are persons, and persons have rights protected by the Constitution, then it follows that the unborn have constitutional rights just like any “born” person.

The legal notion of a “person” is not coterminous with that of a “human being”—corporations, for instance, are legal persons, meaning that they can bear rights and duties even though they are abstract entities and not individuals or “natural persons.” But at the very least, if something is a human being, it is a person. In the case of abortion, then, if not elsewhere, the question whether unborn babies are persons boils down to whether they are human beings—whether they are the “men,” i.e., the humans, spoken of in our Declaration of Independence as endowed with the inalienable right to life.

Thus “personhood” is not some academic minutia. It is a question with real and serious consequences. In fact, the issue of “personhood” is not new. It’s been lurking in the shadows of Roe itself, which posited, “[if] personhood is established, the appellant’s case, of course, collapses, for the fetus’ right to life would then be guaranteed specifically by the Amendment.” After a few brief sentences, Roe dismissed further discussion of that argument, finding “that the word ‘person,’ as used in the Fourteenth Amendment, does not include the unborn.” Critically, the Court acknowledged that its terse conclusion “does not of itself fully answer” the question of personhood.

Justice Alito’s leaked opinion endorses the idea that constitutional rights (or in his words, “legal protections”) attach the moment someone can be described as a “person.” Explaining why it is difficult to draw the line of personhood, Justice Alito notes that some philosophers say personhood attaches upon “sentience, self-awareness, the ability to reason, or some combination thereof.” But “by this logic,” Justice Alito continues, “it would be an open question whether even born individuals, including young children or those afflicted with certain development or medical conditions, merits protections as ‘persons.’” Indeed, all “persons” “merit protections.”

And so after Roe, while states scramble to adjust their policies, and the federal government attempts to flex its power, Justice Alito’s opinion will produce a question that abides. Are the unborn “persons” entitled to full constitutional protections?

That is a question worth answering, and one that America should be bold enough to confront. The issue of whose rights are protected by the Constitution is (or should be) foundational. This issue may come to a head in states that are generally considered “pro-life,” yet have other laws supporting abortion. Wisconsin, which has its own criminal ban on abortion, also requires county health departments to support minors seeking abortions. If the unborn are persons, then the government would have to justify its support for women seeking abortions (presumably in other states).

To be sure, personhood is fraught with difficult “whataboutisms”: What about common exceptions such as life, health, rape, and incest? What may a state permit, and what must a state prohibit under the doctrine of personhood? Could abortion ever be legal if the unborn are persons entitled to full constitutional protections? But before those questions are even raised, the fundamental question at issue will be whether the interests being weighed are those of two persons—mother and child—or those of a person (the mother) and a nonentity. The unborn child is either a person, or it is not. There can be no in-between.

Because of Roe, America hasn’t had to answer these difficult questions. A constitutional right to abortion allowed us to turn a blind eye to the legal status of the unborn. But now our time is up, and we must, as a nation, answer the most fundamental question posed to any civil society: what is a person? If the unborn are persons and equally as worthy of protection as the born, then we must say so definitively and adjust our laws accordingly. It is truly a matter of life and death.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Pro-abortion reactions to the Dobbs leak reveal idolatry for what it is.

How natural law limits state power.

The Constitution cannot, and should not, be twisted to favor abortion.

Are we ready for life after Roe?

The case for abortion falls apart.