Restoring trust in America’s constitutional system will require some deference on the part of SCOTUS.

Leaving Omelas

Are we ready for life after Roe?

In “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” Ursula K. Le Guin tells of the perfect city. There’s no violence, poverty, or guilt. There’s only joy—except for one thing.

There’s a young child, locked in a room. The child spends its days alone, sitting in filth and misery, its cries for help ignored. But the child’s suffering secures all that is good in the city—and the residents know it: “If the child were brought up into the sunlight out of that vile place, if it were cleaned and fed and comforted, that would be a good thing, indeed; but…in that day and hour all the prosperity and beauty and delight of Omelas would wither and be destroyed.”

When it comes to abortion, America is a kind of Omelas. After the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade (1973), the Left’s reaction has been a mix of hysteria and despair. I can understand why. It’s an affront to the progressive project of life without limits. After the Sexual Revolution, sex wasn’t supposed to be a powerfully binding act of intimate love between two people anymore. It was merely a physical exchange, a “hook-up.” The emotional and psychological consequences of sex were eradicated.

Abortion made this freedom complete, which is how “you may not kill that baby in the womb” became interpreted as an attempt to control women’s bodies. Having a child imposes limits on a woman’s professional and personal choices. Abortion, therefore, is the last line of defense between a woman’s total control over her life and the world-changing event of having a child.

Abortion allowed sex without consequences—at least not the visible kind. You could live your life on your own terms. This practice was like the suffering child in Omelas. Millions of babies in the womb were poisoned or dismembered so that others could be happy and free from limitations. One woman who had an abortion for financial reasons described the blessings it produced: she and her partner are “now married with a new home and steady careers. That wouldn’t have happened with a kid.”

And like any convenient act of violence, abortion is justified in terms of material benefits. It lowers crime, say its defenders. It increases women in the workplace. It lessens the wealth gap between the sexes. It decreases poverty. It raises women’s educational attainment. Yet pro-lifers know the benefits are not worth the cost. No amount of wealth or freedom or safety or joy is worth killing innocent human life. The perfection of Omelas is not worth the child suffering in that miserable prison.

But are we prepared for what comes next? Are we ready, as Matthew Walther asks, to “trade the eradication of our way of life for the end of legalized infanticide?” Because what if banning abortion really does lead to fewer women in the workplace or college classes? What if educational attainment and incomes fall and crime increases? What if the blessings of abortion disappear?

We must be ready to help offset the costs. Government assistance isn’t the only solution— states that ban abortion should have a web of charities and churches ready to assist mothers and families. But government can sure help. More generous child allowances or child and dependent care tax credits would ease the burden on mothers. States can and should make adoption seamless and subsidized. Paid family-leave programs and part-time work opportunities can help accommodate mothers in the workplace.

In the post-Roe world, Red states’ holistic vision of life will be the deciding factor of public opinion. Protecting the unborn is important. But so is supporting mothers and families. Each state, with its combination of policies, will either attract more supporters or repel persuadable people. Communicating to mothers that we are with them through the uncertainty and the sacrifice is pivotal if we want to one day see an abortion-free America.

Overturning Roe forces a reconsideration. For 50 years, even the question of abortion has been walled off from debate. But now the walls have fallen. Public opinion is roughly split and hasn’t changed much over the years—but there’s reason for hope.

At the end of Le Guin’s story, we learn of a group of residents who, after seeing the miserable child, do not return to their homes. They leave the city. They walk away.

Those who previously overlooked the truth of abortion now have a chance to recognize it for what it is: the suffering infants securing happiness for the community. They too can walk away from Omelas. We must make it easier to leave.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

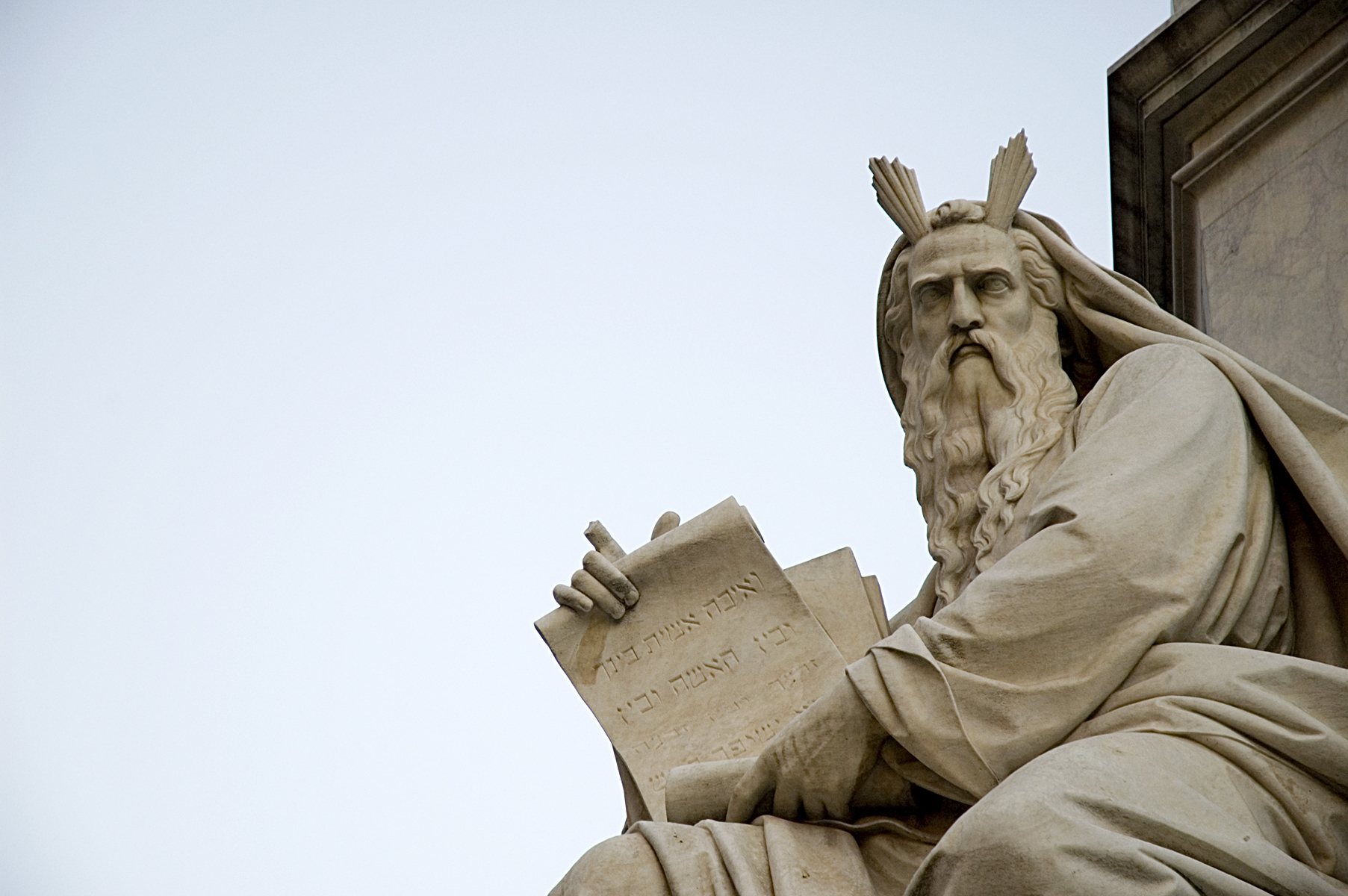

Pro-abortion reactions to the Dobbs leak reveal idolatry for what it is.

How natural law limits state power.

The Constitution cannot, and should not, be twisted to favor abortion.

After Roe, America will face a fundamental question.

The case for abortion falls apart.