Thanksgiving Wasn't Always a Source of National Unity.

I Think Therefore I Thank

We should be thankful for the sheer wonder of being.

“To think is to thank” is a saying used by figures as different as G. K. Chesterton, a cheery theist, and —of all people—Martin Heidegger, a dark existentialist. (Denken/Danken works in German, too). But the differences between what they each meant are stark and instructive.

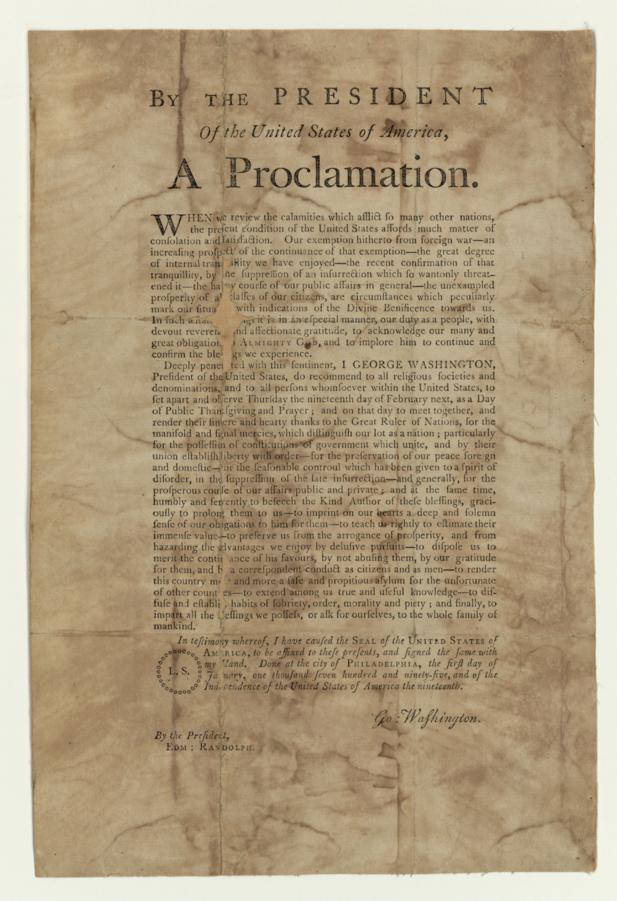

What GKC meant was clearly in line with the Pilgrims and Founding Fathers, who recognized the role of Divine Providence and nature’s God in human life on these shores, hence the first and subsequent Thanksgiving celebrations. Heidegger, a notoriously difficult thinker, seems to have meant that our very efforts to understand the world and our place in it, properly pursued without invocation of any god, is a kind of secular gratitude in its own right.

This division seems to be very close to the surface in America and most Western societies today. We still have many people with a kind of a natural piety, grateful to God or nature or at least for the good fortune of living in America. (The race-class-gender radicals who make the most noise in public and in institutions of higher learning should talk to someone in the whole caravans of people seeking entry here, who have shown with their feet that they don’t believe the United States is a bubbling cauldron of prejudice, exploitation, and repression.)

It’s a postmodern paradox that we have to think about it to realize how thankful we should be. Where material abundance on an unprecedented scale exists—as is now the case in all the developed societies—it’s difficult to see how extra-ordinary it all is. It seems ordinary to us, as if places that don’t enjoy the same material welfare are somehow almost inexplicable. It took not only divine Providence, but much human effort and no little sacrifice to get where we are: The sacrifices of workers and entrepreneurs, of slaves and scientists, of soldiers and sailors and airmen.

To think yourself into the proper attitude of thankfulness does not mean ignoring the costs and continuing consequences of such sacrifices, or ignoring the poverty of human and spiritual life that often enough accompanies material riches, or ignoring segments of society that don’t fully participate in our wealth.

But authentic nationalism means that gratitude for the good of our nation doesn’t conflict with other people feeling gratitude for their own.

Part of the proper gratitude in our circumstances is to make an effort so that the goods we enjoy do not eclipse the crucial human values—justice, generosity, and solidarity—that are always in danger of being overlooked.

That’s one set of our responsibilities. The other challenge, on the more existential side, is the creeping notion, which seems to gain momentum every day, that there are no such values. Many people who haven’t read and could never read someone like Heidegger, believe that we exist in a meaningless world where neither God nor nature offers any guide for our lives, and we decide—entirely on our own—what we choose to call true and good.

You can consider this, as Heidegger did, a kind of thanking, but to whom or to what? Many people today seem to be adrift precisely because they have no answer to that question.

Properly speaking, you cannot thank a thing. You may feel some sort of happiness that you and the world have come into existence, but that is not exactly the same thing as gratitude.

Gratitude proper is to persons, to someone who has done something good for us that they might not have. After all the intellectual pyrotechnics, a figure like Heidegger is proposing a gratitude that is gratuitous, because there is simply no one there to thank in the kind of thinking he employs. And he’s not the only one.

If we want to be thankful at all, we come back to the mysteries: God, nature, persons, communities, history, where things could have been very different. Our gratitude does not necessarily give us answers to important questions or solutions to mysteries. But in one way Heidegger was right: just to be in contact with such realities already raises up our existence.

On Thanksgiving, then, we remember with gratitude the many good things around us, but also the whole wonderfulness of being in the world, which Aristotle said was the beginning of philosophy. The Psalmist says the heavens declare the glory of God. It’s only when we see the one or the other that we become even remotely capable of thinking through what being thankful is all about.

Happy Thanksgiving.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

How Abraham Lincoln created Thanksgiving.

Thanksgiving remains one of our few unifying traditions.

The Genuinely American Debate over Federalism and Thanksgiving.

Allen Guelzo, Richard Brookhiser, Joseph Bottum, and Justin Dyer on the thought and action of Lincoln's Thanksgiving and his wrestling with God.

We must not ignore our extraordinary blessings.