Thanksgiving Wasn't Always a Source of National Unity.

We’re Living on the Plymouth Rock

May the spirit of the Pilgrims never fade.

Did the spirit of the Pilgrims fade after the Founding, only to be revived later?

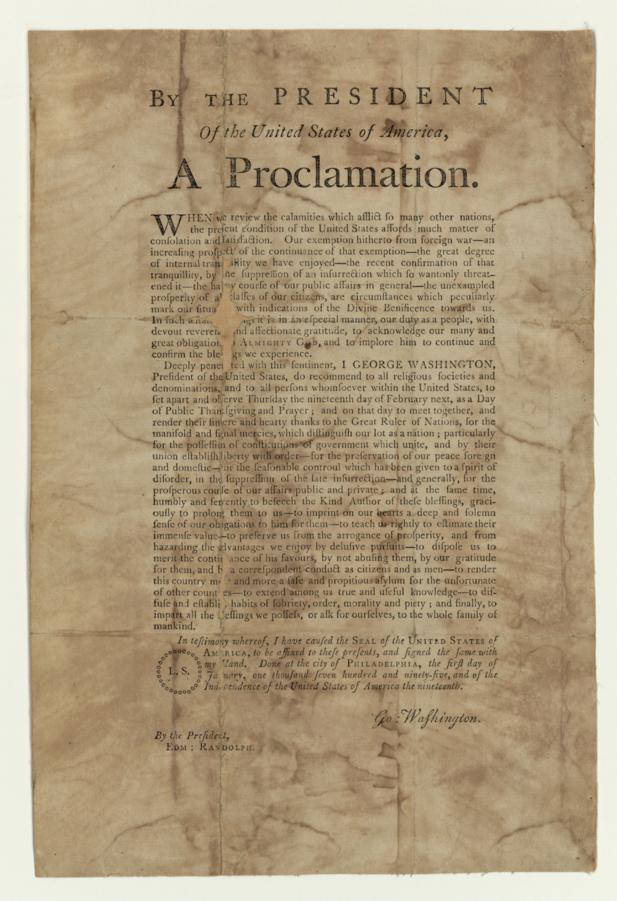

One might get that impression from the history of Thanksgiving as a holiday. Presidents Washington and Adams called for days of Thanksgiving, but it was not declared a National holiday and given a set date until Lincoln’s presidency in 1863.

Jefferson was downright opposed to days of Thanksgiving, discontinuing them in part because he wanted a strict separation of church and state. Jefferson was also personally opposed to the holiday because he was a deist: he hated all praise of a Providential God, of a God who was still involved in human affairs. He wanted to shut it down, even though it was cherished by his mostly Protestant fellow citizens. We might say that Thomas Jefferson was to Thanksgiving what the Grinch is to Christmas. And like the Grinch, Jefferson was unsuccessful in ending Thanksgiving celebrations. The holiday only increased in popularity. It’s really not true to say the spirit of the Pilgrims faded in the period between the Founding and Lincoln.

Let’s first look at the state and local laws passed about Thanksgiving during this period. Thomas G. West, in The Political Theory of the American Founding, argues that state and local laws often tell us more about the moral and political ideas of the period than national laws do. Beginning with New York in 1817, several states adopted Thanksgiving as an annual state holiday celebration. Beyond what was going on at the legal level, there were great cultural accolades— in books, newspapers, and speeches—for the Pilgrims and their stern godliness.

Daniel Webster, perhaps the period’s greatest orator, gave a speech in honor of “The First Settlement in New England” on December 22nd, 1820. The occasion was the 200th anniversary of the landing at Plymouth Rock—the rock stamped with “1620” near the landing site of the Mayflower in Massachusetts. The future Senator’s speech, sometimes known as the Plymouth Oration, is worth careful study. Webster’s oration not only helps fill a memory gap we might have about Thanksgiving between Washington and Lincoln, but is also a beautiful and powerful message.

Webster’s speech captures the Pilgrims’ influence on the American regime. Much like Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, Webster includes evocative imagery of the rocky land and blustery New England weather:

“We cast our eyes abroad on the ocean, and we see where the little bark, with the interesting group upon its deck, made its slow progress to the shore. We look around us, and behold the hills and promontories where the anxious eyes of our fathers first saw the places of habitation and rest. We feel the cold which benumbed, and listen to the winds which pierced them. Beneath us is the Rock, on which New England received the feet of the Pilgrims.”

Webster extols the virtues of several Pilgrims, the memory of whom was, in a real sense, the America’s true rock and foundation. He highlights “the mild dignity of CARVER and BRADFORD, the decisive and soldierlike manner of STANDISH; the devout BREWSTER; the enterprising ALLTERTON.” Like Lincoln in his First Inaugural, Webster draws a chord of memory between the heroes of Plymouth Rock and liberty-loving Americans of his own day. Webster’s practical, timely purpose was to argue against slavery’s spread. He argues that the Pilgrim Fathers would want the people of Webster’s day to oppose slavery or stop celebrating the memory of their Pilgrim forebearers:

“If there be, within the extent of our knowledge or influence, any participation in this traffic [in slavery], let us pledge ourselves here, upon the rock of Plymouth, to extirpate and destroy it. It is not fit that the land of the Pilgrims should bear the shame longer… Let that spot be purified, or let it cease to be of New England.”

The Pilgrims would have disdained a surface gestures of respect, if the actions of the people who made those gestures were morally deficient. Webster’s message for us today is contained in his concluding valediction dedicated to future Americans. His wish is that we would be welcomed into “the immeasurable blessings of rational existence, the immortal hope of Christianity, and the light of everlasting truth.”

Webster hoped that the spirit of the Pilgrims would never fade. He hoped that the tradition of America as a “City on a Hill,” an exemplar of Christian virtue in a world of darkness, would continue. He surely would have been pleased that a future President named Abraham Lincoln, the great emancipator, would dedicate a portion of November to a celebration of Thanksgiving to God for his many blessings.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

How Abraham Lincoln created Thanksgiving.

Thanksgiving remains one of our few unifying traditions.

We should be thankful for the sheer wonder of being.

The Genuinely American Debate over Federalism and Thanksgiving.

Allen Guelzo, Richard Brookhiser, Joseph Bottum, and Justin Dyer on the thought and action of Lincoln's Thanksgiving and his wrestling with God.