Thanksgiving Wasn't Always a Source of National Unity.

The Thanksgiving Wars

The Genuinely American Debate over Federalism and Thanksgiving.

In an era known for its political polarization and conflict, Thanksgiving is viewed by most Americans as a time of respite—for reconnecting with friends and family, and to be thankful for things simple and great. This was not always so. In fact, before becoming a national holiday with President Abraham Lincoln’s Proclamation on October 3, 1863, the call for a national day of thanksgiving was fraught with fundamental arguments about federalism, religious liberty, and the role of government.

Appropriately, George Washington was the first American president to issue a proclamation calling for a “Day of National Thanksgiving” on October 3, 1789. The birth of a new nation with a ratified Constitution is much to be thankful for, after all, and Washington pronounced Thursday, November 26th of that year, “be devoted by the people of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being who is the beneficent author of all the good that was, is or will be.” Portending deeper future political battles, a debate ensued in Congress over whether the federal government should issue such national proclamations. This one broke along Federalist/Anti-Federalist lines. South Carolina Representative Thomas Tudor Tucker argued that “the House had no business to interfere in a matter which did not concern them,” asking, “Why should the President direct the people to do what, perhaps, they have no mind to do?”

The Federalists and Washington won the day (thankfully) with the President following the Proclamation with a donation of $25.00 designated to the Presbyterian churches in New York City (remember, the national capital was in Lower Manhattan at this time), which was “to be applied towards relieving the poor”, per the letter drawn by Washington’s secretary, Tobias Lear. Washington put his money where his proclamation was.

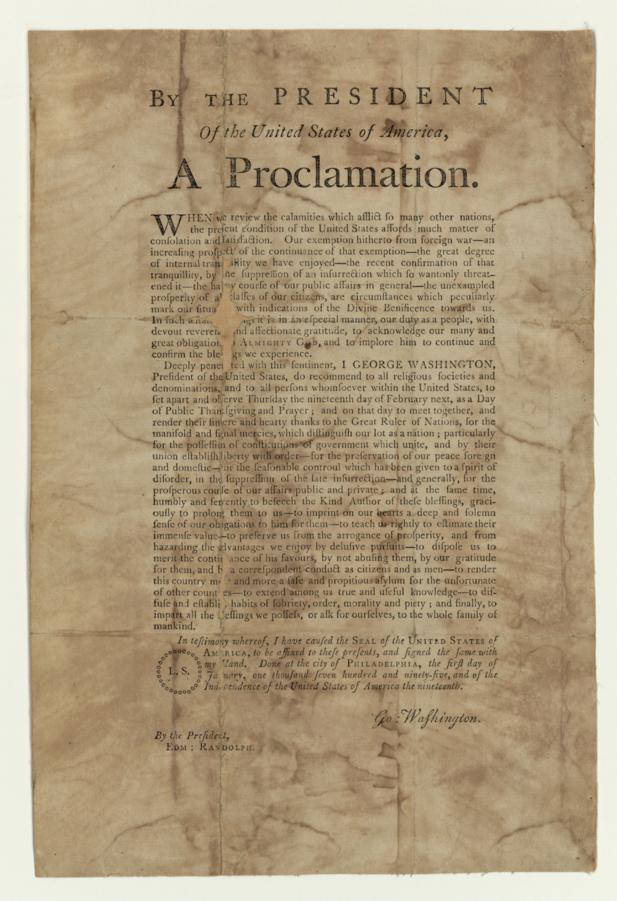

It would be nearly six years before Washington would make another thanksgiving proclamation, but on the first day of January, 1795, the President declared a “Day of Public Thanksgiving” to be observed on February 19th. Again, this announcement was full of implication for ongoing arguments around federalism. Washington called for it after the successful quashing of the Whiskey Rebellion in Western Pennsylvania—a revolt waged over the federal government’s first tax imposed on an American product. Washington referenced these matters in the Proclamation, giving thanks for “the great degree of internal tranquility we have enjoyed, [and] the recent confirmation of that tranquility by the suppression of an insurrection which so wantonly threatened it.” In a strange way, Washington was calling Americans to be thankful for the successful implementation of a federal tax.

Through John Adams’ time in the presidency, the political battles over presidential thanksgiving proclamations between Federalists and Republicans grew. Federalists claimed the religious and civic importance of these national prayer days; Republicans took the mantle from the Anti-Federalists, seeing them as federal overreach and an overstepping of the First Amendment. As historian, John Huston, describes, “During the Adams administration, Republicans organized street demonstrations against presidential fast days, ridiculed them in newspapers and boycotted them.”

The election of Republican Thomas Jefferson in 1800 ratcheted these tensions up to a fever pitch. When the Treaty of Amiens (1802) temporarily concluded hostilities between France and Great Britain, Federalists challenged the president to issue a day of thanksgiving. The Federalist newspaper the Centinel, launched, “that on the receipt of the news of Peace in Europe, the President will issue a Proclamation recommending a General Thanksgiving. The measure, it is hoped, will not be denounced by the democrats as unconstitutional.”

Jefferson responded directly, accusing his Federalist attackers of monarchical tendencies in supporting a step only taken “by the Executive of another nation as the legal head of its church.” In fact, we now know that earlier versions of his famous “Letter to the Danbury Baptists” contained a number of phrases condemning the practice of similar presidential declarations. Furthering his argument regarding the “wall of separation between church and state”, Jefferson made no national thanksgiving proclamations throughout his presidency.

Though James Madison called for a single “Day of Public Thanksgiving for Peace” following the end of the War of 1812, for the better part of half a century following that proclamation, no other American president would call for a national day of thanksgiving until the nation was entrenched in its bloodiest war over issues of federalism, state power, and human rights. In the midst of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln called for national days of thanksgiving and prayer in April 1862 (for “Victories During the War”) and July 1863 (“Day of Thanksgiving, Praise, and Prayer”).

Later that same year, on October 3, 1863 (74 years to the day from Washington’s first proclamation), “in the midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity”, Lincoln proclaimed the national Thanksgiving holiday we celebrate to this day. Every year since, American presidents have issued annual Thanksgiving messages. Lincoln assumes again his role as the nation’s pastor, calling Americans throughout the country and the world to be thankful and repentant. “I do therefore invite my fellow-citizens in every part of the United States (emphasis mine), and also those who are at sea and those sojourning in foreign lands to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a day of thanksgiving and praise.”

In phrasing later heard in his Second Inaugural Address, Lincoln called the nation to pray to a God who was working out both blessings and punishments upon a particular people in mysterious ways. “I recommend to them that while that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings they do also,” he wrote, “with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have come widows, orphans, [and] mourners.”

In many ways, the institution of a national Thanksgiving holiday by Lincoln was his way of finding a genuinely American resolution (a call to prayer and thanksgiving) to a fundamentally American challenge (balancing local, state, and federal authority).

Happy Thanksgiving.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

How Abraham Lincoln created Thanksgiving.

Thanksgiving remains one of our few unifying traditions.

We should be thankful for the sheer wonder of being.

Allen Guelzo, Richard Brookhiser, Joseph Bottum, and Justin Dyer on the thought and action of Lincoln's Thanksgiving and his wrestling with God.

We must not ignore our extraordinary blessings.