Thanksgiving Wasn't Always a Source of National Unity.

Pass the Gravy, Mr. Tucker

The battle for Thanksgiving.

Faced with the gridlock of our day, it is astounding to look back at the accomplishments of the First Congress of the United States. America’s first Representatives and Senators worked from the minute they first met on March 4, 1789, a productive burst that would lay the groundwork for the nascent government. By the time the first session was gaveled out on September 29th, Congress had established the Departments of State, War and Treasury, created the federal judiciary, and approved twelve amendments to the Constitution, ten of which would be ratified as the Bill of Rights.

But lawmaking is the same from age to age, and despite its herculean tasks, the First Congress was marred by partisan contests and petty infighting. Of the sixty-five members of the House of Representatives, fourteen were Antifederalists, serving under the auspices of the Constitution that, just months earlier, they had tried to defeat. This small, vocal minority clashed with the Federalist majority on issues ranging from the momentous—Alexander Hamilton’s financial plan—to the seemingly trivial.

To this day, one incident stands out: the Antifederalist opposition to a national day of Thanksgiving. Though it only takes up half a page in the congressional record, the debate surrounding the “first” Thanksgiving was fierce, and offers a glimpse into the fractious early days of the Republic.

On September 25, 1789, after voting on an appropriations bill, Elias Boudinot of New Jersey rose to address his colleagues. With just four days left in the session, Boudinot proposed that a joint committee of the House and Senate ask President George Washington to declare “a day of public thanksgiving and prayer, to be observed by acknowledging, with grateful hearts, the many signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a Constitution of government for their safety and happiness.”

Still licking their wounds from the previous day (where they had come down on the losing side of a vote to approve the text of what would become the First and Sixth Amendments) two Antifederalist Congressmen, both of the South Carolina delegation, stood to oppose Boudinot’s resolution.

First was Aedanus Burke, who “did not like this mimicking of European customs,” where “two parties at war frequently [sang] Te Deum for the same event, though to one it was a victory, and to the other a defeat.” Next, Thomas Tucker reminded his colleagues that the people “may not be inclined to return thanks for a Constitution until they have experienced that it promotes their safety and happiness (emphasis added).”

Tucker went on to assert that declaring a national day of thanksgiving was a religious matter, and “a business with which Congress have nothing to do.” If, he argued, “a day of thanksgiving must take place, let it be done by the authority of the several States.”

As far as the record indicates, the Federalists’ response was tame by comparison. Boudinot quoted congressional precedent, while Roger Sherman of Connecticut turned to Scripture to defend the resolution. The Great Compromiser cited the “solemn thanksgivings and rejoicings” which took place after the building of Solomon’s Temple as an example “worthyof Christian imitation on the present occasion.” We can only imagine the Antifederalists’ response to the less-than-subtle equation of the Constitution itself with Solomon’s Temple.

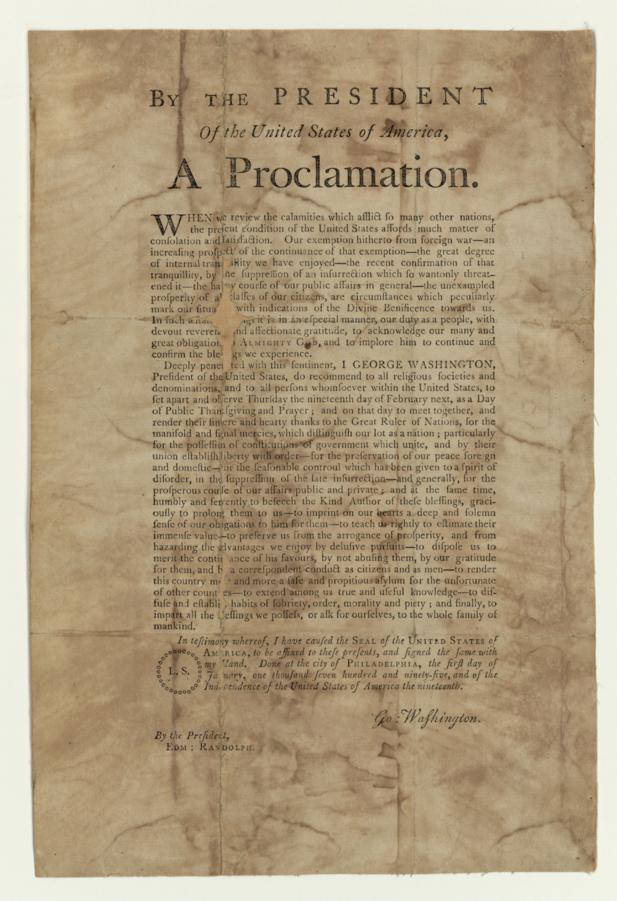

The record is silent after that, save for a note that the resolution “was carried in the affirmative,” and that “Messrs. Boudinot, Sherman” and Peter Silvester of New York were appointed to the committee formed to petition President Washington to pronounce a day of Thanksgiving—which he did, on October 3rd, 1789. President Washington declared that Thursday, November 26th 1789 would be named a “day of public thanksgiving…that we may then all unite in rendering unto him our sincere and humble thanks for his kind care and protection.”

Included among the manifold blessings Washington lists as worthy of thanksgiving was “the peaceable and rational manner, in which we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness, and particularly the national one now lately instituted.”

We can learn a lot from this fascinating footnote to the founding era; we certainly gain some insight into the Antifederalists. Why would Burke and Tucker oppose a national Day of Thanksgiving on the grounds of preserving religious liberty, just a day after they voted against the First Amendment? Think through that question, and you’re well on your way to understanding the “men of little faith.”

But beyond that, this debate reveals something about the character of American politics. This is the moment when factions turned into parties, and the tone should be enough to dispel any notion that “partisanship” is a relatively new phenomenon. In fact, Burke’s comments seem to explicitly link partisan fighting with the American identity. Europeans may feign unity to give thanks in the middle of a conflict, but Americans will keep fighting for what they believe in.

Most importantly, this debate sheds light on what the founders envisioned when they proposed the holiday we celebrate each November. Thanksgiving was originally intended as a day to thank God for the Constitution—it was explicitly religious and political, and the religious and political were linked, in a way that’s hard for us to fathom. Washington’s proclamation makes clear the Federalists’ view that not only the Constitution, but the “peaceable and rational manner” in which it was devised, were part of God’s providence, and worthy of “public thanksgiving and prayer.”

Thanksgiving has come a long way since 1789, and while in many ways that’s a good thing—football and the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade may be on par with the Constitution—we would do well to recover a bit of the original intent behind Thanksgiving in our own time.

As we sit down to carve the turkey this Thursday, let’s all take a moment to give thanks for our country, and for our Constitution. Let’s give thanks for the general welfare it promotes, the blessings of liberty it secures, and most importantly, let’s give thanks just to stick it to Mr. Tucker of South Carolina, one last time.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

How Abraham Lincoln created Thanksgiving.

Thanksgiving remains one of our few unifying traditions.

We should be thankful for the sheer wonder of being.

The Genuinely American Debate over Federalism and Thanksgiving.

Allen Guelzo, Richard Brookhiser, Joseph Bottum, and Justin Dyer on the thought and action of Lincoln's Thanksgiving and his wrestling with God.