Thanksgiving Wasn't Always a Source of National Unity.

Lincoln’s Thanksgiving, And Ours

How Abraham Lincoln created Thanksgiving.

The first Thanksgiving, as we know it, was not proclaimed by the Pilgrims. Not that the survivors of the Mayflower and the first cruel New England winters didn’t give thanks on some autumnal occasions. But the first Thanksgiving, as we know Thanksgiving, was really the creation of Abraham Lincoln. And though Lincoln was descended from the first generation of New Englanders, the back-story of how Thanksgiving became a national holiday has a wider scope than simple genealogy—or even the simple giving of thanks.

November thanksgivings, as local holidays, had been in place for decades before Abraham Lincoln was elected as the sixteenth president in November 1860. He did little more than recognize this when he issued his first thanksgiving proclamation on November 27, 1861, announcing that since the “municipal authorities of Washington and Georgetown” had appointed the following day “as a day of thanksgiving,” federal offices would also shut down “in order that the officers of the government may partake in the ceremonies.” Lincoln himself stayed home, inviting his longtime friend, Joshua F. Speed, and his wife, to a thanksgiving dinner at the White House.

But Lincoln soon took a more vigorous grasp on thanksgiving proclamations. On April 10, 1862, three days after the battle of Shiloh, he issued a proclamation recognizing the “signal victories” the Union armies and navy had enjoyed, and urging Americans “at their next weekly assemblages in their accustomed places of worship” to “render thanks to our Heavenly Father for these inestimable blessings.” He followed this in the summer of 1863, after the twin victories of Vicksburg and Gettysburg, with an even lengthier proclamation, selecting August 6 “to be observed as a day for National Thanksgiving, Praise and Prayer.”

Neither of these proclamations made mention of feasting or harvests, much less turkey. But three months later, on October 3, 1863, Lincoln issued his longest thanksgiving proclamation yet, designating “the last Thursday of November next” as “a day of Thanksgiving and Praise,” not only for Union victories, but for “the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies.” He had been prompted by the suggestion of Sarah Josepha Hale, the editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book magazine, to “have the day of our annual Thanksgiving made a National and fixed Union festival.” And although the actual proclamation made no reference to fixing a permanent thanksgiving holiday, Lincoln (once again at the prompting of Sarah Josepha Hale) repeated his designation of “the last Thursday in November” in a proclamation a year later, on October 10, 1864. (He had, in the meanwhile, issued thanksgiving proclamations in May and September, “to claim our especial gratitude to God” for Union victories.)

Lincoln did not live to issue a thanksgiving proclamation for November 1865, but the practice had already hardened into a pattern. Andrew Johnson issued a thanksgiving proclamation in October 1865, and although he designated the first Thursday in December for the holiday, his next thanksgiving proclamation in 1866 returned it to the last Thursday in November, and likewise in 1867 and 1868. Ulysses Grant did likewise, and so it has been, with only minor interruptions, ever since.

The oddity of Lincoln’s thanksgiving proclamations in 1863 and 1864 is that Lincoln himself did not, in all likelihood, write them. When Sarah Josepha Hale wanted to ensure that a thanksgiving proclamation would be issued in 1864, she wrote, not to Lincoln, but to Secretary of State William Henry Seward, so that Seward could be reminded to prod Lincoln into issuing the proclamation. That, taken together with the style and vocabulary of the proclamations, suggests that Seward, rather than Lincoln, had the largest hand in composing them. (Nor would this be surprising, since Lincoln frequently asked Seward for commentary on documents he had written, and Seward’s signature accompanies Lincoln’s on the thanksgiving proclamations as Secretary of State). But there are also turns of phrase—“the great trial of civil war”…“it has seemed to me fit and proper”…“the axe has enlarged the border of our settlements”—which are peculiarly Lincolnian. And even if the 1863 and 1864 proclamations are a blended effort by Lincoln and Seward, it is still Lincoln’s signature which gave them force. In the end, the proclamations that made our modern Thanksgiving are Abraham Lincoln’s, after all.

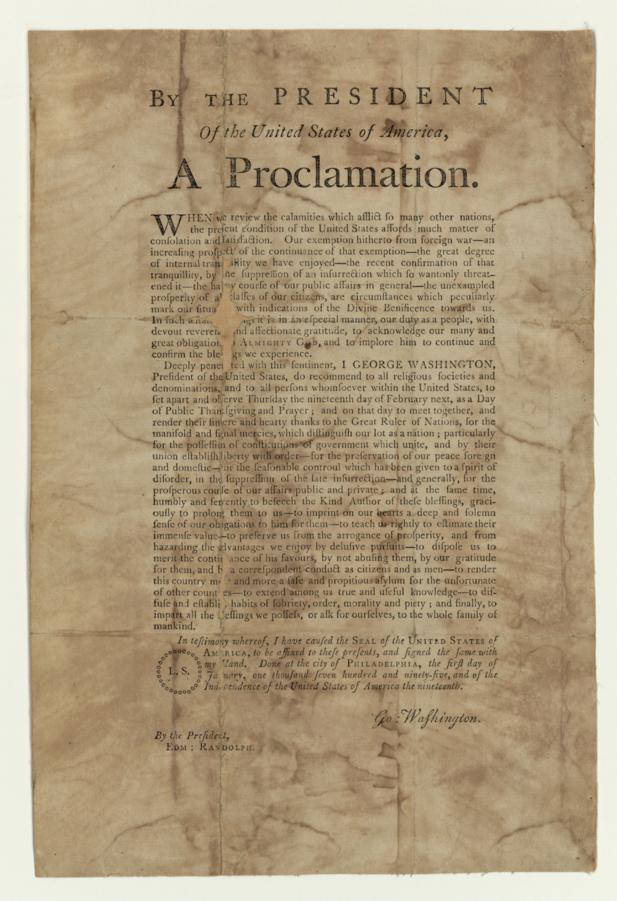

What’s even odder is the very fact of their existence. George Washington tried to set a presidential pattern by issuing a proclamation of thanksgiving in 1789. But Thomas Jefferson, determined to harden the separation of church and state into absolutism, refused to issue any, and Democratic presidents largely followed his pattern until 1860. Neither of Lincoln’s immediate Democratic predecessors, Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan, issued thanksgiving proclamations. For Lincoln, as “an old Henry Clay Whig” and the first Republican president, alliances with evangelical Protestants were much more important and much more routine, and so Lincoln, even though he had only the most modest personal religious profile, tossed Democratic hesitance to the winds and issued repeated thanksgiving proclamations, culminating in the holiday we now celebrate.

Thanksgiving is not supposed to be a political holiday, and there is nothing in Lincoln’s proclamations which invokes political partisanship. But the simple act of issuing them was highly political, and in the historical shadow those proclamations cast, Lincoln’s thanksgiving is yet a reminder of how tenaciously we remain one nation, under God.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Thanksgiving remains one of our few unifying traditions.

We should be thankful for the sheer wonder of being.

The Genuinely American Debate over Federalism and Thanksgiving.

Allen Guelzo, Richard Brookhiser, Joseph Bottum, and Justin Dyer on the thought and action of Lincoln's Thanksgiving and his wrestling with God.

We must not ignore our extraordinary blessings.