Thanksgiving Wasn't Always a Source of National Unity.

God and Mr. Lincoln

Tracing the divine line between thanks and charity.

You’ve heard the line, from time to time: Abraham Lincoln was our great national theologian, and the Second Inaugural Address remains our great national sermon. It’s become commonplace—a hoary platitude of hackneyed American history. It’s a truism that needs little knowledge or thought for its pious intoning.

It’s also absurd on its face. Lincoln was scholastically untrained and, for a theological sophisticate, woefully under-read. He was not much of a church-goer, and he may not even have been a believer, as nineteenth-century American denominational Christians typically phrased belief. He lacked biblical or scholarly languages, and as a busy lawyer and politician, he had little time to contemplate even what American and British theologians were writing in English. He had read the Bible with care, but an anti-religious historian could make the case that what Lincoln took from that reading was the rhetoric and cadences of the King James Version, not the content of its pages.

In other words, we can read through Lincoln’s papers and fail to discern a theology—until, that is, we reach the Second Inaugural:

“Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether’?”

And thereupon every attempt to deny Lincoln as our national theologian breaks down, falls to pieces, and begins to feel a petty and shabby refusal to admit the truth. Sometimes the hoary and hackneyed platitudes are actually correct. Lincoln was the president who understood, more than any other, what it would mean to exist in a God-haunted world.

America has seen its share of great preachers, from the tours of George Whitefield in the 1700s to the public sermons of Martin Luther King Jr. and Billy Graham. The high theological tradition has been weaker than one might expect for an avowedly religious nation, but America has offered up Jonathan Edwards, Horace Bushnell, J. Gresham Machen, and Stanley Hauerwas. Our public theology cannot be called too weak when it includes the likes of Reinhold Niebuhr.

But Lincoln stands alone. Only Jonathan Edwards holds a more foundational place in the national religious mythos, and Edwards was a public figure in the Great Awakening only reluctantly. (His grandson, Aaron Burr, would prove less shy.) And once we see the undisguised theology of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural, we have the lens necessary for discerning that his theological mind was at work long before March, 1864. It’s there in his sense of history in the 1863 Gettysburg Address. It’s there in the metaphors of his 1858 House Divided Speech. It’s there even in his profound understanding of the people’s forgetfulness and time’s silent artillery in the 1838 Lyceum Address.

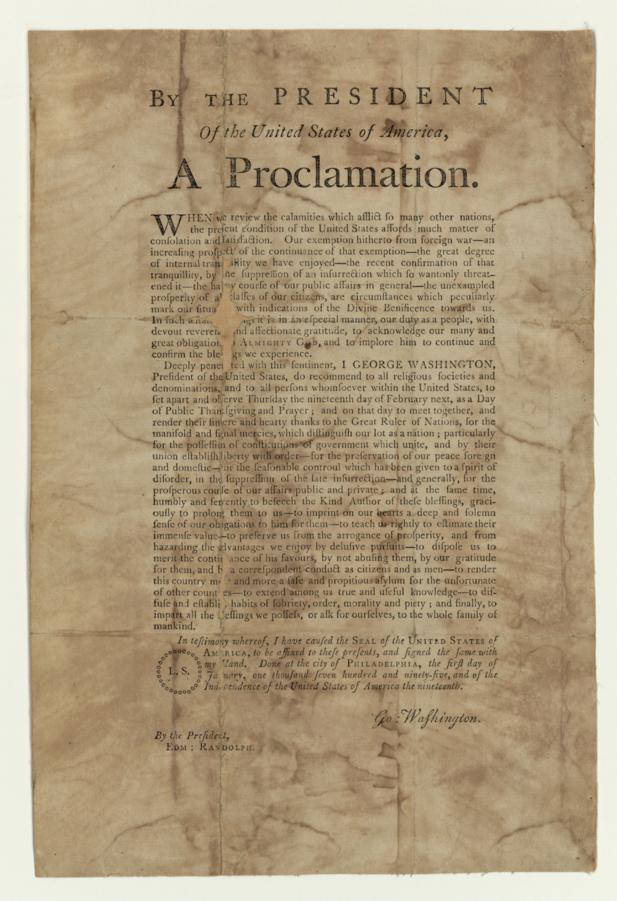

It’s there, for that matter in the 1863 presidential declaration of a national day of Thanksgiving, through which the modern holiday was defined. Written for Lincoln by William H. Seward, the Secretary of State, the proclamation does not rise to the rhetoric of the earlier occasional proclamations in Washington and Madison’s presidencies. But it was Lincoln who ordered the holiday’s creation, responding to letters from Sarah Josepha Hale, the editor of a popular women’s magazine—letters his predecessors had ignored.

And what was Lincoln’s theological imagination? In the Second Inaugural, he expresses a profound thought about how providence could have allowed slavery to come into existence and then initiate its abolition. The Civil War’s slaughter was punishment for both sides for their part in that story.

What Lincoln saw was the humility necessary to live in a world with God. The war proved not a triumphant march to glorious and bloodless victory but proof that Americans were that most theologically-fraught of beings: an almost-chosen people. God’s power belongs solely to God, and we must be tentative and aware of our own sins, even while pressing determinedly toward victory. Only thus can Lincoln ask from us his great peroration: malice toward none, charity toward all.

Lincoln chose his words carefully and theologically. In First Corinthians 5:8, Paul speaks of the “leaven of malice,” and “leaven” here is a perfect word for what malice does, in Lincoln’s sense of the word: it inflates disagreement and bloats every judgment. For this Thanksgiving, like the one in 1863, there remains the deep meaning worth remembering when we contemplate our political opponents: not malice, but charity.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

How Abraham Lincoln created Thanksgiving.

Thanksgiving remains one of our few unifying traditions.

We should be thankful for the sheer wonder of being.

The Genuinely American Debate over Federalism and Thanksgiving.

Allen Guelzo, Richard Brookhiser, Joseph Bottum, and Justin Dyer on the thought and action of Lincoln's Thanksgiving and his wrestling with God.