No War, No Nationalism?

Daniel McCarthy’s First Things essay on “A New Conservative Agenda” is a crucial reminder that the America we know is no longer the founders’ republic, the Cold War superpower, or even the liberal hegemon of the 1990s. The first step toward a governing conservatism is to come to terms with “the century in which we actually live rather than the one shaped by our political heroes.” In this sense, McCarthy offers a realistic alternative both to populist nostalgia for the midcentury consensus, and to elite nostalgia for the enthusiastic globalization and cultural liberalism of the Clinton era.

But I fear that McCarthy is not realistic enough about the challenges facing nationalism. It has never been easy to accommodate the diversity of opinions and interests inherent to a free society on a continental scale. In a country of nearly 350 million inhabitants, it is nearly impossible to take “account of the different needs of different walks of life and regions of the country, serving the whole by serving its parts and drawing them together.” No matter what policies we adopt, there are inevitably going to be losers as well as winners.

The current regime also has winners and losers, of course. Coastal cities, the highly educated, single people, and the service and non-profit sectors of the economy have done well over the last quarter century. The hinterlands, those without college degrees, families, and manufacturing have suffered by comparison. There are good reasons to try to rebalance the ledger in their favor. The concrete proposals in this essay—reorientation of the immigration system toward the naturalization of high-skill immigrants and trade deals that promote domestic employment—might help to accomplish that.

But this sort of prudential rebalancing falls short of the structural renovation that McCarthy recommends elsewhere in the essay. Better trade strategy won’t stop technological developments that have made medium-skill labor less valuable. And immigration reform would need to be much more restrictive than McCarthy seems to envision if it is to seriously alter the size and composition of the labor force. McCarthy rejects what he memorably describes as “palliative liberalism”—efforts to make things a bit easier on Hillary Clinton’s “deplorables” or Mitt Romney’s unproductive 47 percent by means of wage subsidies, tax credits, and other small-bore measures. I am not certain the proposals here—or related suggestions by writers like Frank Buckley or Oren Cass—amount to more than palliative nationalism.

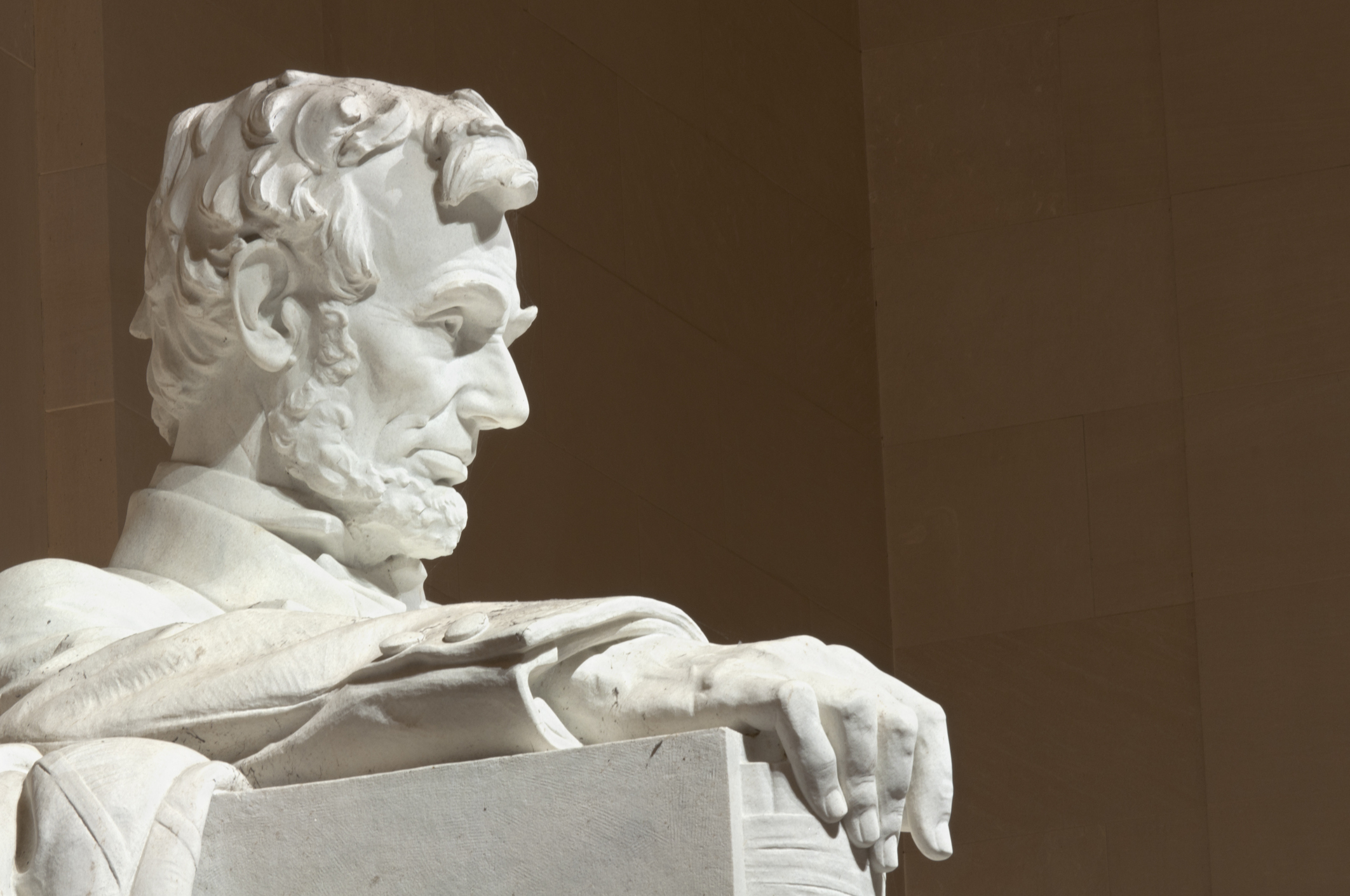

What would be required to bring about a “class compact” comparable to the Jeffersonian ideal of a yeoman society, Lincoln’s vision of a free labor economy, or the midcenturyAmerican dream? The historical pattern suggests that the answer is at once simple and forbidding: major war.

The wide dispersal of property in the early republic was largely a consequence of independence from Britain, which lifted limits on western settlement, and the natural rights ideology that helped to justify it. The industrial economy of the late 19th century was created by the demands of wartime production and protected by tariff and currency policies made politically feasible by the prostration of the South. In addition to the bankrupting of America’s rentier class by the Depression, which neutralized a potent source of opposition to the New Deal, the middle-class comfort of the 20th century relied on an explosion of government spending intended to best first the Nazis and Japanese and later the Communists.

War, in short, seems to be a necessary condition of meaningful national consolidation. It promotes solidarity among the population, legitimizes interventions in economic and social life that would other be unfeasible, and reminds elites that they rely on lower orders for purposes beyond domestic service. That is why campaigns to really transform the structure of our political economy tend to adopt martial rhetoric. The habit is especially noticeable among progressives, whose distaste for war itself does not stop them from declaring war on poverty or calling for a domestic Marshall Plan or a “Green New Deal.”

McCarthy is right to criticize conservatives and Republicans for ignoring or dismissing the real suffering caused by the economic transformations of the last half century. A movement and party that are not interested in making life better for their supporters—to say nothing of their opponents—do not deserve to survive. But over-promising about what can realistically be accomplished is no virtue either. In the absence of another existential conflict—with all the danger and sacrifice that involves—I do not think the prospects for a new nationalism are bright.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Senator Marco Rubio speaks at National Defense University on the need for a ‘pro-American industrial policy’ to counter China.

Following Trump's lead—and Lincoln's.

A conservative revolution is in order.

Our K–12 students need guidance out of ignorance.