Leviathan is hazardous to our health.

Reclaiming Our Republic

A conservative revolution is in order.

WE are no longer a republic of self-governing peoples. The historical and causal questions as to how and when this happened are important but must, at this point, be subordinated to the only meaningful conservative response: revolution. The broad outline for such a revolution is the subject of this essay.

But first, let me clarify why revolution is properly conservative and then supply reasons why, at this time, it is the only proper response left. In our book, Coming Home: Reclaiming America’s Conservative Soul, Bruce Frohnen and I offer a history of Anglo-American concepts of revolution as conservative. This is the heart of that argument:

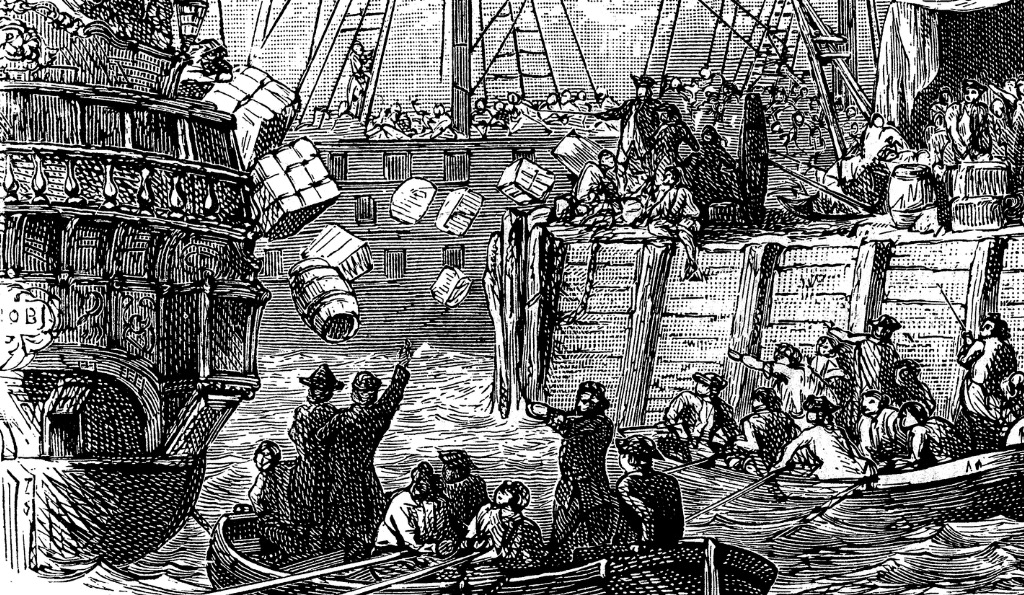

The word “revolution,” derived from the Latin revolvere, meaning to turn or roll back, entered European discourse as an astronomic term concerning the natural course of planets orbiting the sun; when it was applied to political life in reference to England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688, it conveyed the idea of reclaiming. Understood this way, English tradition was marked by a series of restatements of traditional rights, along with institutional reforms intended to better preserve these rights. Whether in Magna Carta from 1215, the Petition of Right from 1628, or the Declaration of Right from 1689, English constitutional declarations forged a tradition played out in the American Declaration of Independence. The bulk of all these documents is taken up with a list of charges against an overreaching king whose innovations threatened inherited rights and liberties. The rebellious English barons, Parliament, and the American Continental Congress all refined and affirmed what was already theirs – they “rolled back” to preserve but also to solidify their inheritance. Changes in the powers of the king and even secession from the British Empire were seen as necessary for the conservation of ordered liberty.

The American Revolution was, more than anything else, a revolution of self-governing people who rejected innovations that threatened their inherited liberties. In response, they were forced by circumstances to craft a new republic and to provide an innovative structure to preserve and enhance their inheritance. Decades of structural changes and more recent assaults on our most cherished values and beliefs have altered the nature of our political, social and cultural order. These attacks now require a response that return (“roll back”) us to the defining principles of our republic, founded on the only proper authority for the exercise of governmental powers—the sovereign will of the people. Crucially, the goal of conservative revolution is to reclaim what is ours by tradition, authority, and right—not revolution for the purpose of transformation or destroying in order to create afresh.

A Republic in Practice

By republic I mean a regime constructed in fidelity to four principles: popular sovereignty; limited government; balanced government; and democratic participation. These were a part of the American constitutional regime from the beginning and remain, theoretically, essential to our self-identity as a “democratic” people. But in our time, each of these has been largely undermined. Our revolution, therefore, must concentrate on reclaiming these four principles as the necessary condition for a free and self-reliant people to practice the art of self-rule. Because these four principles of republicanism have been subverted, and because a free people will never tolerate being ruled without their consent, the test we face is both constitutional and existential.

One of the most important questions about the fate of any republican form of government is whether the citizens are, by habit, disposition, and especially virtue, self-governing. No constitutional or governmental structure alone can turn a disordered people into a functioning republic. Politics in one sense is, as we often say, downstream from culture and social custom. A revolution to reclaim our constitution will not to make us a free people—rather, it is the logical and necessary action of a free people.

Today we have genuine (but superficial) reasons to doubt that we possess the national character necessary for this sort of revolution. It is reasonable to wonder if a movement concentrated on constitutional and political structures isn’t just fiddling while the deeply provincial coastlines burn. I reject this characterization of the American people today. Beginning with the Magna Carta, many of the great Anglo-American conservative revolutions took place decades or even generations after the loss that precipitated them. Deep historical currents made Americans both unruly (we refuse to allow others to rule over us unjustly) and well-ordered (we refuse to accept disordered and capricious laws and institutions). Long experience leads us to love our political freedom and we have often had to fight to preserve this freedom. Our love of freedom imbues our cultural and social disposition even today—a disposition that is encoded into our political DNA in countless ways, most barely visible because they seem self-evident. Such cultural habits, dispositions and long-cultivated affection for self-reliance take a long time to murder. They will not necessarily live on forever, but they were not erased in the last few generations.

Because a free people cannot be manufactured by policy or revolution, the objective of a conservative revolution is not primarily cultural or social. Rather, it is to create the social and cultural space—space now occupied by the state and hence dangerous to the underlying cultural order—for self-governing people to develop and pass down crucial habits and dispositions now under assault. The cultural order is more important than politics, but it is the product of organic growth not revolution, which is why any revolution that will work for the goals of a free and self-governing people is a conservative revolution. All other revolutions will produce tyranny.

The Deep State and The Power Elite

The “deep state” is not the deepest cause of our discontent, but the revolution ought to begin by attacking it because it is (1) the most pressing example of how far from the constitutional republic we have strayed and (2) it reveals very important relationships and power structures that would otherwise be either invisible or the stuff of conspiracy theorists. The deep state is not the administrative state, even if the latter is necessary for the former. I refer to the deep state as short-hand to describe a kind of corruption exercised by a largely hidden elite almost completely insulated from the oversight of the sovereign people—an elite that acts in direct violation of the principles of limited and balanced government as well as democratic participation.

As recently as 2016, most of us now confronted with growing evidence of a concerted effort by high placed officials in different parts of the government who engaged in illegal actions to bring down a duly elected president, would not have believed it possible. These activities (and attending cover ups) amount to a conspiracy to use power to subvert the authority of the sovereign people. Any non-partisan examination of this shocking evidence cannot help but frighten citizens of our republic. After decades of disallowing ourselves to consider such possibilities, we have become woke.

But two facts about what we have learned are just as important as our emerging awareness of these extensive crimes by powerful people.

First, the most conspicuous figures in this scandal are not only denying that they did anything wrong, much less illegal: they are doing so in a way that is insulting to the American people. They tell us that they didn’t spy because, well, they don’t spy. They have the audacity to tell us that their spying is not really spying because they are incapable of such things (and how dare we think otherwise). This is now a standard defense among those who are the primary figures in this scandal as well as their congressional and media supporters. What is plainly true, we are told, is simply not true—because they say so.

Second, a large number of Americans, including a great many who are deeply informed and well educated, refuse to believe that the evidence before the public now constitutes anything illegal or immoral. Why? We can attribute some of it to a kind of partisan ideological purity combined with a deep hatred of the President. However concerning we find this kind of blindness to evidence, it is not as troubling as the blindness of those who are of good will and whose political principles are not narrowly ideological, yet still refuse to believe the evidence before the public. Their refusal reveals the most insidious consequences of the deep state.

The Power Elite

Paradoxically, allow me here to suggest that conservative revolutionaries need to consider the trenchant Leftist analysis of American society and politics from the 1950s, C. Wright Mills’ The Power Elite (1956), which reveals significant truths of our time. Read in light of recent events, this book illuminates some characteristics of what we are now broadly calling the deep state that must be understood well before any conservative revolution can take place. Mills claimed that a relatively small and interlocking set of elites controlled the most important decisions that dramatically affected the United States. In particular, these groups control the institutions in politics, economics, and the military.

In each of these areas, much of what had been characterized by overwhelming pluralism and decentralization for centuries had, by the 1950s, been consolidated in such a way that a few key institutions—such as major corporations in the economic sphere—could exercise enormous control over the economy of a sort that was impossible to imagine a century before. Those who controlled this small number of corporate behemoths not only possessed inordinate power—they belonged to interlocking networks and interest groups that produced a consensus based on their common perspective and collective interests. Moreover, the powerful elites in economics were often directly or indirectly connected to elites in the other two areas of military and politics.

The brilliance of Mills’ analysis—at least from the perspective of 2019—is that it does not rest on any design or conspiracy theory. Those who are most powerful are not likely to be self-aware of how the system in which they exercise direct power and indirect influence works, or to think in a grand way of how they might manipulate or use it for their narrow benefit. To them, as successful people in a successful society that is the envy of the world, their exercise of power is organic and self-evident. It is natural. They are where they are, deploying the kind of power and influence that they possess, because it works well. The consensus the system produces cannot help but look self-evident, prudent, mild, and progressive to those at the top. Many do not even see that they are part of a very small minority that exercises more control over the nation than the vast majority of non-elites who constitute the electorate.

The events of the last three years have revealed what many of us thought impossible. We do not just live (as most conservatives have long understood) in a post-constitutional republic connected to the administrative state: the shock of our corrupt and over-ripe system of self-righteous elites at Trump the barbarian exposed the fact that we have long been ruled by protected overlords. Only a barbarian (someone relentlessly hostile to the conventions of the elite) could have provoked such a reaction that, in turn, exposed the extent of the rule of the elites over the rest of us.

We can no longer ignore the system of lies that the well-heeled peddle. We cannot believe (and yet we are told we must) that the elite promoters of the general will of the people expect us to accept this system of lies upon their moral authority alone. We cannot unsee the astonishingly open connections between the most powerful media corporations and the deep state.

The revolution must begin with the deep state because it not only awakens us to the oligarchic nature of our current regime; the paroxysms of the power elite in this system are the necessary and best opportunity to lay bare to the larger public of free citizens that they are living under the tutelage of schoolmasters (to quote the great French thinker, Alexis de Tocqueville). For the harder parts of the revolution to succeed (such as limiting the scope and power of the federal government), a vigorous minority, supported by an understanding majority, must be fully sensitized to the fact that not only does the current system of elite controls favor the self-interest of those who have long been in power, but that this elite has worked for decades to create the images on the cave walls that control how American citizens interpret their experiences, to create the vocabulary that determines how we talk about moral and political matters, and to persuade us not to trust our own experiences and common sense.

The Administrative State

The deep state undermines the four constitutional principles I outlined at the start (popular sovereignty, limited government, balanced government, and democratic participation), but the more foundational challenge to revivifying those principles in our current system requires a sustained conservative revolution in the structure of our federal government. Without our experience of the deep state I doubt that the real revolution would be possible at this time. But the real revolution will be neither as sexy nor as easy as fighting the corruption of the snarky elites in government, media, universities, and corporations.

The administrative state is shorthand for an extensive system of government agencies created by Congress but directed by the president to manage the American economy, society, and even our moral health in support of the “general welfare” of the American people. These expanding administrative agencies force us to confront some basic questions: over what areas of life ought these agencies have jurisdiction; what powers ought they possess in service of their statutory obligations; and what kind of authorizations do they need to have for both their regulatory scope and powers for them to be considered legitimate? These are all questions that return us to our four principles.

Conservatives have long known and documented the assault on our republican principles of government by the expanding federal state but their critiques have, until now, been largely meaningful lamentations rather than serious calls for reform. The best of the recent batch of such reactions suggests part of the problem. Charles Murray’s excellent book By the People: Rebuilding Liberty Without Permission expresses an appropriately conservative reaction to an intolerable state of affairs, but even Murray’s comparatively hopeful declaration reminds us that there is no quick fix, no single answer to this problem. And yet Murray’s detailed analysis exposes that we live under a lawless government—even without the experiences of the deep state, we have ample evidence that we have lost the defining principles of our republic. For Murray reclaiming our republic is, at best, the work of generations.

I have written this essay to argue that the time for this work is now.

Today we have an awakened public, which is the necessary condition for the relentless education campaign, political activism, and new policy options the revolution needs to be effective.

Strategies for various campaigns in this revolution are already well outlined by people like Murray, but the first task during this inflection point is to use current frustration with the corruption and elitism of our time to teach about the four principles of the American republic. We must use this opportunity to reveal how much we have lost over the decades by means of seemingly prudential additions to the administrative system of governance by elites. In some cases, the overturning of our principles happened with barely a public whimper. The task before us is to review and present our principles and our history in a way that produces a bang discernible to a listening public.

Congress Delegates Our Sovereignty

We all recall from our high school civics class that our national constitution was the product of the citizens of thirteen sovereign states who formed a union based on the unusual idea of “dual sovereignty”—the sovereignty of the states and the nation, balanced, checking each other to prevent abuse, and all authorized by the only singular sovereign acknowledged in the Constitution: the “people.” The people at no point give up their sovereignty but they do empower groups or institutions to exercise different powers inherent in sovereignty at the instruction of the people.

Within the new government created by the sovereign are separate but overlapping spheres of authority and action that harness the self-interest of different institutions to provide salutary checks on other parts of the government. Nothing is as dangerous to American ideas of republican rule than unity of the powers inherent in sovereignty being exercised in one institution.

If we are to address the larger concerns of our time, the most important questions are the scope of authority and the specific range of powers granted by the Constitution to the Congress. Article One, Section Eight of the Constitution enumerates specific powers given to Congress and makes the importance of limiting those powers clear. The famous “necessary and proper” clause opens the door for prudential choices about what very specific powers might be appropriate to fulfill the duties implied by the enumerated powers. The debate over what the Constitution allows as necessary and proper provided the first great Constitutional debate that raged for decades.

The changes to our constitutional interpretation and to the Constitution itself based on this debate didn’t materially challenge the four governing principles of the Constitution. Even later, as Progressives introduced relatively significant alterations to the Constitution (authorizing the federal government to collect income taxes, changing the way Senators are elected, prohibiting the national production, sale and transportation of liquors, etc.), they did so through constitutional means and in deference to popular sovereignty, democratic participation, and limited and balanced government. Since that time, however, the most aggressive expansion of both the power and the scope of the U.S. government has taken place outside of this constitutional process and has undermined all four principles.

Take the 1937 Supreme Court decision, Helvering v. Davis. Considering the constitutionality of the Social Security Act, the Court decided for the first time, and without any interpretive history to support its decision, to overturn the almost universally accepted view of one passage from Article One, Section Eight. Rather than focusing on the necessary and proper clause, as had been typical, the court concentrated on this passage: “The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes…to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States.” From Madison on down, the overwhelming consensus (which was even acknowledged by the Court in this decision) about the meaning of the “general welfare” was that Congress’ powers, herein listed, were only justified so long as they served the general welfare of the United States. The “General Welfare” clause limited the action of Congress by way of establishing a criteria for the use of their delegated (from the people) powers.

In Helvering the Court reversed the meaning of the clause and, in the process, undermined the four principles of the American republic. The long story since 1937 of judicial support for expanding powers of the federal government is more or less in straight line of expanding governmental power without express support of the citizens. By declaring that Congress now has constitutional warrant to act in any way that they believe is consistent with the general welfare, the Court has undermined the limits of congressional scope and power, without the consent of the governed.

The Court has long since given incentives to both the congressional and executive branches to govern in more and more areas of our lives without democratic participation and oversight and in ways that tend to undermine the separation of interests of the two branches. A never-before-heard-of-power of government, to offer old-age pensions and other protections from many vicissitudes of life, need now only be justified on the grounds that Congress believes it to be in the general welfare. Congress has authority over almost every institution in the United States and its powers to exercise that authority are regularly delegated to the executive branch and its federal agencies.

The hard work of revolution must be concentrated on Congress’s delegation of the people’s sovereignty, and it must be based on the four principles of the American republic rather than on short-term expediency (sometimes self-governing communities do not choose wisely or as we would wish).

First, the erroneous interpretation of the “general welfare” clause must be subjected to new court challenges. Failure to get redress in the courts will require a constitutional amendment that clarifies and updates the powers of Congress and the limits of those powers.

Second, we must focus on eliminating the specific constitutional interpretations that violate the principles of popular sovereignty and democratic participation in favor of a textually ungrounded interpretation favorable to a privileged elite.

Third, conservatives must frame a usable interpretation of federalism and the checks and balances between the states and the federal government—an interpretation that is rooted in our first principles but appropriate to our current economy and society.

Fourth, the revolution must be prudential and principled (not narrowly self-interested) in overhauling the entire system of regulations and enforcement that has accrued to the various federal agencies that exercise direct power over American citizens based on an indirect authority that the Court vested in Congress.

Policy, Culture, and American Freedom

The daunting task of bringing the entire regulatory apparatus of the American government in line with the four cherished principles of the republic is necessary before any detailed policy changes will liberate a self-governing people to live freely under their own rules. But that doesn’t mean that all manner of policy choices might not help in the larger process of reclaiming our rights as a free, unruly, and ordered people. The options here are almost endless and many of them involve local and state solutions.

The hard center of all such policy reforms ought to be to invest local citizens in decision-making and to restrict where possible and prudential the reach of government into families, associations, and all the living parts of civil associations and neighborhoods. To the degree that citizens act like citizens instead of customers or subjects, and to the degree that they recognize that their lives are connected in webs of associations, needs, and affections with a wide array of people who live around them, the living currents of a self-ruling people are reinforced. The specific habits, skills, temperaments and abilities appropriate to such freedom will become part of the cultural inheritance of each rising generation.

Readers hoping for a call to the barricades had best remember that we are conservative revolutionaries, seeking a civil social order, not Jacobins seeking blood; that we will fight if we must, but we would still have that fight be conducted in legislatures, courts, and civil action rather than in the streets; that we can and must demand protection of our laws, but will not stoop to the level of the radicals who mock the very idea of law among a republican people.

This is not reform (even though reform is a tool) because we cannot tinker with a system that has rejected the foundational principles of our republic. This is a revolution because we can accept no substitute for the full reclamation of our rights and liberties, and we insist without compromise on the rightful authority of the sovereign people to govern themselves. Unlike revolutions in other traditions, we reject transformation just as we seek no power to remake our world according to some abstract vision of justice.

We must demand all necessary and prudential changes in service of securing, deepening, and expanding the freedoms that are both our rightful inheritance and our most precious gift to our descendants.

We must demand what is still rightfully ours.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

An address delivered February 10, 2021.

An excerpt from the 1776 Commission's report.

To fight prejudice, get the bureaucrats out of power.

Our proud nation and history deserve better.

Big Biz, Big Tech, & Higher Ed are not your friends.