Only justice preserves regimes, not history or tradition.

Nationalism and the Moral Imagination

The traditions of American civilization carry intelligible moral ideas.

Yoram Hazony has written a rich essay that should take its place as a sophisticated defense of traditionalist conservatism. We must continue to add a positive account of American tradition to his powerful defense.

Conservative rationalism, he says, has failed because it pays “little attention to ways in which the traditions of nations are formed and what it takes to strengthen them or even to maintain them.” Hazony is also right to condemn the severing of religious traditions and their related virtues from our public life. “The trouble with these Enlightenment rationalist claims,” as he notes, “is that they aren’t actually true.”

Like Russell Kirk, who called conservatism an attitude toward existence rather than an ideology or a political program, Hazony realizes that the assumptions behind Enlightenment rationality make no sense and can be harmful to the body politic. Insofar as conservatives accept this rationality, they will soon cease being conservative in any recognizable sense.

But there is a second part to Hazony’s argument: to assert that tradition, with adjacent concepts like honor and constraint, should replace conservative rationalism. In this, too, he largely succeeds. Here, I want to elaborate on Hazony’s analysis with two considerations.

The first is that his defense of tradition needs to be both larger and smaller. Hazony focuses on the big important traditions: marriage, citizenship, religion, the common law. But like many conservative defenders of tradition, the more granular elements of that tradition are often left unaddressed.

Sociologist Philip Gorski uses the terms canon, pantheon, narrative, and archive to build a framework that can help determine what is in a tradition and how it may be used. Conservatives should adopt such a framework to understand the components of tradition, because our advanced form of liberalism has itself taken on the guise of a tradition. Unless conservatives can provide our own stories and claims of loyalty and honor, we will lose to the tradition of liberation presented by liberalism (though I share Elizabeth Corey’s skepticism in that regard).

Indeed, Hazony focuses on tradition being measured by its worldly success, but that is not always the case: perhaps the longest tradition in terms of emulation and praise in the West is that of martyrdom, and both its foundational importance to Western civilization and its connection to success are more complex than simply serving as an invoked tradition.

In our case, the traditionalist framework will have a national character almost by necessity. Hazony has argued for a renewed nationalism against a vague and sometimes militant universalism that has forgotten the traditions that anchor us to family, locality, and region. But our tradition is larger still. The American case is a tough one: that of a nation with its own traditions, but also nested within, or the culmination of, multiple older traditions expressing a whole civilization. Hazony himself, in his brilliant defense of the common law, implicitly recognizes this: we cannot understand America without England, nor England without Europe, nor Europe without Calvary.

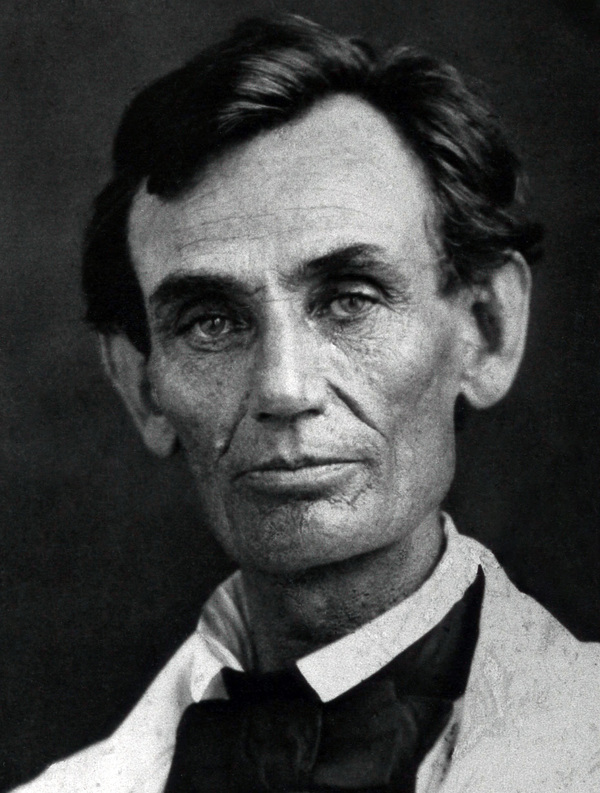

What’s more, Hazony’s insight that Burke was an empiricist not a relativist is crucial. Burke’s first recourse in understanding a political or intellectual problem was to tradition, not abstract reason. We are always, as George Scialabba as written, situated beings. But Burke was not only an empiricist. He did employ a type of “rationality” on the basis of which he was able to distinguish good from bad traditions, and which conservatives today can still draw upon without succumbing to the claim of reaction or nostalgia. That basis is what Kirk (following Burke) called the moral imagination.

In a famous passage in the Reflections on the Revolution in France, Burke refers to the “the superadded ideas, furnished from the wardrobe of a moral imagination, which the heart owns, and the understanding ratifies, as necessary to cover the defects of our naked shivering nature, and to raise it to dignity in our own estimation.”

This moral imagination is not rationalism, but because our moral ideas are ratified by our understanding, they are intelligible, even to those outside the tradition (though they are best understood from within it). Hazony’s references to the Mosaic precepts gets to this point; Kirk himself said that the moral imagination is a power of ethical perception that “informs us of the dignity of human nature.” But further emphasis needs to be placed on the imagination as a conduit and transmitter of tradition.

Hazony has renewed Burkean conservatism with his demolishing of both liberal universalism and conservative rationalism. The way is open to fill in the details and stitch more panels to the canvas Hazony has painted.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Political prudence requires reason—which is why a "conservative rationalism" that embraces universals and particulars alike is needed now more than ever.

The liberal order rests on conservative, not rationalist, foundations.

If local communities are to survive, institutionalized shame toward America must be rooted out.

When a good is not enough, we need to nourish it anyway.

Our new world sheds new light on the relations between reason and tradition.