Only justice preserves regimes, not history or tradition.

Tradition’s Real—and Limited—Value

When a good is not enough, we need to nourish it anyway.

Yoram Hazony’s two-part essay offers both diagnosis and prescription. The diagnosis is that conservative rationalism is but a mirror image of progressive rationalism. Though conservatives prefer medieval Catholic natural law and modern Straussianismto postmodern intersectionality, both of these schools of the Right are similarly built upon unstable, abstract foundations of “reason.” Of course, the natural lawyers and Straussians will dispute this characterization, but nevertheless, Hazony is right to emphasize that rationalism in all its forms tends to neglect the role of tradition in forming good societies. While the conservative rationalist searches for foundations in universal reason, the progressive rationalist rejecting custom and habit is swiftly caught up in universal logics of power, privilege, and oppression.

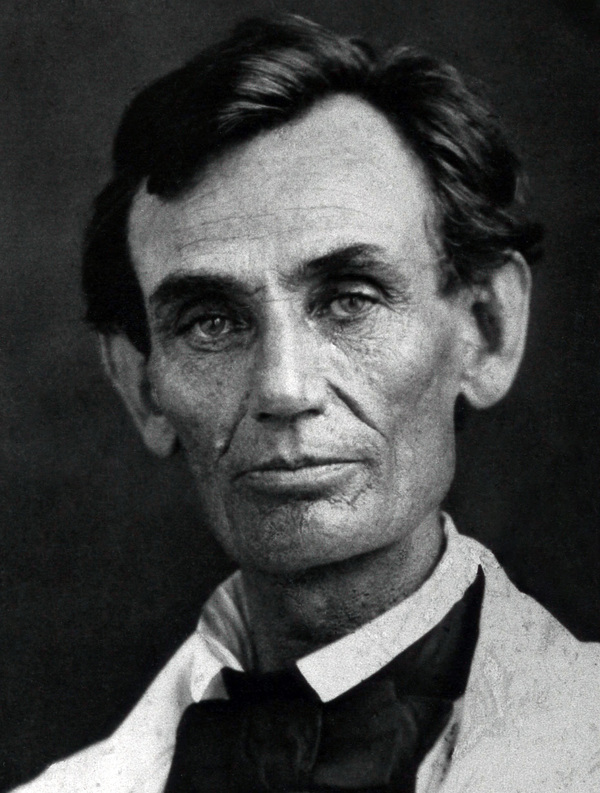

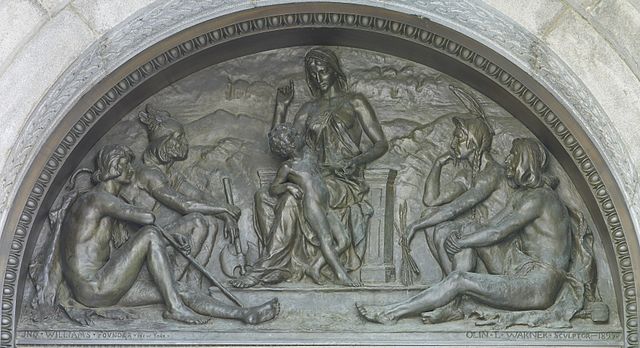

Hazony’s prescription is (in part) to recover the traditions that have formed Western societies over the past several millennia: most importantly the Bible, but also, in the American context, the common-law tradition that informed the thought and governance of the anglophone world. He is right that thinkers like Fortescue, Selden and even Burke are seldom taught in contemporary political philosophy programs. Only the odd “old-school” professor covers them—or Cicero, or Seneca, or the Old and New Testaments, or the sermons preached in America during the Founding period.

The other element of Hazony’s prescription concerns virtue and conduct. He argues that self-constraint and honor must be revived if we are to reclaim our tradition and thrive within it. What are the prospects for this prescription? To be sure, it will be difficult, if not impossible, given the erosion of the past seventy years—from the official devaluing of religion in American schools to the enormously successful sexual revolution.

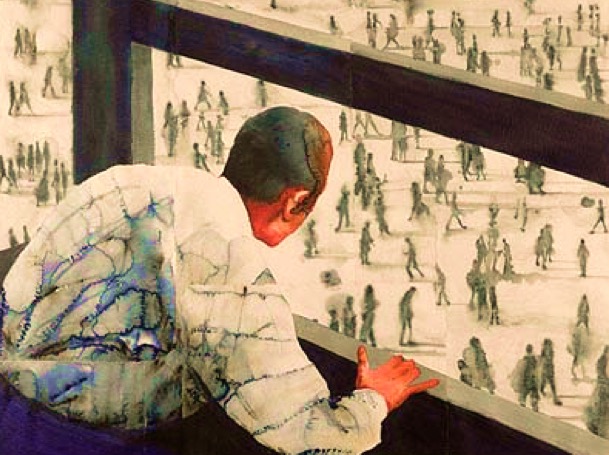

In fact, the difficulties are hard to overstate. Today, as Alexis de Tocqueville foretold, not tradition but equality seems to be the first principle of society in American life—and not merely in citizenship and law. Gender equality, equality of outcome, “marriage equality,” income equality, and further spinoffs goad us on to ever more—frankly, unachievable—dreams. Judgment of any kind is now suspect, for judgment designates some people as worthier of honor and others less so. Some conduct is shameful, other conduct is praiseworthy. Wary of such distinctions, we pretend (to use the awful modern phrase) that “it’s all good.”

Our hatred of judgment has consequences. For instance, it renders the very ideas of self-discipline and constraint absurd. For if life choices are somehow equal, then why should anyone invest thousands of hours to become a great violinist as opposed to a couch potato? More to the point, why should anyone stay faithful to a spouse when no one will judge him for doing otherwise? Musical practice and marital fidelity alike require discipline, discomfort and constraint; they are not as immediately pleasurable as freedom and the easygoing satisfaction of desire after desire.

I think Yoram Hazony’s two-part prescription—recover tradition and revive moral character—is correct on both counts. I am doubtful, however, that it will have the wide impact he and I might desire. For one thing, we are now faced with generations of young and middle-aged elites who have been thoroughly formed by teachers and institutions that have relentlessly critiqued and dismantled tradition. As a colleague remarked to me recently, we really need to get away from the fusty “traditional” ways of doing things in the academy. Her view, that what is traditional is obsolete, is widely shared.

In fact, this points to the very heart of the problem. While Hazony observes that “the conservative focuses on how to preserve the traditional constraints that give his nation its unique form by honoring them to the greatest degree possible,” the enterprise of the American university over the past fifty years has been, in the main, to expose these constraints not as goods but as forms of oppression that must be dismantled, usually in the name of equality.

In other words, tradition is the enemy, not a gift to be cherished. So, while Hazony’s defense of tradition appeals to a certain kind of intellectual and social conservative like me, it will have little traction with many contemporary conservatives, as he well knows, and certainly no impact on progressives. For most so-called conservatives are, in a certain sense, not that different from modern progressives. They embrace one “rationalist” ideology or another, differing merely in the policies and goals to be pursued. And many conservatives are so invested in fighting the culture war right now that they have little time for Cicero, Selden or Burke.

Of course, it is crucial to observe that the reason Hazony’s vision will never become a majority view is precisely that it is not itself a rationalist plan; it is a clear-sighted vision of what we have lost and what must be recovered and maintained, even if only by a few.

To his prescription I would add several other moral virtues: gratitude, humility, deference and respect. These virtues are not widespread in the present day because they are considered passive, weak, and conventional. But they are required for the kind of education Hazony recommends and for a conservative disposition in general. Our primary task in conservative education is not to challenge and upend but first to “listen” to a tradition that we have inherited, on the assumption that it has great value.

We ought also to defend it with vigor and without shame, rejecting once and for all the tired criticism that it is inherently flawed because, as Kenneth Minogue has observed so clearly, “in the crude terms of creative hits, [Western civilization is] the achievement of white males.” Minogue is quite right, and we delude ourselves if we think we can replace it with some kind of sanitized diverse and inclusive reading list. So: let us learn what these men had to say.

Finally, I would add that conservatives ought not think so much in the terms of war and winning. I do not think traditionalist conservatives will win the wider culture war; indeed, I think we have indisputably lost it, at least for the moment. This may at times cause us to despair, as we watch the impact on our children’s lives (and ours) of the degraded culture that surrounds us everywhere.

Rather than despair, however, I think that we should—with modest hope—continue in the work that we know to be good: forming permanent and stable marriages, caring for elderly parents, observing the Sabbath, and teaching those we can about our tradition. We may as well leave the future to God, as C.S. Lewis admonishes us to do, “because he surely will retain it.” Yoram Hazony has charged us with important work in the meantime.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Political prudence requires reason—which is why a "conservative rationalism" that embraces universals and particulars alike is needed now more than ever.

The liberal order rests on conservative, not rationalist, foundations.

The traditions of American civilization carry intelligible moral ideas.

If local communities are to survive, institutionalized shame toward America must be rooted out.

Our new world sheds new light on the relations between reason and tradition.