Discrimination remains a serious problem in American higher education.

Fixing Our Civil Rights Regime

Getting rid of wokeness means finally taking on a third rail of American politics.

What follows is an edited version of remarks prepared for the 2024 Constitution Day Symposium of the National Association of Scholars.

The history of civil rights reform is to a considerable degree a history of constitutional conflict. The civil rights revolution has put substantial pressure on a wide array of constitutional principles—including freedom of speech, freedom of association, due process, and the separation of powers.

At present, we may be witnessing the beginning of a broad course correction. One very important sign is the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, which struck down the diversity justification for affirmative action in higher education. That opinion came as nearly half of the country’s state legislatures pushed back against DEI and wokeness—especially in higher education. These efforts have borne fruit in a way that is resetting the national agenda.

Oddly, we do not discuss these red state initiatives in terms of “civil rights reform,” though that is in fact what they amount to. That we do not articulate these efforts in the most straightforward terms available (preferring to cry “Marxism!” or “postmodernism!”) raises questions about their long-term prospects. Indeed, this failure to name forthrightly what red states are doing seems to suggest a certain amount of uncertainty and anxiety at the center of contemporary anti-woke efforts.

A related problem is that red state efforts against DEI so far have not touched any aspect of federal civil rights law. And that’s a problem because, as we shall see, federal civil rights law is the ultimate source of DEI bureaucracies, DEI training, and other DEI efforts.

If we are to reframe the conversation over DEI and wokeness so that it deals more directly and honestly with civil rights—and civil rights reform—we are going to need to better understand civil rights law.

That might sound to most people like bad news. Who in their right mind wants to pay attention to the twists and turns of anti-discrimination law to understand their country?

My answer is to say, first, if the educated public does not get a better grasp on the basic legal underpinnings of our woke world, efforts to tame it will not be successful in the long run.

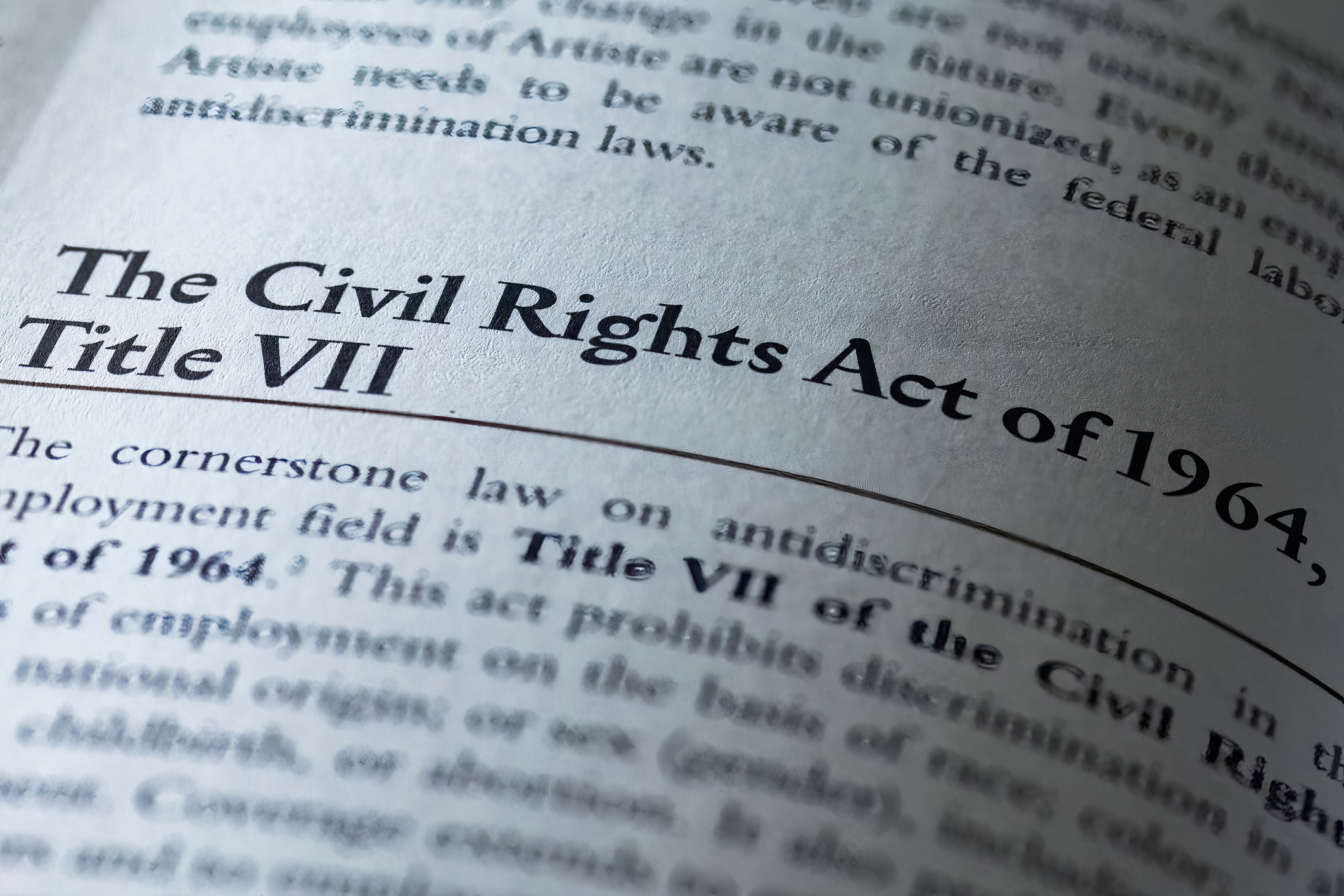

Moreover, civil rights law is not in fact all that hard to understand, so long as one begins in the right place. Just two areas of civil rights law—Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which governs discrimination in employment, and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which regulates sex discrimination in higher education—have done most of the heavy lifting in creating our woke world (with apologies to those who would insist on Title VI). And this can be made simpler still, since Title VII provides the basic terms upon which Title IX is built.

Expanding Title VII

Title VII is at the center of all civil rights law—and the key to understanding it is to track its great expansions over time. Nobody in 1964 would have predicted that the fight against discrimination would become what it has under Title VII.

It is important to note that none of the five most important expansions of Title VII were set forth by Congress in legislative enactments. They were all reinterpretations of the law devised by the civil rights bureaucracy and then consecrated by the federal courts and, ultimately, by the Supreme Court.

The first expansion occurred when the legal definition of discrimination under Title VII was extended beyond what is called “disparate treatment” to include something much broader—that is, “disparate impact.” This distinction may sound annoyingly legalistic, but it’s very important. Disparate treatment refers to obvious intentional acts of employment discrimination in hiring and firing and the like. Disparate impact, on the other hand, focuses on inequalities between groups (for example, in jobs, pay, or educational attainment). Taking these group inequalities as its starting point, disparate impact policy makes the extremely controversial claim that even if no intent to discriminate is involved, any such group inequality is discrimination under the law, an interpretation of Title VII that first appeared in a 1971 Supreme Court decision, Griggs v. Duke Power Company.

The second important expansion of Title VII was to claim that something called harassment is discrimination under the law, which now included the idea of the hostile work environment. This became bedrock law in a 1986 decision, Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson.

The third expansion was to insist that discrimination under Title VII includes making use of stereotypes, which the Supreme Court decided in a 1989 case, Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins.

To belabor what may be obvious, these expansions altered the meaning of what discrimination is—stretching that concept well beyond anything originally intended by the framers of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Our fourth and fifth expansions are usefully treated together. Number four was a significant widening of something very boring: employer liability. Largely because of the new prohibitions on harassment and stereotypes, employers became responsible not only for their own policy decisions (like hiring and firing), but also for any discrimination in the workplace, whether work-related or not.

Understandably, employers sought some way to protect themselves from liability. The answer they received from the EEOC and the federal courts is our fifth expansion: employers must, on their own, take “preventive and corrective measures” to police discrimination in the workplace. Preventive measures include a host of tasks—formulating and publicizing internal company policies, assessing workplace climate, monitoring bias-reporting systems, investigating discrimination and harassment claims, adjudicating appeals, and keeping records. And of course there is the most visible “preventive” measure of all: diversity training.

Title VII’s new corrective measures are at least as important as its preventive ones, extending anti-discrimination law enforcement down to the level of the individual, and with maximum force. As a 1999 EEOC guidance document puts it, workplace correction would include “oral or written warning or reprimand; transfer or reassignment; demotion; reduction of wages; suspension; and discharge.” The Supreme Court gave these last two expansions their blessing in a pair of 1998 cases, which created the Ellerth-Faragher employer liability test. One year later, the high court insisted in Kolstad v. American Dental Association even more clearly that employers must provide what is known today as DEI training.

First Challenge: Group Equality

Understanding how the law has changed over time puts us in a position to begin to reckon with how Title VII, as it has expanded, has been on a collision course with many important aspects of our liberal democratic constitutional order.

The challenge can be summarized under two broad headings. First is the requirement that we must recognize and do something about tangible group inequalities.

One might say that there is a massive legal contradiction here. The Supreme Court, after all, has banned affirmative action as a group inequality remedy under the 14th Amendment—but the problem is that group equality thinking became institutionalized by Title VII’s disparate impact regime. When quotas are not an option (and after the SFFA decision, they seem not to be), the alternative strategy taken by disparate impact policy is to reject any standards that do not produce equal results for groups. These standards—student aptitude tests, grading, and credit and criminal records checks—are the basic building blocks of middle-class life.

The logic of disparate impact law is totally foreign to basic assumptions of our constitutional tradition—but it is alive and well in America today, often advancing under the heading of equity. Disparate impact is indeed the heart and soul of the Biden Administration’s whole-of-government equity agenda, which includes some 300 new initiatives launched since 2022 and the insertion of “Equity Teams” into more than 90 agencies across the federal government.

Second Challenge: Wokeness

Beyond the politics of group equality, there is also a second broad category that stems from Title VII’s expansions. The best term for it today is probably “wokeness,” a useful but also decidedly ambiguous term. A more cumbersome but more accurate label might be civil rights law’s aggressive use of privatized enforcement, punitive correction, and moral and political training. That mouthful is an attempt to capture the combination of pervasive and invasive thought-policing, censorship, and acrimonious penal interpersonal meddling that has become so much a part of democratic life.

However we name it, this second face of civil rights politics is to a significant degree the combined result of the previous expansions of Title VII I’ve sketched out: harassment, stereotypes, expanded liability, and preventive and corrective measures. Taken together, these four legal changes have meant that civil rights enforcement has become almost wholly privatized, turning the public-private divide on its head. Without fully realizing it, we have made a world where fellow citizens, acting in a quasi-public, quasi-private capacity, police one another and mete out punishments that are not inconsequential (above all, the threat of the loss of employment and career).

We need to admit that regulating harassment and stereotypes is unavoidably an effort to regulate society and our social or interpersonal relationships. We need to admit as well that this entails changing the way individuals think about one another—which amounts to a very ambitious program of direct civic and moral education that rides roughshod over constitutional barriers.

If we cannot directly question the law’s prohibitions of stereotypes and hostile workplace harassment, we can at least better define and limit the reach of those concepts and their policing.

Finally, the expansion of Title VII requires a good bit of censorship. Amazingly, the Supreme Court has never addressed the question whether Title VII’s policing of harassment and stereotypes through the privatized enforcement of civil rights law constitutes political censorship under the First Amendment.

All of this taken together is what we mean when we talk about DEI. Title VII training is DEI training. DEI bureaucrats exist mainly because somebody has to do all the work required by Title VII’s preventive and corrective measures. And so long as anti-DEI efforts do not touch the basic architecture of federal employment discrimination law, the prospects for the long-term success of the anti-DEI campaign will remain in doubt.

Civil Rights Civic Education

It is of course true that race discrimination in 1964 was an evil that had to be confronted forcefully. The civil rights revolution was a transformation of immense moral power, and its basic achievements are here to stay.

But that moral reform movement had, to say the least, many unintended consequences, some of them problematic. It is up to us to reconcile this new order with the best features of our constitutional tradition—and that means a broad project of civil rights reform.

Red state labors to date prove that the political energy to undertake that task exists. But if they are to be lasting, those efforts will have to be accompanied by a campaign to help the public understand better how anti-discrimination law is reconfiguring the contours of our social, political, and moral life.

If we are to make progress with this dual task—of civil rights civic education and civil rights reform—it will only be because of an understanding of how anti-discrimination law has expanded well beyond its original meaning and intention.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The administration threatens to use U.S. power globally to advance its progressive agenda.

Talking with liberals can be instructive.

MIT, caught in a bind, reintroduces standardized testing.

The Biden Administration is urging states to impose race-based practices in the schools.

The pursuit of woke social justice is anathema to America’s flourishing.