An analysis of the current American political crisis.

Elite and “Above Reproach”

Self-proclaimed moral superiority is no qualification for public office.

George P. Bush—“P,” not “W,” and not the late “HW,” but one of JEB!’s sons—recently ran for the Republican nomination for Attorney General of Texas. It was to be a promotion for him from his current job as Texas Land Commissioner. Some call him “47” in the hope that 47 will be his Presidential number, as 41 was his grandfather’s, 43 his uncle’s, and zero his father’s.

Alas for P, the voters overwhelmingly denied him the nomination and gave it to the Trump-endorsed incumbent, Ken Paxton, despite various scandals relating to Paxton. As the Gershwin brothers almost put it, they’re writing songs of love, but not for P.

P is young and a Bush, so he’ll probably keep at it. His run gave him the opportunity to think of himself as a revolutionary insurgent in opposition to entrenched incumbency and as a valiant underdog, overcoming obstacles of Bushian prestige, connection, and wealth that would paralyze lesser aspirants. That wouldn’t have been his worst self-flattery, as we’ll see.

Mere Mortals Need Not Apply

Seeking to distinguish himself from Paxton on moral grounds, P said, “if there’s an office that requires someone to be above reproach, it would be this one.” This could be just a normal character attack by one candidate on another, but there may be a bit more to it.

Let’s first consider the statement on its own terms, which suggest that the Texas AG office is uniquely or especially in need of a holder who is above reproach. But presumably even Irreproachable P would concede that, for example, the governor’s character shouldn’t include a tendency to sell pardons for suitcases of cash. Or maybe P thinks “above reproach” means “not susceptible, by reason of family rank, of being criticized.” That isn’t the dictionary definition, but it might well be the Bush definition, given the family’s membership in the American aristocracy and the legendarily difficult relationship between some of the Bushes and the English language.

Even if he meant “above reproach” in its normal sense, P’s statement wasn’t just an attack on Paxton but also, in all likelihood, a not-so-humble brag. This interpretation is supported by another instance of such behavior during the campaign. Here he was in a television interview, saying why the voters should elect him:

Well, I’m a Christian. I’m a father and husband. I’m very plain and simple. What you see is what you get. I commit to the people of Texas these, like I have these past seven years to wake up every morning and fight for your values and the Texas way of life. And whether that’s confronting the national government or local or county governments that are standing up to the will of the legislature as reflected through the people. I’m going to be an attorney that’s above reproach that will take my vows seriously – to my wife, to the Constitution, to the laws of the state, and do so above reproach.

If Paxton is in fact a scoundrel, many voters apparently preferred him to a “very plain and simple” man who says he is, or at least will be, “above reproach.”

Think of the worst boasters and hypocrites you’ve known, outside of politics, and then the best people you’ve known. In either group, has any of them every claimed to be “above reproach”? It just doesn’t come up in normal conversation, and normal people (which excludes most politicians) wouldn’t think to express such thoughts. Normal people are constrained by good taste from doing so, and also by the tactical consideration of avoiding a trap: If modesty is a virtue, wouldn’t P’s kind of self-proclamation logically be an activity reserved from the virtuous, not to them? The virtue-signaler often ends up signaling that squirreliness. As they say in Texas, “Don’t buy no cattle from no knight who brands ’em Property of le chevalier sans peur et sans reproche.” Yet “Well, I’m a Christian and above reproach” is apparently something a GOP politician can say and not be laughed off the stage for saying.

There are many in the GOP who hope for religious probity in their politicians. Many in the group may appreciate P’s statements as his way of assuring Christian voters that he shares their faith and the values associated with it. Their hope is likely more sincere than any particular politician’s probity (as to P’s probity in particular, I have no opinion), but they may think my sanctimony detector is too sensitive. Even if it is, they, as P’s co-religionists, should remember the sturdy doctrine in The New England Primer that “In Adam’s Fall,/we sinnèd all.” This might give him another reason to be less boastful about his virtue—and them less reason to encourage such boasting. The non-believers in the party may be more interested in his secular capabilities, and the coalition between them and the religious right must be maintained if the GOP is to have any real power in this country. “Though P’s devout,/we turn’d him out.”

For any audience, it would seem both desirable and possible for a politician like P, if not P himself, to be defter in his appeal to religion and virtue. For example, Senator Marco Rubio’s current Twitter bio attempts to define him favorably with a string of labels that starts with “Christian.” His bio has the virtue of being brief, and it can scarcely be interpreted as a boast about Rubio’s irreproachability. It’s a mild ingroup signifier carried by short wave radio, as opposed to the tsunami of self-praise with which P gushed about himself.

We conservatives smirk all the time at the virtue-signaling of the wokesters, but we—at least the likes of P—don’t always avoid being smirk-worthy. If P’s appeal to irreproachability were merely a breach of decorum, that would be something that we who have transacted politics, as consumers, in the age of Clinton and Trump could live with. The problem is that P’s appeal goes beyond that and connects with a bigger problem with our elites.

Yet Another Way the Elites Are Better Than We Are

A recent American Mind article took a suitably dim view of our elites in a way that may connect to our encounter here with Irreproachable P. In “What Trump and COVID Revealed,” Glenn Ellmers accurately described the illegitimacy of so many of our elites, as well as the role played by the titular forces in exposing that illegitimacy. The article updated a 2018 American Mind article by John Marini, “After Trump: The-Political-and-Moral-Legitimacy of American Government.”

Ellmers focused on the elites’ pretension to legitimacy from expertise, as well as their pretension to expertise. Ellmers could have continued: These first two pretensions are complemented by a third pretension, the pretension to moral authority. In contrast, one of the things many people liked about Trump was his avoidance of any such pretension, particularly in the moral category: Trump may have been a low-grade scoundrel at times, but he may also have been the only major recent political figure who wasn’t an obvious hypocrite. (Bill Clinton was a special case, because his effective mitigating technique was, with that smile, to let you in on the joke of his hypocrisy.)

Sadly—no, terrifyingly—many of our elites probably aren’t hypocrites about these things. It seems that they really believe they have expertise, legitimacy, and moral superiority. In the case of P, there’s no way to know if he really believes his proclamations of irreproachability. But he probably maintains his self-regard with at least a modicum of sincerity.

Surely it was thus with Caroline Kennedy, who in 2009 had a brief go at succeeding Hillary Clinton as U.S. Senator from New York. In a notorious interview, she managed to fill a few minutes with over 100 instances of “y’know” without explaining why anyone should vote for her. She probably thought it was self-evident that her country would benefit from the “public service” of yet another Kennedy. She withdrew soon thereafter, no doubt disappointed in us, not herself.

If you think I’m picking on the likes of the Bushes and the Kennedys, I plead guilty, but my crime is a misdemeanor to their felony, which is picking themselves, generation after generation, as presumptively worthy of consideration as our leaders. Derision is a mild punishment for them.

Daylight, Magic, and Modesty

One advantage of a hereditary monarchy—especially a traditional inbred one, not one like the Bushes—is that respect for a family “dedicated to public service” only fleetingly survives something like sight of a Habsburg jaw. It has more than once been observed that Bagehot’s injunction, as to his country’s royalty, that “We must not let in daylight upon magic” can’t easily be obeyed in a world of modern mass communication. Maybe so, but it may take modern mass communication to keep the daylight out, as in North Korea to keep the myths of their god-kings in obscured circulation.

If politicians and other members of our elites are superior to us, or think they are, they should keep it as private knowledge, or private belief, uncorrelated to the choice or chance of faith. And they should allow themselves to be tormented by private doubts. Unfortunately, once elected by some margin, slender and perhaps dubious, or otherwise elevated to elite status by undeserved advantage, inexplicable luck, or worse, they come to believe in their status. And then the institutional machinery kicks in to reaffirm their delusions of grandeur or even slight superiority—the marching bands, the security details, honorifics like “Honorable,” and the like.

“We must not let in daylight upon magic” may have made sense for Bagehot’s constitutional monarchy, at least before the appearance of many of the current Windsors, but it should not be applied to our elected leaders. The pomp and other magic encourage them to think of themselves as superior and also may discourage their subjects from thinking of them with the skepticism—the presumption of incompetence and venality—that they deserve. As to those leaders, the better injunction might be that we must not let in magic upon daylight.

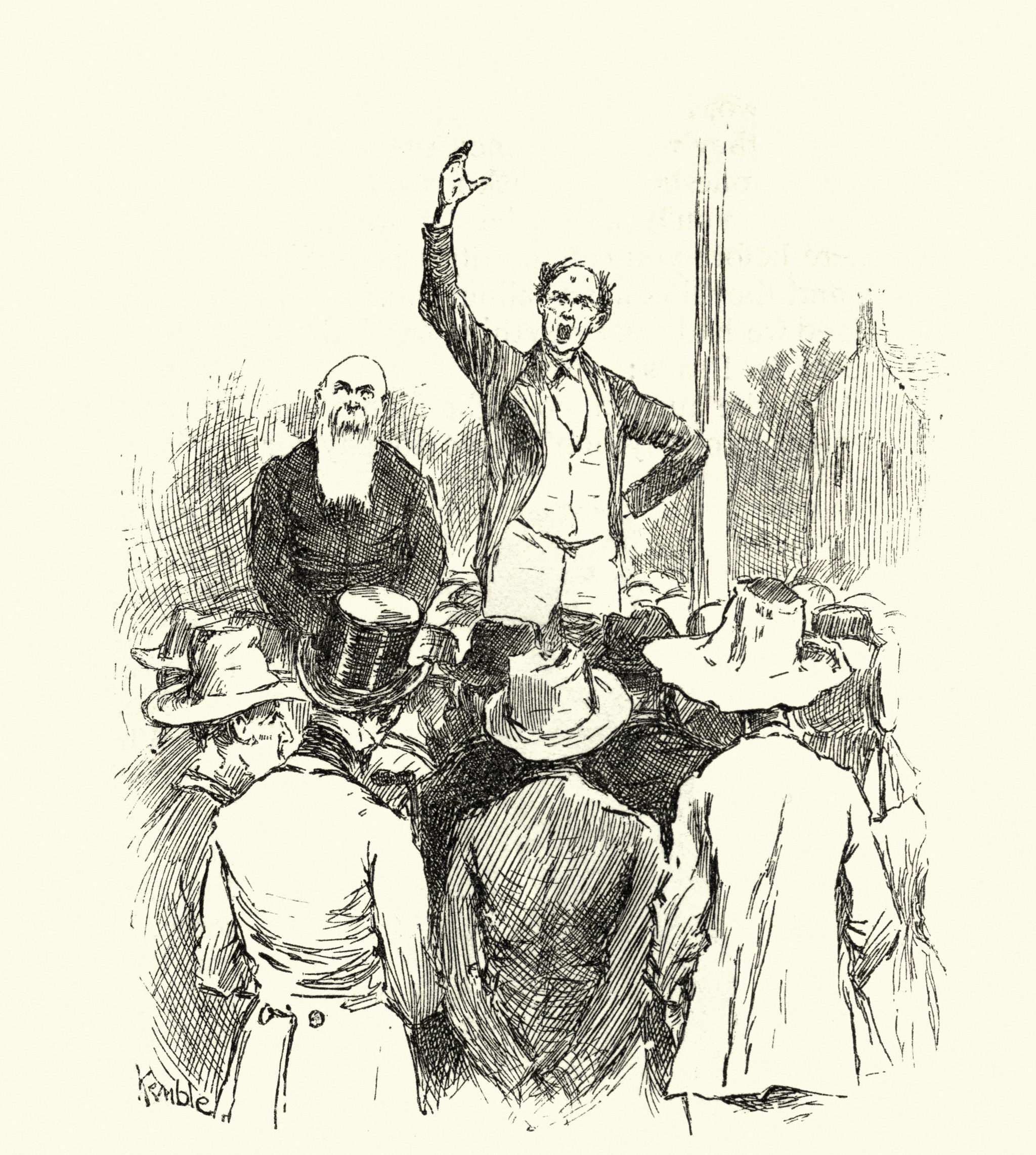

Our own entitled aristocracy is often even more odious when, at rallies and on other occasions, it mixes the magic with a phony exterior of down-home populism: “I will never stop FIGHTING for YOU!,” they roar, before being escorted to the waiting limousine to take them to their private aviation, far from the objects of their condescension.

In this republic, let virtue among the elite be its own reward and its own silent self-proclamation, or at least let the elites’ self-proclamations of virtue be heard, if at all, solely at intimate gatherings like those of the Bush clan. The self-proclamations can be accompanied by the whistle of the salty winds of Kennebunkport and a muted rhythm section of gentle back-slapping. Or maybe, for poor P, it’s just a commiserating hug.

The rest of us would probably prefer to be gathered over drinks with an amusing scoundrel, whether in Texas or at Mar-a-Lago, for an evening above reproach.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Shame at the experience of subjugation can inspire Americans to reclaim their sovereignty.

Things boil down to a question of "Who rules"?

You don’t need an epidemiologist to know which way the wind blows.

The hard facts—and hopeful opportunities—of a post-pandemic world.