The Right should reclaim the populist ground that enabled its biggest victories.

Zombie Outbreak

Upper- and lower-class skeletons are emerging from their respective closets.

The business suit once set the comfortably affluent apart from the proles. Paul Fussell, indispensable analyst of class signals, wrote in his 1984 book Class: “the suit ‘not only flatters the inactive, it deforms the laborious.’ (And the athletic or strenuously muscular: Arnold Schwarzenegger looks especially comic in a suit.) For this reason the suit…was a prime weapon in the nineteenth-century war of the bourgeoisie against the proletariat.”

Today, however, the rich take shirtless selfies; strong bodies are now a signal of the upper classes. Make no mistake, even in Fussell’s era upper classes were skinnier than lower, but not ripped. Musculature signaled too much bodily labor. But now, the “working” class no longer “works” so much as serves—usually on commission at the Boost Wireless store in your local strip mall. Meanwhile the leisure classes do CrossFit, chug whey protein, avoid seed oils, and inevitably fail at cheating death.

Such reversals saturate our new Age of Aquarius. Our ancient antagonists—scarcity, isolation, body odor—have been replaced by their opposites. Everything is mixed up. The class signals are crossed. To analyze them is to illuminate a path through the darkness.

Ends Meet

One such signal is visibility, or the lack thereof, among the very highest and the very lowest classes.

According to Fussell, there are not five classes in America (Upper, Upper Middle, Middle, Lower Middle, Lower), but nine:

Top out-of-sight

Upper

Upper Middle

—

Middle

High proletarian

Mid-proletarian

Low proletarian

—

Destitute

Bottom out-of-sight

Why “out-of-sight”? Since the Depression, Fussell argued, true wealth learned to hide itself out of a combination of shame and security—a totally different outlook from the 1890s, when the very wealthy “exhibited themselves conspicuously.” A merely upper-class person can be identified by a long, winding driveway leading up to a manor. But the truly upper crust—you won’t see them at all. They have “invisible driveways.”

“Now they hide, not merely from envy and revenge, but from exposé journalism…and from an even worse threat…foundation mendicancy, with its hordes of beggars in three-piece suits constantly badgering the well-to-do.”

As for the bottom-dwellers, they are “equally invisible, when not put away in institutions or claustrated in monasteries, lamaseries, or communes, then hiding from creditors, deceived bail-bondsmen, and gulled merchants intent on repossessing cars and furniture.”

Invisibility is not the only thing shared by both the grandest and the most abased among us. Fussell listed others: Reliance on others’ money. Total intolerance of authority. Destinies shaped entirely by their forebears. This shouldn’t surprise those familiar with Horseshoe Theory. The highest and the lowest classes mirror each other.

But if the gruesome extremes of class spectrum were once an invisible minority, their behavior has increasingly imposed from both ends upon the middle classes. It’s becoming increasingly difficult to stuff the mess in the closet. Ugliness bursts out—onto the streets, onto our screens, into our feeds.

Favela-ization

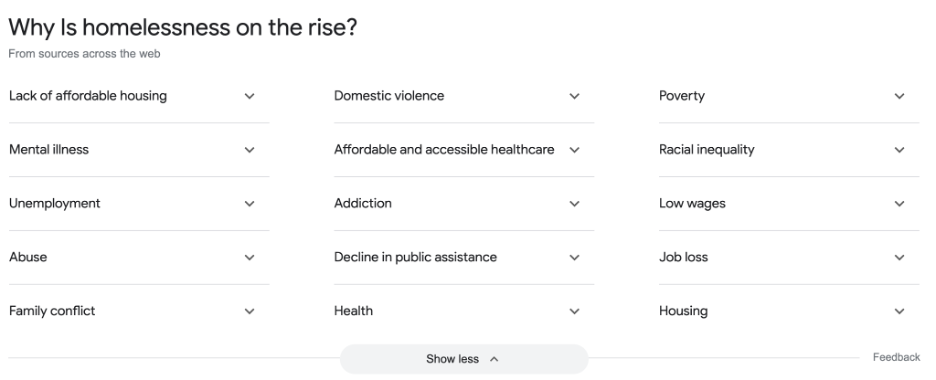

Many reasons are given for the total domination of West Coast cities by “homeless” people. Google leaps to offer reassurances to those asking awkward questions:

These “accepted” explanations emanate from various conglomerations of private and public entities—”The Homeless Industrial Complex”—as propaganda both shielding them from blame and keeping the money flowing. Missing are better explanations: Reagan’s deinstitutionalization, woke Ninth Circuit decisions, the social media panopticon that makes it impossible for virtue-signaling liberals to crack down on vagrancy without copping to it, as they have always done in the past.

But these are all inflammatory factors aggravating the real cause, which is very simple: demographics. Take a look at the most recent videos of homeless encampments in San Francisco and Portland. What do they look exactly like? Why, South American slums. As the middle class evaporates, favelas accrete. The reason why we see more “out-of-sights” is because there’s simply too many of them to hide. Parts of San Francisco look like Third-World slums because that’s exactly what they are.

Walk down to one of the open-air drug zones in San Francisco, as I have, and ask around. The paid “community facilitators” will all tell you the same thing: Honduran drug gangs act as police, real estate brokers, and chambers of commerce all at once.

But the people building California’s favelas aren’t the noble savages we see on T.V. Nor are they even the cooperative vagabonds of Fussell’s time—the type who, in George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, wandered 20 miles every day between public barracks which were intentionally spread out to keep the flow of vagrancy moving. No, these are violent, deranged, hideous, drug-fueled criminals. Walk 20 miles? How about no. How about you walk 20 miles to avoid me?

The reason it seems like there’s so many more homeless people is because there are so many more homeless people. The class itself has grown beyond its ability to hide or be hidden.

The Top of the Hill

As Peter Thiel famously said, the worse things get at the bottom of the hill, the more valuable the houses on the top. We instinctively—but fallaciously—imagine that rising inequality means fewer people in the “1 percent.” But though the erosion of the middle class means the majority get booted downward, a minority get sifted the other direction, up into the elites. And like the destitute, the elite classes have broken containment.

Normal people are appalled at elite behavior. Fussell characterized the uppers as dull and careless, with poor taste—allergic to ideas and even more allergic to talking about them. He cited as an example Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney’s Live a Year with a Millionaire (1981). Vanderbilt made the mistake of becoming visible, showing off his stupidity with a litany of embarrassing banalities: “they are a cosmopolitan group who come from places all over the States,” he wrote, describing the people who attended his parties.

But it’s not in dullness that the true ugliness of the elites lies: it’s in their total abandonment of anything resembling mainstream morality. Marx, in the Communist Manifesto, suggests that the proletariat adopt the elite tendency to share wives as a salvo against their “rules-for-thee-not-me” sexual practices. Indeed, one of my formative memories involves stumbling upon a roll of freshly developed vacation film on a kitchen table of an elite family member, and shuffling through pictures of wholesome togetherness, only to be blindsided by four hairy vaginas, side by side and disembodied from waste down, dancing in the sunlight. The filthiest apartment I’ve ever seen belonged to a trio of ultra-rich Jewish girls at UCLA, its most memorable highlight a greased-up sex swing.

The limitless perversity was revealed most recently by the #MeToo movement. Matt Lauer’s office-door-shutting button, Ed Buck’s “party and play” deadly chemsex routines, the Google cult leader’s 100-man challenge, Balenciaga pedo ads, and of course the Steins, both Wein and Ep. The clearest example possible of elite misbehavior departing the shadows: Washingtonian striver twink captured getting reamed in the Senate’s chambers.

More bizarre, and honestly much more disturbing, are the ultra-elites’ odd but non-sexual behaviors, which seem to betray a power-drunk view of humanity: cats toying with mice. There was the other Washingtonian striver twink twice arrested for stealing womens’ luggage. There’s Marsha Berzon, the Ninth Circuit Judge who stripped every municipality in nine states of their ability to enforce vagrancy laws. There was SBF, promulgating effective altruism while admitting, sloppily via unsecured text message, that it was all an act. And the most bizarre of them all: George Soros, who goes completely 180 against Fussell’s “out of sight” playbook by brashly descending from his ivory tower to mess with the middles and proles on their own turf, speaking proudly about interfering in local elections thousands of miles away from his invisible driveway, for seemingly no reason besides his own amusement. This kind of exhibitionism represents the extreme of elite perversity.

Soros can afford it, because there’s little immune system left—outside the regime-approved sexism and racism accusations that have actual teeth, á la #MeToo—that would enable us to act on our shock when elites show us their a**ses. Soros, just for example, can unapologetically fund activist D.A.s who lead to the actual real, measurable murder of innocents with virtually zero immediate consequences. Had he asked a female employee to sit on his lap, or said one very bad word, he’d be toast.

Even on the “good guys” side, CEOs increasingly want to follow Musk’s model—to be the public star, blemishes and all. They hire agencies like mine to turn them into sassy, relatable Twitter stars. In 2006, the heir of the Johnson & Johnson fortune, Jamie Johnson, released a documentary called The One Percent, fascinating in that it combines absurd Marxist naivety with unbelievable access to powerful people like Milton Friedman and Jamal Khashoggi. Already by 2006, the younger elites were slouching toward the spotlight. One of them, a handsome Italian baron in his 20s, hires a publicist so he can be more than just “another kid with money” in America. He ends up on Zegna ads in Times Square, and in Hollywood pitch meetings for a Kardashian-style reality show—unthinkable to his recent ancestors.

In times past, the restless baron would’ve likely cultivated a different public persona. Polls of Fussell’s day—the 1980s—showed that the vast majority of Americans wanted to be upper-middle-class. The self-help of the era instructed all dreamers, even top executives, to dress in upper-middle-class garb.

The heavy inertia of a large middle class brought everyone else down to its level. The very-rich were dull—their atrophied brains embarrassed them. Today? We worship them—their dullness especially—in large part because the upper-middle-class has shrunken to a sad, unrecognizable prune. Ask Americans which they’d most like to be today, and the honest ones will all say “elite.”

Premonition

The most popular film and T.V. genre of the past decade has been the zombie apocalypse. The Walking Dead, for example, is the most watched cable series of all time. It’s the definitive horror genre of our day. And it’s all about the new visibility of the formerly bottom out-of-sights.

Our obsession with zombies, and our ability to make films about them, should evince societal health. Our collective consciousness can still formulate predictions of future threats, and deliver awareness of those threats to the rest of the corpus. Hence the old premonition films about pandemics, and the new ones, like Leave the World Behind and Civil War, about civil war. Telling that new zombies differ from old zombies in that they don’t rise from the dead. They’re always created by disease, and the disease is caused by some error of the powerful.

If today’s zombie movies signify a collective nightmare about the newfound visibility of the bottom out-of-sights, their counterpart on the top is the almost equally popular (and growing) “pedo elites” genre, which includes True Detective Season 1, Taken, Top of the Lake, and virtually every Scandinavian murder mystery on Netflix. Last year’s surprise Christian hit Sound of Freedom shows us where things are headed.

However, no amount of nervous fantasy stymied our destiny, and now the streets of Los Angeles look not just like a zombie movie, but a particularly disgusting one. Nor should we expect that the pedo elite genre will do anything to protect us from the brazen ugliness of the good and the great. It will continue to seep out of the closet, and to appall us in ways we’d never thought possible in a first world country. As above, so below.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Feminism seeks the extinction of the kind of men who built the world.

Meditating on Italy’s cultural treasures can help stop our civilizational spiral.

The legendary basketball coach represented a vanishing type of American masculinity.

We are rapidly becoming post-civilized.

But humility, courage, and loyalty might.