Bringing what is said in private into the open.

What I Learned at the Bull Auction

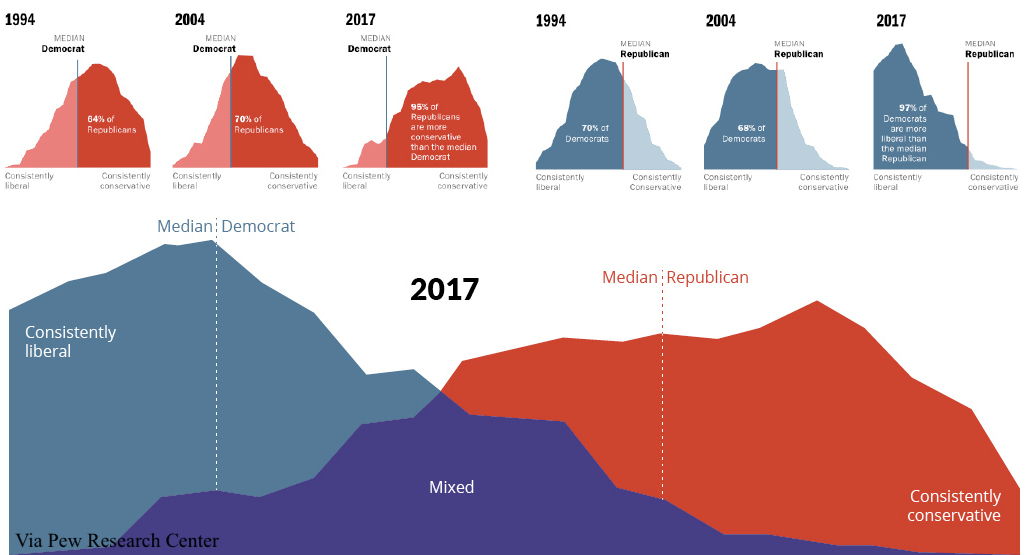

The divisions in our country run along numerous fractures.

“Well, the weather’s a bit nicer than I was expecting,” the auctioneer announced to the crowd in a deep, even twang. It’s below freezing, with occasional light snow. But given that this was late February in Montana, the auctioneer was probably being accurate.

We’re in a pleasantly heated livestock auction barn in a rural location in southwest Montana for the latest edition of a bull sale that has been taking place annually for more than forty years. As best I can tell, of the hundred or so folks there, I am the only interloper.

I’ve been invited by a friend of mine, a fifty plus year Montana rancher who once had one of the largest sheep operations in the area. In his “spare” time, he has been a sometime-academic economist and innovative policy entrepreneur. My host is a true Montana character—he once shot a neighbor’s pig that had repeatedly trespassed onto his land and barbecued it as the main course for his wedding feast two days later. The food here, while presumably not shot for trespass, is prepared and served by the wife of the selling rancher. It’s a true country spread, with plenty to go around, and, unsurprisingly, some wonderful steak.

Other than my friend and I, everyone else is here to buy, save the clutch of kids who, dressed in their finest Western wear, have taken off school—to be here and learn something that will probably be more important to their future lives than geometry class. A teenage girl who in another environment might be posting selfies on Instagram for likes, is sitting with her mother, poring over a carefully marked-up catalogue of bulls for sale. The catalog has a bewildering (to outsiders) array of statistics attached to each animal ranging from scrotal size (really) to predicted marbling or susceptibility to certain diseases.

The auction proceeds at a rapid pace—with the auctioneer praising one particularly fine specimen as “A big-time herd bull with quality to burn”—this sort of flattery goes on with reference any number of bulls that seem similar to my untrained eye. The wealth of numbers would put any corporate spreadsheet jockey to shame, but the ranchers are digesting them all and then making immediate bets in real-time. It’s pretty far removed from the days of just looking and guessing, although a couple of ranchers I talked to did say that visual inspection still makes up half of their decision-making.

Agricultural America

These ranchers are representatives of a romanticized but forgotten America—one that not many people, much less very many of our elites, have contact with. They represent one of Edmund Burke’s “little platoons” that form the basis of any healthy society, though they are hardly living in a past age—I overheard one rancher say he’d gone skiing the previous weekend. And some bids at the auction were taken over the Internet.

Good cheer and neighborliness were on display among the ranchers, many of whom seemed to know each other. Much of their business is done on trust—old-fashioned handshake deals that would be impossible in a big city among strangers. Our founders, most of whom had a background in agriculture, constantly referred to the healthy moral effects of country life. Jefferson called the pursuit of agriculture “the surest road to affluence and the best preservative of morals” and believed that vast agricultural lands were necessary for the best preservation of the Republic, a philosophy he used to justify the Louisiana Purchase over Federalist objections. Benjamin Franklin wrote of wealth gained through agriculture as morally superior to the other two ways of getting rich, namely force or commerce.

The founders’ praise of agriculture was not mere moralizing, but deeply embedded in the practical Lockean theory that so greatly influenced them. Locke himself endorsed the benefits of agriculture extensively in his famous Second Treatise on Civil Government, at one point observing that land “that has no improvement of pasturage, tillage or planting is called, as indeed it is, waste,” John Adams wrote extensively of the practical importance of land ownership in sustaining American liberty, a sentiment that certainly would have had the hearty approval of the crowd in attendance. Without a large middle class of landowners it is impossible to imagine the sort of citizenship that republican government demands.

A culture of widespread land ownership also helps tamp down class divisions. My host, who, in his long career, has received encomia from Nobel Prize-winning economists and Supreme Court justices, stops more than once to talk to people—a fellow rancher who is grazing cows on his land this year, another man who owns a local gravel pit, that he assures me, making sure the man is within earshot, provides top quality gravel. There’s no obvious sense of class hierarchy here, a fact aided by a high degree of cultural uniformity.

I won’t go into rhapsodies about how this is the “real America” as if urban and suburban America is somehow less real. But there is a sense here of connection with the land that has been lost to most of us today, where our only contact with food is the supermarket.

Almost two years ago, when we left California, attending an event like this would have been unthinkable. Virtually everyone I knew—all my neighbors and friends, worked in the technology business. The few who didn’t were at Stanford University, where I also worked. They came from all over the world, in a wide variety of skin tones, but in many ways it was a monoculture. In the broadest sense of the word, their tastes, politics, goals, and outlook on life were very similar. They were not bad people—just very cloistered—and many of the policies they supported caused tremendous damage that was never visible to them because, secure in the fantasyland of Silicon Valley, they never knew anyone affected by them.

Bozeman, the nearest town to where we live today, is definitely the most “new west” city in Montana, with transplants from all over the country. Yet even in our short time here, we’ve met several farmers and ranchers socially and many other friends—seemingly “new west” types when you meet them—turn out to have grown up on farms and ranches or in isolated small towns in rural Montana where they still have family. You can find some Ivy Leaguers and tech bros in Bozeman (in fact, our newly-elected Republican Governor from Bozeman founded a tech company here that he sold to Oracle for almost $2 billion), but it’s still very much the exception, not the rule.

A Deepening Divide

But the regional ag newspaper out of Billings (tagline “All the news a busy rancher has time to read”), indicates disquiet at the edge. It is clear that whether or not these ranchers are interested in politics, politics has become interested in them—and they know it. Much of the content would not be out of place in a conservative journal. The Publisher’s note, written shortly after the Super Bowl, acknowledged that “more and more people I’ve visited with have boycotted watching pro football,” combined with relief that the commercials this year were not too political.

But the comment that struck me most came from an article discussing New Jersey Senator Corey Booker recently becoming the first vegan on the Senate Agriculture committee. “Earning the title of first vegan on the Senate Ag Committee,” a reader noted, “may be widely praised by about 3% of our nation’s population—but let’s not forget, the other 97% eat meat—and hopefully will have our backs when it comes to producing it for them.”

The 97% vs. the 3% or the 99% vs. the 1%. The concerns of ranchers in rural Montana are different in form than those of disaffected urban millennials. But both groups speak to worries that a self-appointed elite has passed them by and doesn’t understand their lifestyle, their goals, and their struggles.

If we can’t address those worries seriously and respectfully in the near future, we’re going to have some big problems on our hands. Or, to quote a maxim cited in the bull auction catalog, “If you find yourself in a hole, the first thing to do is stop diggin’.’”

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Thanksgiving remains one of our few unifying traditions.

You can’t count on the state for your security.