America needs a proactive industrial policy to win the fourth industrial revolution.

Western Civilization, Chinese Style

China wants the goose that lays the golden eggs.

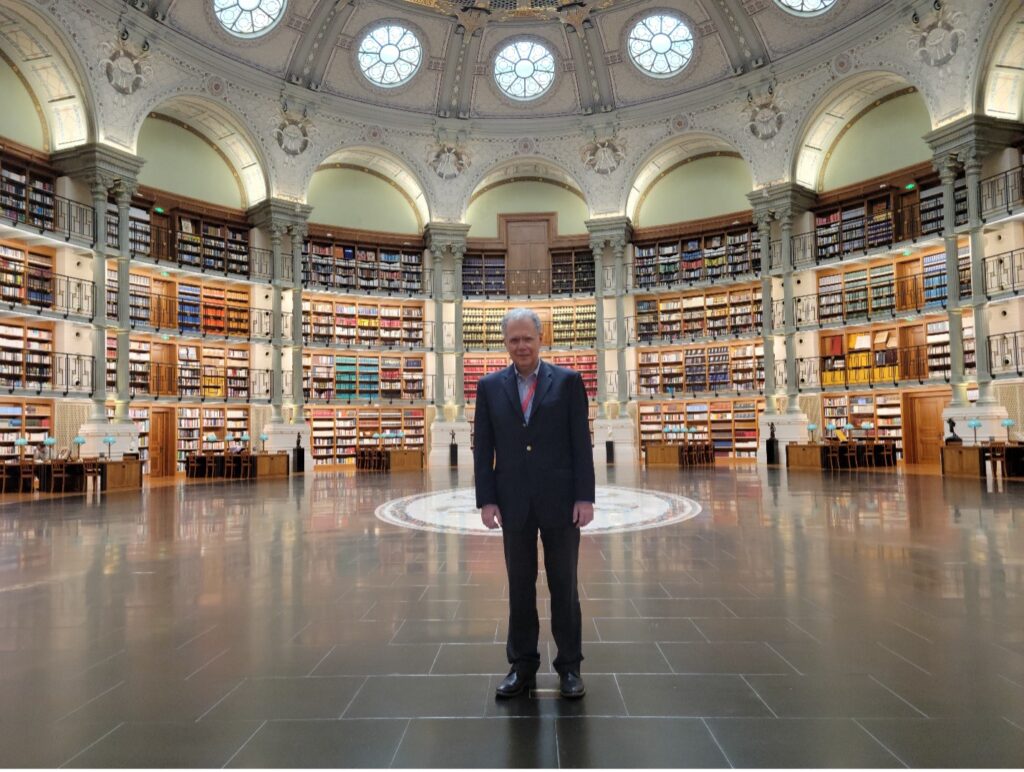

All images used in this essay are the author’s own.

China stands accused of wholesale theft of intellectual property, cited in Senate, House, and Administration reports, at a cost estimated by the FBI at $225 to $600 billion a year. Nonetheless, American corporations with the most to lose from IP theft are eager to augment their research presence in China. Take for example Intel Corp’s new chip innovation center here in Shenzhen, or Big Pharma, which lives and dies on patent protection. Nokia, one of the two main Western competitors to China’s telecom giant Huawei, conducts most of its R&D in Shanghai Bell Labs, one of the 10 largest corporate research centers in the country. The Chinese government counts 531 foreign-funded R&D centers in Shanghai alone. US companies spent $8.2 billion on R&D in China in 2019.

A visit to Huawei’s 2,000-acre campus in Shenzhen helps make sense of this cognitive dissonance, in which corporate America makes enormous bets on IP in a country that the FBI claims is stealing IP from them. The simple answer is that Chinese R&D is very good and getting better fast. More critically, Chinese IP theft isn’t simply a matter of this or that technological advancement. It’s much deeper and broader than that: it’s about claiming and replicating the source of innovation. China is engaged in what might be termed the boldest act of IP theft in world history, or to borrow a Woke expression, the most egregious act of cultural appropriation ever. It is “stealing” Western high culture.

Rising over the landscaped woodlands, lawns, and lakes of Huawei’s sprawling headquarters is the Oxhorn Campus, a newly-built city filled with reproductions of classic European architecture, housing 25,000 research and development personnel. It bears a passing resemblance to Disney’s Epcot Center, except that the buildings are real, built to scale, and occupied by people who come to work here every day. The choices are eclectic. Heidelberg is featured prominently, with a reproduction of the Marktplatz and the famous Old Bridge, plus bronze statues of Einstein, Beethoven, the Curies, Tesla, and other scientific and cultural figures.

There is a library modeled on France’s Bibliothèque Nationale with its famous dome, a German castle, a French chateau, and Italian cobbled streets. Incongruously, exercise classes filled with Huawei employees dressed in regulation gray t-shirts and black shorts puff through reconstructed 18th-century towns.

China wants the goose more than it wants the golden eggs. “Mr. Ren [Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei] believes that classical art and architecture foster creativity, which is what Huawei expects from its researchers,” explains a Huawei executive as we alight from the Swiss-manufactured light rail line that shuttles employees across the facility. The rail carriage’s retro style suits the architectural theme, although futuristic autonomous buses also glide through the Oxhorn campus.

Even more arresting are the acres of frescoes that adorn the vaulted ceilings and walls of Huawei’s Galileo Exhibition Hall, which showcases the firm’s tech products. Huawei does not allow photographs of the Galileo facility to be published, which is sad; I have seen nothing remotely like this outside the Vatican. The great gallery extends for two hundred yards in either direction, with a half-dozen grand vaults soaring 60 feet above the floor, painted by local artists in imitation of European style. The columns are decorated in something like Raphel’s Grotesque style, with a few whimsical touches. I have never seen a corporate headquarters remotely like this, nor even—outside a couple of outstanding European examples—a public building.

My interlocutor formerly danced with one of China’s main corps de ballet and plays a classical instrument, with a preference for Bach. That’s not unusual; perhaps 50 million Chinese children study classical piano and tens of millions more play orchestral instruments. China graduates more engineers than the rest of the world combined, but it also trains more classical musicians than the rest of the world combined. That is a killer combination. Not by coincidence, classical music has been the avocation of great scientists and mathematicians for the past three hundred years.

By some measures, China has overtaken the United States in scientific research—but it is difficult to know what such gauges really mean. Huawei holds 110,000 patents, and it derives substantial revenue from licenses. The company spends a remarkable 25% of gross revenues on R&D, vs 10% to 15% for leading software companies. It designs its own chipsets, for example, the Kunpeng chipset that powers its Ascend A.I. processor on Huawei’s Cloud-based AI systems. It pours billions into basic research. We will learn over time how creative Huawei’s researchers are.

Ren Zhengfei has the right idea about classical art and creativity. On the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth, I argued (following Kant’s Critique of Judgment) that Beethoven’s plasticity in time evoked an awareness of the Infinite:

The term “Beautiful” applies to finite objects that fall within our understanding: a flower, a tree, a melody. But there are natural phenomena that confront us with the infinite, which our senses cannot take in and our understanding cannot grasp….

The Sublime challenges us to conceive of something that transcends the way we process sense information. Because the Sublime demands our intellectual response, it evokes freedom: We are not the passive observer of fixed and limited phenomena, but the artist’s collaborator in the recreation of the artwork. We must lift our spiritual level to engage it.

Beethoven’s temporal transformations conjure a sense of the Sublime: “By evoking the infinite out of finite temporality, Beethoven gives us not just an impression, but rather an existential participation in freedom. The composer confounds our expectations and plays hob with our temporal perception, demanding that we follow him through warps in the space-time continuum.”

Decades ago, I taught music appreciation at a public university and music theory at a private conservatory. My non-musical students probably got something from a survey-course exposure to classical music, but the real benefits of musical study accrue over years of diligent application. The tens of millions of Chinese children who practice their instrument daily receive immersion in depth in Western culture.

At Western conservatories, Chinese students long had a reputation for technical brilliance and artistic mediocrity. The superstar pianist Yuja Wang exploded this stereotype in 2017, with the most compelling rendition ever of Beethoven’s most difficult sonata, the Op. 106 (“Hammerklavier”). As I wrote at the time, “Every Western pianist I had heard perform the work over the years, from Mieczyslaw Horszowski to Daniel Barenboim, performed it as if it were the mummified body of an uncorrupted saint. Ms. Wang got Beethoven’s joke and treated it as a grand, relaxed Mephistophelian romp, full of stops and starts, crude musical jokes, and downright bloodymindedness.”

A glance at Peking University’s philosophy syllabus should remove any doubt that China knows exactly what it is doing. China’s top university offers four undergraduate courses on Kant, including a full semester on the Critique of Judgment; Harvard by contrast offers not one (just a survey of “post-Kantian” European philosophy). Neither did Columbia when I studied there half a century ago; as a freshman I talked my way into a graduate course on Kant taught by a visiting German).

Peking University also offers a seminar on Hegel’s “Philosophy of Right,” with its celebrated exposition of civil society as the realm of freedom. We live in three spheres, Hegel argued: The family, the state, and civil society. We have no choice as to the family into which we are born, and no choice with respect to the requirements of the state (we have to pay taxes, obey laws, and serve in the army). But we choose freely to start a business, organize a sports club, join a volunteer group, and so forth. The character of the state depends on civil society; parliamentary democracies do not flourish in tribal societies, for example.

China’s elite is painfully aware of the deficiency of its civil society. For thousands of years, the Chinese empire has rested on the twin hierarchy of imperial governance and the extended family, where fealty and obligations are well defined and the scope of individual initiative is limited. It is a chauvinistic canard that the Chinese are not creative, but it is emphatically the case that the scope of individual initiative in China is constrained by the acromegalic imperial state. Classical music offers a private sphere of spiritual liberty in the abstract, a realm for the mind to play freely without impinging on politics.

Building an R&D center with copies of great European buildings, moreover, isn’t quite the same as creating those buildings in the first place. Europe created magnificent architecture in a society that honored the sanctity of the individual and the sovereignty of the human spirit. But Huawei’s Oxhorn campus is the next best thing. We cannot expect to match China’s enormous numbers of qualified personnel. However constrained China’s appropriation of Western culture may be, it nonetheless preserves some of the greatest accomplishments of the Western spirit at a time when the West itself neglects or tramples on them.

The America of John F. Kennedy could outpace China in science and technology. But that also was a country that devoted more than 10% of the federal budget to R&D, compared to just 3% today, and a White House that featured performances by Pablo Casals rather than rappers. If we abandon the spiritual sources of our creativity, we will have no one but ourselves to blame if China dominates the world economy.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Actual policymakers have to do that.

Time is pressing to turn our tech Titanic around.

What if they declared a trade war, and only one side showed up?