The Real Watergate Scandal

A myth and its legacy.

What follows is an excerpt from Nathan Pinkoski’s essay, “The Real Watergate Scandal,” from the 25th anniversary Fall 2025–Winter 2026 issue of the Claremont Review of Books.

The United States Constitution establishes a republic, not a monarchy. If an American president ever had royalist or autocratic aspirations, it would pose an existential threat to the Constitution. Numerous Americans believe that’s what made President Richard Nixon so dangerous. When House Speaker Carl Albert denounced Nixon’s “one‐man rule” in 1973, he was channeling the opinion of many at the time—and since. But removing a monarch from office is no smooth, straightforward affair. If it’s true that Nixon acted like a king, then the closest the country has ever come to regicide was the drama of Watergate. The scandal began with the arrest on June 17, 1972 of five men working for the Republican Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CRP), who were caught breaking into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee, located in the Watergate Office Building. The scandal appeared to end with Nixon’s resignation speech two years later, on August 8, 1974. The successful removal of the president took presidential authority down in its wake, condemning any president who tries to recover it as another Nixon, another monarch-in-the-making. This has itself become a scandal, a stumbling block to understanding some of the most tumultuous years in American history, when the country and its politics changed forever.

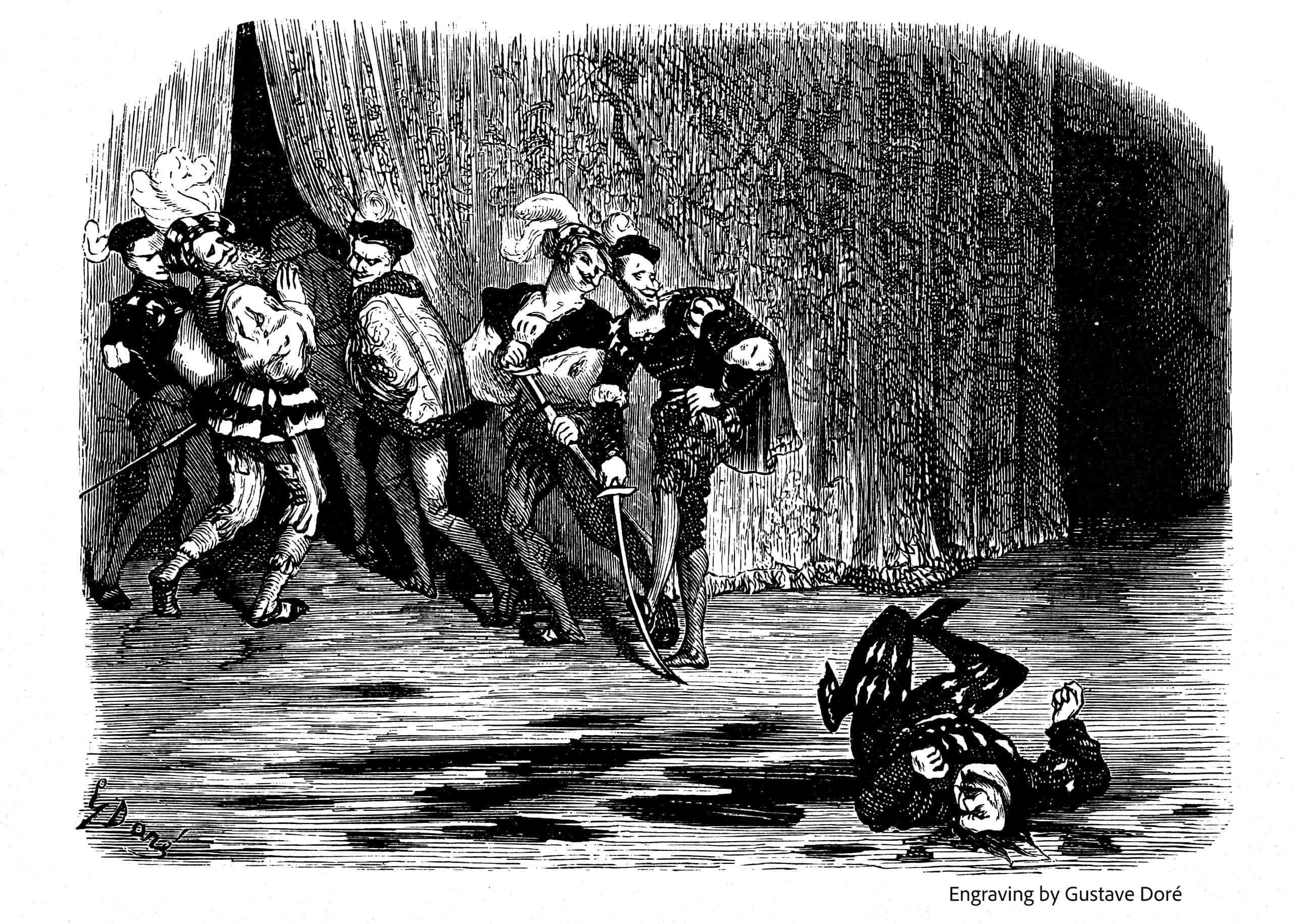

As Edmund Burke understood, regicides are a foul business, leaving in their wake a false peace as well as a contagion that continues to break apart the political and social order. In the case of the French Revolution, we at least know who brought down Louis XVI: the National Convention delegates who voted for his execution. In the case of Watergate, we don’t really know the individuals who brought down Nixon.

Instead, the events are shrouded in a pious myth. It teaches that Nixon, responsible for unprecedented crimes, deserved to be removed from office, and that in removing him, the constitutional process worked as it should. This myth—and not Nixon’s actions taken in the wake of the burglary—is the great cover-up of the last decades of the 20th century. Only now is that cover-up collapsing and the post-Watergate consensus falling apart. Only now do we see the full extent of the damage done by the collective, coordinated rage at a president who wanted to rein in unaccountable bureaucracy.

At All Costs

If the myth of Watergate can be summed up in a phrase, it’s “the imperial presidency.” Postwar liberalism’s greatest historian, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., popularized that expression at the start of Nixon’s second term. Conceived largely to attack Nixon’s centralization of foreign policy in the executive branch, the phrase came to indicate widespread presidential abuse of power, regarding Nixon as an anti-constitutional actor who subjected the American system to its ultimate trial.

And so, when, for example, on October 20, 1973, in what came to be dubbed the “Saturday Night Massacre,” Nixon fired the special prosecutor leading the Watergate investigation, Archibald Cox, the response was quick. “Good evening,” began NBC anchor John Chancellor, interrupting primetime television. “The country tonight is in the midst of what may be the most serious constitutional crisis in its history.” In the film version of All the President’s Men (1974) by Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, lionized ever since for their coverage of the scandal, their editor, Ben Bradlee, deadpans, “Nothing’s riding on this, except the First Amendment of the Constitution, the freedom of the press, and maybe the future of the country.”

When President Nixon had first been sworn into office in 1969, he hardly resembled a king or Caesar poised to destroy the Constitution. Few presidents in American history faced such vast challenges from a position of such weakness. The Vietnam War had become the longest war in American history. From the late 1960s onward, national law enforcement had to cope not just with rising crime and urban riots, but with the rise of domestic terrorism and regular bombings (at its peak in 1972, almost five a day). The goals of the civil rights movement were changing. Peaceful, color-blind co-existence was morphing into something else, as Black Panther Stokely Carmichael urged supporters to become “urban guerrillas” who would “fight to the death” in order to smash “everything Western civilization has created.” To address this domestic revolution, the state itself had also changed. The late 1960s were revealing the excesses of the national security apparatus.

Read the rest here.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

It’s a good time to remember that our Constitution is founded on the right of revolution.

Official conservatism would rather harumph about dissidence than address core issues.

The president should act in light of his understanding of the Constitution.

How Straussians interpret the founding.

The former president will be a force to reckon with in the fall.