The prognosis for free speech in America promises marked improvement.

The Party-State Media

NPR and the BBC are fully aligned with the objectives of the state.

We thank N.S. Lyons for allowing us to republish the following piece from his Substack, The Upheaval.

Yesterday National Public Radio (NPR) announced that it is leaving Twitter, after the platform “falsely labeled” it as “state-affiliated media.” This is the “the same term it uses for propaganda outlets in Russia, China and other autocratic countries,” the indignant NPR huffed. Twitter CEO Elon Musk had the label changed to “government funded,” but this was still too much for NPR, which claims that—while it does receive government funds—such a label would tarnish its “credibility” and could somehow even “endanger journalists.”

Meanwhile the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is also throwing a hissy fit over being pasted with the same label, saying it “is, and always has been, independent,” and is merely “funded by the British public.” Also complaining is Voice of America (VOA), which, despite literally being run by an arm of the U.S. federal government, the U.S. Agency for Global Media, claims that, “The label ‘government funded’ is potentially misleading and could be construed as also ‘government-controlled’—which VOA is most certainly not.”

Each outlet claims it maintains “editorial independence” from the state despite receiving government funding, and so doesn’t deserve to be called “state-affiliated.” Regardless of what you think of Musk or Twitter, this is absurd. Let’s leave aside VOA, which was literally founded to conduct information warfare abroad on behalf of the United States, first in WWII and then during the Cold War, and is therefore so obviously state-affiliated that its claims otherwise are not really worth addressing. The BBC and NPR are only marginally less obvious in being state media.

It would actually be more accurate, however, to call these outlets “Party-State” media. I’ll get into what I mean by that shortly, as I think the concept helps explain an important broader truth about how power and government operate today, and not just when it comes to the media.

First, though, let’s address the obvious: these media outlets rely on government cash. This is most egregious in the case of the BBC, with 71% of its total revenue in 2022 coming from the BBC “licence fee,” a tax currently set (by the government) at £159 ($199) a year for every British household. Paying the fee is required by law if you own and watch any TV whatsoever (not just the BBC), including streaming on online services like YouTube. Compliance is zealously enforced, with nearly 1,000 members of the public currently being prosecuted for non-payment of BBC dues per week (more than 118,000 were prosecuted in 2019 alone). Non-payment results in fines of as much as £1,000, and not paying those results in arrest, by agents of the state. There are currently British citizens in prison for not forking over their money to the BBC. About 74% of the British public would prefer not to pay this fee, but have to anyway. This is what is typically known as extortion, or theft. So the BBC is only “publicly funded” in the sense that its funds were taken from the public, forcibly, by the state.

And while the BBC claims it can operate with nearly three-quarters of its funding coming from the government (whoops, I mean “the public”) and still remain independent in its coverage, this is clearly nonsense. Any organization that relies overwhelming on a patron for its continued financial existence will do what that patron wants. Obviously. And thanks to leaked emails and WhatsApp messages we can peruse a real time record of how the government leveraged this deference during the pandemic, with, for example, an “IMPORTANT ADVISORY” email sent from senior BBC editors to reporters informing them that Downing Street was “asking” if they could please avoid using the word “lockdown” to describe shutting people in up in their homes—and thus only “curbs” and “restrictions” appeared in BBC headlines the next day. This has hardly been limited to pandemic exceptions. As one BBC inside source told The Guardian: “Particularly on the website, our headlines have been determined by calls from Downing Street on a very regular basis.”

The government has no need to tell the BBC what to write, however, merely to politely suggest, or to reach out to “correct” some “misinformation,” and the BBC makes some voluntary editorial changes, independently.

Canadian media is today another good example of how this works, what with Justin Trudeau’s government having rolled out a budget in 2019 pledging to hand out $600 million in new state subsidies to favored media companies, conveniently doing so just ahead of elections. Those determined to be “Qualified Canadian Journalism Organizations,” such as the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) got massive regulatory subsidies and tax credits; “unqualified” media got to try to compete against this cartel on their own. Understandably, Canadian media outlets therefore have a strong incentive to remain on the government’s good side. Thus when Trudeau wants something, such as to smear his opponents as Nazis, he has no need to do so himself; he need only wonder it aloud—“will no one rid me of these troublesome truckers?”—and his will be done, independently. Trudeau himself has since developed the confidence to quip in public that the media “lets us off the hook for a very good reason, because we paid them $600 million.” But interpreting this as anything more than a joke is misinformation, according to fact checking conducted by Canadian state media (sorry: “publicly funded” media).

So as Musk himself put it to an NPR reporter: “If you really think that the government has no influence on the entity they’re funding then you’ve been marinating in the Kool-Aid for too long.” (NPR unironically described this statement as Musk having “veered into conspiratorial territory.”)

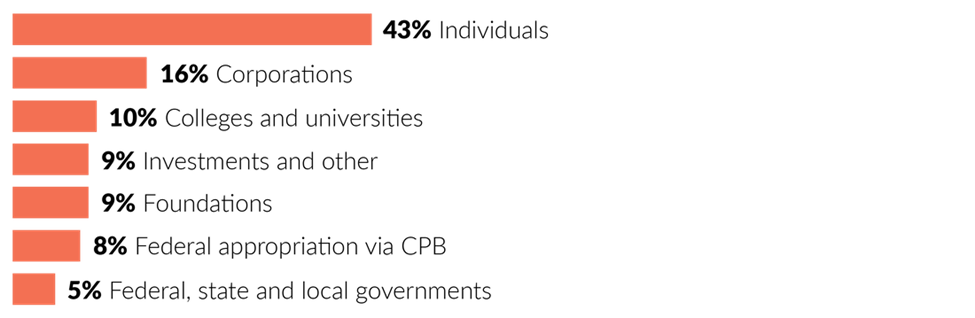

NPR also relies on government funding, though less so than their British and Canadian comrades. While NPR is loudly claiming it only receives about 1% of its money from the government, this downplays the reality by referring only the national-level organization and not to NPR’s local and affiliate radio stations, which do much of the actual work (and which then send a portion of their revenue upward). Those stations are far more reliant on government funding:

Public Radio Station Revenues (FY20):

Funnily enough, NPR in the past hasn’t been shy at all about stating (over and over again) how utterly it relies on government funding. “Federal funding is essential to public radio’s service to the American public and its continuation is critical for both stations and program producers, including NPR,” it still declares on its own website (bold in the original). “The loss of federal funding would undermine the stations’ ability to pay NPR for programming, thereby weakening the institution.”

But all this may actually obscure the more fundamental issue, which that there is in fact no clear distinction at all to be made between the state and all those “non-government” organizations (like NPR) dedicated to furthering the same agenda as the state while operating in parallel to it.

Anyone with enough experience abroad in the developing world may have heard the term “GONGO” before. A GONGO is a “Government-Organized Non-Governmental Organization.” GONGOs are set up by governments to advance their interests “independently” through “civil society,” though typically no one in the more honestly corrupt parts of the world really pretends they are actually very independent. While often taking on flourishing lives of their own after their birth, such NGOs can help accomplish various missions helpful to the state, in all kinds of ways.

The “censorship-industrial complex” exposed by the “Twitter Files” is a telling example of this utility. When Washington’s permanent administrative state, including federal government agencies like the FBI, Department of Homeland Security, and State Department, set out after 2017 to protect the American public from ever voting the wrong way again by systematically filtering their access to information, they couldn’t do this all by themselves. So instead they adopted a “whole-of-society approach” to the “War on Disinformation” and set up a thick network connecting technology and media companies, universities, and NGOs, such as the Stanford Internet Observatory, the Poynter Institute for Media Studies, and the Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media Politics and Public Policy. Many of these outfits were in turn funded by the same group of aligned “philanthropic” foundations, such as the Knight Foundation and the Open Society Foundation. (The 20% of NPR funding coming from “Foundations” and “Colleges and Universities” should also take on new meaning in this context.) As a DHS memo first made public by the journalist Lee Fang described it, the explicit strategy was to use third-party nonprofits as a “clearing house for information to avoid the appearance of government propaganda” due to their being formally independent “civil society” organizations.

But focusing only on funding in fact actually only obscures the deeper problem here. Even if NPR or the BBC took no government money whatsoever they might in reality still be aptly described as “state-affiliated.”

The People’s Republic of China operates through what is known as a “dual track” regime system. Officials are appointed to occupy positions in the Chinese national state. But parallel to the formal state hierarchy is an entire shadow edifice of positions within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) system. Every ranking official must also be a Party member in good standing, every state position has what is essentially a corresponding Party position, and often the same individual occupies both positions. For example Xi Jinping is both President of China and General Secretary of the CCP. In every case the Party position out-commands the state position. In many cases Party members hold Party positions that have no corresponding state position but nonetheless exercise tremendous power over affairs of state. Although political parties other than the CCP are tolerated, even deliberately cultivated, committed members of these parties are not allowed to occupy any positions of real power. The Party has also simultaneously set up a vast network of social organizations and other GONGOs that operate beyond the state. There is a Party cell in every major organization and corporation. In China, coordinating all these “opposition” parties and “civil society” institutions is known as “united front work.” Ideological directives distributed just within the Party system can thus seamlessly set the agenda for the whole national state. The PRC therefore cannot be described only as a “state”; it is a “party-state.”

I would argue that at this point the United States, Canada, and Britain can also be effectively described as party-states. This structure isn’t as obvious only because it hasn’t (yet) been formalized.

A single informal, oligarchic party dominates all of these countries. Transcending formal political party affiliations, this Party consists of the same class of managerial elites, united by their possession of essentially identical ideological education, core philosophical beliefs, cultural norms, material interests, and incentives. This is the Party of managerial technocracy, and every member—regardless of whether they occupy a formal government position or not—possesses a shared interest in seeing the further expansion of managerial control, of democratic power being progressively elevated out of the hands of the unwashed public and redistributed to a technocratic “expert” class (themselves). The more centralized bureaucracy, the more power of “experts” to gatekeep what is and is not “True,” the more top-down administration of every aspect of life that is imposed on the public, the more the relative power and prestige of all of these Party elites grows, whether they are political bureaucrats, academics, non-profit “activists,” or journalists. In fact even their specific national citizenship is not especially significant, since the Party transcends borders (which may be part of why we now have international meetings of “Media Ministers”). All that they need to do is uphold the continued and undivided rule of the Party.

Therefore the most critical prerequisite for an individual to hold a position of power in this system is that they absolutely must be a Party member in good standing. Those cadres who conceal heretical views, who dissent, who stray from the “Party line,” are all potential class traitors who must be immediately identified and ruthlessly corrected or purged (as the likes of Matt Taibbi, Bari Weiss, and even Musk have found). Relentlessly policing the Party ranks is even more important than suppressing the masses, since deplorable plebs aren’t likely to sneak their way into positions of institutional power that are reserved for Party members. Party unity is paramount because the Party has power.

When media like NPR want to claim “editorial independence” from state power they inevitably point to their reporters having relentlessly challenged the Trump Administration. But this ignores the signal fact of American politics since 2016: Donald Trump was elected to the nation’s highest office, but was not a Party member in good standing. All the power of the Party instantly revolted against this intrusion, causing of the all-consuming elite freak-out that ensued, has yet to subside, and will not subside until a similar oversight is deemed structurally impossible.

In such a closed party-state system very little direct coordination is necessary. Typically no editor has to be called up and told what to say. The pressure of ideological conformity easily serves this role. Even the most minute changes in what constitutes correct opinion quickly ripple out from the Party center and are incorporated into the repertoire of every cadre as each instantly repositions themselves to match the consensus Party line. General theoretical concepts (“masks work [now]”) or strategic goals (“lockdowns good, dissent should be criminalized”) are seamlessly incorporated into Party praxis (implementation and practice) without question. Frank the FBI agent and Joanna the journalist are programmed to each react the same way to the same narrative stimulus and repeat the same slogans, because each wants to avoid being shamed and to advance in status within the de facto Party hierarchy of their respective organizations. All Party institutions therefore move in sync as a united front. This is how the censorship industrial-complex coordinates what it censors. And it’s what generates the relentless tide of bewildering, bizarre propaganda and gaslighting that NPR and the BBC are now so famous for.

In this context whether or not NPR or the BBC is directly funded or managed by the state is largely irrelevant. These institutions are at this point entirely staffed by Party members, or people desperately pretending to be Party members. They have the same broader interests as the other organs of the Party, including those of the state. And so, like all Party institutions, they function in full alignment with the objectives of the state, and will never substantially challenge it. In the end NPR and the BBC are really not all that much more independent than Xinhua. They are Party-State media.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Elon Musk rules over his social media demesne as a kind of digital statesman.

Jacob Blake, Kyle Rittenhouse, and the lies we still live by.

A society that teaches its children to despise their elders will collapse.

All racism is bad, but some racism is more racist than others.

Honest, objective journalism would help restore our fracturing nation.