‘Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

The Fate of Liberty

American New Year 1777

On New Year’s Day, 1777, Robert Morris, Pennsylvania delegate to the Continental Congress wrote from Philadelphia to commander in chief of the Continental Army George Washington, who was deployed with his army in a defensive position 35 miles away near Trenton, New Jersey. Morris wrote: “The year 1776 is over I am heartily glad of it & hope you nor America will ever be plagued with such another. . . .” There were many reasons to be “heartily glad” that the year 1776 was over, chief among them the crushing setbacks and hardships that had plagued Washington’s armies since independence was declared six months before. As the year ended, despite the stunning and historic victory at Trenton the day after Christmas, there was good reason to fear that Washington’s army would dissolve and with it any hopes for the American Cause.

One New England Regiment was representative of the desperate state of the army on which the fate of the American Revolution depended. In a remarkable document, a sergeant in that regiment reports what he observed on New Year’s Eve. “Our troops,” he writes, were in “destitute and deplorable condition.” Neither the horses nor the men had shoes.

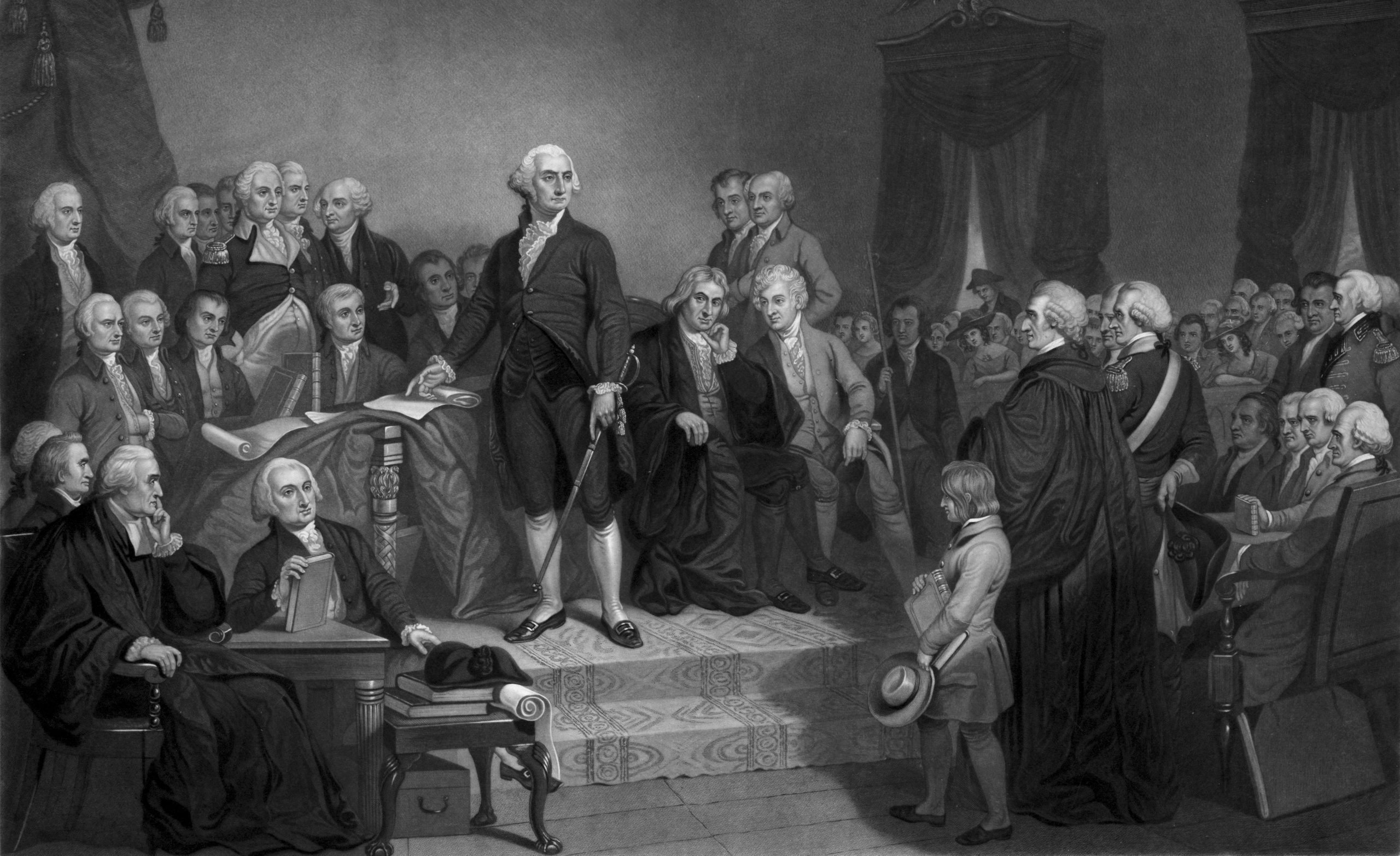

On the last [day] of December, 1776, the time for which I and the rest of my regiment had enlisted expired. At this trying time General Washington . . . ordered our regiment to be paraded, and personally addressed us, urging that we should stay a month longer. He . . . told us that our services were greatly needed, and that we could now do more for our country than we ever could at any future period; and in the most affectionate manner entreated us to stay. The drums beat for volunteers, but not a man turned out. The soldiers worn down with fatigue and privations, had their hearts fixed on home, . . . and it was hard to forego the anticipated pleasures of the society of our dearest friends.

He continues, painting a vivid picture of Washington at this critical moment:

The General wheeled his horse about, rode in front of the regiment, and addressing us again said, “My brave fellows, you have done all I asked you to do, and more than could be reasonably expected; but your country is at stake, your wives, your houses, and all that you hold dear. You have worn yourselves out with fatigues and hardships, but we know not how to spare you. If you will consent to stay only one month longer, you will render that service to the cause of liberty, and to your country, which you probably never can do under any other circumstances. The present is emphatically the crisis, which is to decide our destiny.”

The drums beat the second time, and after talking among themselves, finally a few soldiers stepped forward, soon followed “by nearly all who were fit for duty in the regiment, amounting to about two hundred volunteers.”

The sergeant records that “About half of these volunteers were killed,” just three days later, in the battle of Princeton, in which Washington’s army achieved another historic victory. Others “died of the small-pox soon after.” It is impossible to know what these young heroes might have done with the lives they sacrificed at that moment for their country and the cause of liberty. To the extent that it is given to us to judge such things, it certainly is conceivable that their sacrifices rendered a greater service to their country and the cause of liberty than any they could have rendered at a future period. One reason for such a judgment is that without their sacrifices, there may have been no future for their country or its cause. Many sober-minded students of these things believe what they did in those last days of 1776 and first days of 1777 made a decisive difference in the history of the world. There is no way they could have known that when they stepped forward on New Year’s Eve rather than going home to their families and dearest friends. There is no way Washington could have known it, when he persuaded them to stay with him and offer their lives for one more month.

Looking ahead to 2023 and beyond, we can be as sure as Washington, looking ahead to the New Year 1777 and beyond, that the cause of our country—and the fate of liberty in the world—is in our hands. Where else would you want it to be?

Happy New Year!

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Remarks from National Conservatism II

"These are the times that try men's souls."