And is it good?

The Closing of the Internet Mind

The definition of online freedom has been depressingly constricted over the last thirty years.

You have surely heard that your search results on Google (with 92 percent share of the search market) reflect not your curiosities and needs but someone or something else’s views on what you need to know. That’s hardly a secret.

And on Facebook, you are likely inundated by links to official sources to correct any errors you might carry in your head, as well as links to corrections to posts as made by any number of fact-checking organizations.

You have likely also heard of YouTube videos being taken down, apps deleted from stores, and accounts being canceled across a variety of platforms.

You might have even adjusted your behavior in light of all of this. It is part of the new culture of Internet engagement. The line you cannot cross is invisible. You are like a dog with an electric shock collar. You have to figure it out on your own, which means exercising caution when you post, pulling back on hard claims that might shock, paying attention to media culture to discern what is sayable and what is not, and generally trying to avoid controversy as best you can in order to earn the privilege of not being canceled.

Despite all the revelations regarding the Censorship Industrial Complex, and the wide involvement of government in these efforts, plus the resulting lawsuits that claim that this is all censorship, the walls are clearly closing in further by the day.

Users are growing accustomed to it, for fear of losing their accounts. For example, YouTube (which feeds 55 percent of all video content online) allows three strikes before your account is deleted permanently. One strike is devastating and two existential. You are frozen in place and forced to relinquish everything–including your ability to earn a living if your content is monetized–if you make one or two wrong moves.

No one needs to censor you at that point. You censor yourself.

It was not always this way. It was not even supposed to be this way.

It’s possible to trace the dramatic change from the past to present by following the trajectory of various Declarations that have been issued over the years. The tone was set at the dawn of the World Wide Web in 1996 by digital guru, Grateful Dead lyricist, and Harvard University fellow John Perry Barlow, who died in 2018.

Barlow’s Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace, somewhat ironically written in Davos, Switzerland, is still hosted by the Electronic Frontier Foundation that he founded. The manifesto waxes lyrical about the liberatory, open future of internet freedom:

Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.

We have no elected government, nor are we likely to have one, so I address you with no greater authority than that with which liberty itself always speaks. I declare the global social space we are building to be naturally independent of the tyrannies you seek to impose on us. You have no moral right to rule us nor do you possess any methods of enforcement we have true reason to fear.

Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed. You have neither solicited nor received ours. We did not invite you. You do not know us, nor do you know our world. Cyberspace does not lie within your borders. Do not think that you can build it, as though it were a public construction project. You cannot. It is an act of nature and it grows itself through our collective actions.

And so on it went with a heady, expansive vision–tinged perhaps with a dash of sixties utopian anarchism–that shaped the ethos which drove the building of the Internet in the early days. It appeared to a whole generation of coders and content providers that a new world of freedom had been born that would shepherd in a new era of freedom more generally, with growing knowledge, human rights, creative freedom, and borderless connection of everyone to literature, facts, and truth emerging organically from a crowd-sourced process of engagement.

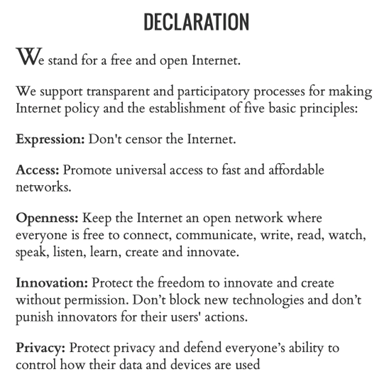

Nearly a decade and a half later, by 2012, that idea was fully embraced by the main architects of the emergent app economy and the explosion of smartphone use across the world. The result was the Declaration of Internet Freedom that went live in July of 2012 and garnered a great deal of press attention at the time. Signed by the EFF, Amnesty International, Reporters Without Borders, and other liberty-focused organizations, it read:

To be sure, it was not quite as sweeping and visionary as the Barlow original but maintained the essence, putting free expression as the first principle with the lapidary phrase: “Don’t censor the Internet.” It might have stopped there, but given the existing threats coming from growing industrial cartels and the stored-data marketplace, it also pushed openness, innovation, and privacy as first principles.

Again, this outlook defined an era and elicited broad agreement. “Information freedom supports the peace and security that provides a foundation for global progress,” said HIllary Clinton in an endorsement of the freedom principle in 2010. The 2012 Declaration was neither right-wing nor left-wing. It encapsulated the core of what it meant to favor freedom on the Internet, exactly as the title suggests.

If you go to the site internetdeclaration.org now, your browser will not reveal any of its contents. The secure certificate is dead. If you bypass the warning, you will find yourself forbidden from accessing any of the contents. The tour through Archive.org shows that the last living presentation of the site was February 2018.

This occurred three years after Donald Trump publicly advocated that “in some places” we have to talk about “closing up the Internet.” He got his wish, but it came after him personally following his election in 2016. The very free speech about which he made fun turned out to be rather important to him and his cause.

Two years into the Trump presidency, precisely as the censorship industry started coalescing into full operation, the site of the Declaration site broke down and eventually disappeared.

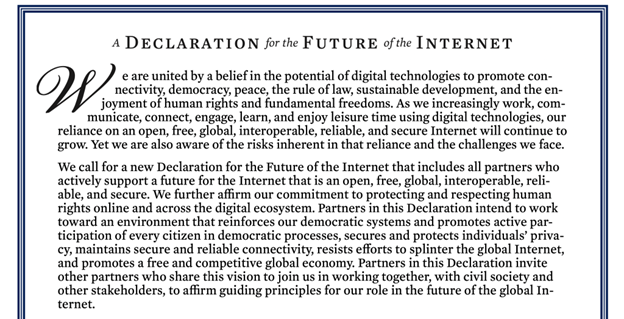

Fast forward a decade from the writing of the Internet Declaration of Freedom. The year is 2022 and we had been through a rough two years of account takedowns, particularly against those who doubted the wisdom of lockdowns or vaccine mandates. The White House revealed on April 22, 2022 a Declaration for the Future of the Internet. It comes complete with a parchment-style presentation and a large capital letter in old-fashioned script. The word “freedom” is removed from the title and added only as a part of the word salad that follows in the text.

Signed by 60 nations, the new Declaration was released to great fanfare, including a White House press release. The signatory nations were all NATO-aligned while excluding others. The signatories are: Albania, Andorra, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cabo Verde, Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Estonia, the European Commission, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Kenya, Kosovo, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Maldives, Malta, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Moldova, Montenegro, Netherlands, New Zealand, Niger, North Macedonia, Palau, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, Trinidad and Tobago, the United Kingdom, Ukraine, and Uruguay.

The core of the new declaration is very clear and represents a good encapsulation of the essence of the structures that govern content today: “The Internet should operate as a single, decentralized network of networks – with global reach and governed through the multistakeholder approach, whereby governments and relevant authorities partner with academics, civil society, the private sector, technical community and others.”

The term “stakeholder” (as in “stakeholder capitalism”) became popular in the nineties as distinct from “shareholder” meaning a partial owner. A stakeholder is not an owner or even a consumer but a party or institution with a strong interest in the outcome of the decision-making by the owners, whose rights might need to be overridden in the broader interests of everyone. In this way, the term came to describe an amorphous group of influential third parties that deserve a say in the management of institutions and systems. A “multistakeholder” approach is how civil society is brought inside the tent, with financing and seeming influence, and told that they matter as an incentive to woke-wash their outlooks and operations.

Using that linguistic fulcrum, part of the goal of the new Declaration is explicitly political: “Refrain from using the Internet to undermine the electoral infrastructure, elections and political processes, including through covert information manipulation campaigns.” From this admonition we can conclude that the new Internet is structured to discourage “manipulation campaigns” and even goes so far as to “foster greater social and digital inclusion within society, bolster resilience to disinformation and misinformation, and increase participation in democratic processes.”

Following the latest in censorship language, every form of top-down blockage and suppression is now justified in the name of fostering inclusion (that is, “DEI,” as in Diversity [three mentions], Equity [two mentions], and Inclusion [five mentions]) and stopping dis- and mis-information, language identical to that invoked by the Cybersecurity Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and the rest of the industrial complex that operates to stop information spread.

This agency was created in the waning days of the Obama administration and approved by Congress in 2018, supposedly to protect our digital infrastructure against cyberattacks from computer viruses and nefarious foreign actors. But less than one year into its existence, CISA decided that our election infrastructure was part of our critical infrastructure (thereby asserting Federal control over elections, which are typically handled by the states). Furthermore, part of protecting our election infrastructure included protecting what CISA director Jen Easterly called our “cognitive infrastructure.”

Easterly, who formerly worked at Tailored Access Operations, a top secret cyber warfare unit at the National Security Agency, coined the queen of all Orwellian euphemisms: “cognitive infrastructure,” which refers to the thoughts inside your head. This is precisely what the government’s counter-disinformation apparatus, headed by people like Easterly, are attempting to control. True to this stated aim, CISA pivoted by 2020 to become the nerve center of the government’s censorship apparatus–the agency through which all government and “stakeholder” censorship demands are funneled to social media companies.

Now consider what we’ve learned about Wikipedia, which is owned by Wikimedia, the former CEO of which was Katherine Maher, now slated to be the head CEO of National Public Radio. She has been a consistent and public defender of censorship, even suggesting that the First Amendment is “the number one challenge.”

The co-founder of Wikipedia, Joseph Sanger, has said he suspects that she turned Wikipedia into an intelligence-operated platform. “We know that there is a lot of backchannel communication,” he said in an interview. “I think it has to be the case that the Wikimedia Foundation now, probably governments, probably the CIA, have accounts that they control, in which they actually exert their influence. And it’s fantastic, in a bad way, that she actually comes out against the system for being ‘free and open.’ When she says that she’s worked with government to shut down what they consider ‘misinformation,’ that, in itself, means that it’s no longer free and open.”

What happened to Wikipedia, which all search engines privilege among all results, has befallen nearly every prominent venue on the Internet. The Elon Musk takeover of Twitter has proven to be aberrant and highly costly in terms of advertising dollars, and hence elicits vast opposition from the venues that are on the other side. That his renamed platform X even exists at all seems to run contrary to every wish of the controlled and controlling establishment today.

We have traveled a very long way from the vision of John Perry Barlow in 1996, who imagined a cyberworld in which governments were not involved to one in which governments and their “multi stakeholder partners” are in charge of “a rules-based global digital economy.” In the course of this complete reversal, the Declaration of Internet Freedom became the Declaration for the Future of the Internet, with the word freedom consigned to little more than a passing reference.

The transition from one to the other was–like bankruptcy–gradual at first and then all at once. We’ve traveled rather quickly from “you [governments and corporate interests] are not welcome among us” to a “single, decentralized network of networks” managed by “governments and relevant authorities” including “academics, civil society, the private sector, technical community and others” to create a “rules-based digital economy.”

And that is the core of the Great Reset affecting the main tool by which today’s information channels have been colonized by the corporatist complex.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The Beatles and AI.

A skeptical observer goes looking for AI bias.