tfw the dating app is creepier than the date.

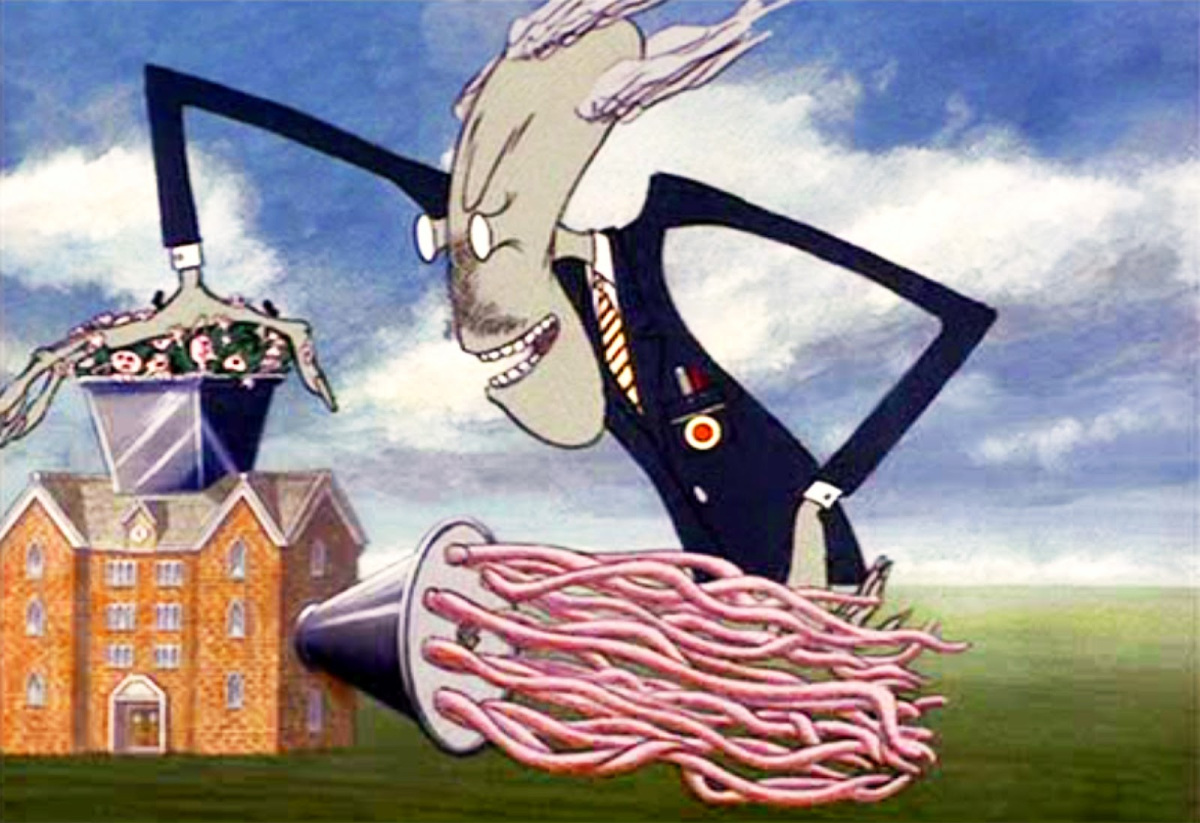

The Clear Pill, Part 2 of 5: A Theory of Pervasive Error

The evolutionary architecture of distributed despotism

This essay is the second in a five-part series. Each part stands alone, but we welcome you to read part 1 here.—Eds.

Pervasive error is any systematic and significant distortion of thought that impacts the whole discourse of a civilization.

Folk superstitions do not qualify. Fashion flows downward from social elites. Genuine pervasiveness must compromise the elites.

Elites also disproportionately participate in governance. In historical cases of pervasive error, we often see a sovereign etiology. We can expect our theory to somehow touch on power and the state.

Which is as far as we should go in expecting. We can only build a useful theory of pervasive error by working carefully forward from axiomatic principles, not backward from observed reality—thinking logically, not scientifically.

I know this is weird. Let’s start by justifying this unconventional methodology.

The wrong way to think about pervasive error

When exploring what we think may be pervasive error, our reflex is to reason inductively, from phenomenon to proximate cause to ultimate cause—like a criminal investigation, at least on TV.

Since we live in a scientific society, thinking scientifically (or trying to) is always our first reflex. This alone suggests that inductive investigation of pervasive error is fruitless. Error vulnerable to the normal response would not be pervasive.

In case this is too clever, let’s imagine a best-case scenario.

Blessed by a sudden inheritance, you fund professional parallel investigations of many plausible errors, all performed to the most thorough forensic standards. You obtain secret documents galore.

And you get striking positive results. Just amazing stuff. Bigfoot killed JFK. And that’s just the start…

You start putting out this material. Alex Jones, Oliver Stone, and John McAfee come to your house. They stage an intervention. They’re all like: man, we love you. You gotta cut back on the DMT.

But you’re completely sober. You have simply blown their little minds. You must press on…

And what does this mindblowing success buy you? You have learned only one thing: that pervasive error is real. Weren’t you already pretty sure of that? So what have you learned at all?

Are you any closer to finding one simple cause for all these anomalies—to explaining them? Why did Bigfoot kill JFK? Do you actually have any kind of positive history at all? Since you weren’t looking for one, you probably didn’t find one.

The normal temptation is to stop at some contradiction, some rip in the good blue canvas of the sky, and seek no cause at all—or worse, seek cheap, flashy causes of little or no veracity. Evidence is not understanding. Evidence is only a question. A question is not a description. A mystery is not a history.

By investigating backward, you end up just detecting pervasive error over and over again. You become a car alarm. Perhaps you expect this rite to summon some higher power. It will certainly not summon the police.

Your results are not even useful for evangelism. Before it, the infidels were blind; they thought everything was fine. Or worse—they thought you were the problem. And after? Were you the first to lead this horse? Wouldn’t he have already started drinking?

The horse is already in the water, to his hocks; you will drown him before he drinks; before that, he will drown you. This is not the way.

The right way to think about pervasive error

So let’s avoid the factual question of whether modern pervasive error exists. Instead we’ll ask a theoretical question: if pervasive error did exist, what would it look like? How would it work? What would we expect its effects to be?

A well-formed answer is a constructive proof. We reason forward—from ultimate cause, to proximate cause, to phenomenon. The way to explain error is to design error.

Once such a design for error is clearly presented, anyone can compare it to the reality they think they see around them. If they see a match, they have an explanation.

If not—maybe there is some other explanation. Or maybe there is no error at all. In the end, everyone makes this call alone. Your horse is a horse. Eventually he will get thirsty.

Dissecting the platypus

Before us lies a hard problem. Let’s start with some practice.

The living need gentle handling. The living resist philosophy. History is a cadaver; we can slice it as we please. Even if all we have to dissect is a chimp, a dog, even a platypus, there is no better training.

One recent and straightforward example of pervasive error is the Gleichschaltung—perhaps “track-aligning” would do, or just “coordination”—of the public minds of totalitarian regimes like the Third Reich and Soviet Union.

In both Nazi Germany and the USSR, the public mind was under the administrative control of the regime. Every idea that opposed the state was opposed by the state.

These were jungle states. What other law does the jungle decree? As Stalin said: “ideas are more dangerous than guns. We do not let our enemies have guns; why should we let them have ideas?”

You may have seen some arguments for idea control lately—each some soft-lipped version of this. Since Stalin couldn’t be more right, it’s unsurprising to see his logic resurrected.

But the systematic annihilation of seditious truths is only the simplest form of pervasive error in the twentieth-century total state. Gleichschaltung is not censorship; not just a Boolean function. The words on the page are not merely cut or blacked out. Power does not only delete the text. Power edits it.

In the track-aligning total states, power bent every thought that could be bent to serve it. The mark of the Orwellian state is not just the absence of truth but its displacement by lies. As the lies are optimized, they grow increasingly alike; reality, as in the late Soviet Union, becomes one dirty, gray delusion.

A puzzle in authoritarian track-aligning

One puzzle in the study of pervasive error in the total states is the wide variance in their morbidity and mortality. Sometimes the condition is quite lethal; in other cases, much milder.

One extreme data point is the Lamarckian biology of Lysenko. How can even biology be politicized? For Lysenko, education had to vanquish nucleotides, even in wheat—after all a mere edible cousin of the new Soviet man.

At least according to Wikipedia, not known for its anticommunist venom, millions died in the famines of Lysenkoist agriculture—driven by a political edit of biology—an idea more dangerous than a hydrogen bomb.

And yet we see the same central control over public opinion in other dictatorships, like today’s China or Singapore or even Tudor England, all obviously far more benign. Not only are their atrocity numbers way below mid-century standards, the degree of brain damage they inflict on the public mind is also much lower.

Even the artistic output of the Elizabethan era is remarkable. Yet Elizabeth believed no less in “free speech” than Xi Jinping.

It’s not that hard to explain this puzzle. When we observe the Holocaust, Gulag, Cultural Revolution, etc., we observe not just the total state, but the total state in a state of total war.

Stalin and Mao’s regimes committed epic atrocities outside literal wars, but they form the exception that proves the rule. During their eras of great massacre, the Leninist regimes were always psychologically in a state of civil war.

Yet no one should overrate the safety of any demented peace. War always has a cause. That cause seldom seems sensible in retrospect, even for the winner and always for the loser.

But Gleichschaltung does not wait for any war. By 1935, Victor Klemperer’s cat magazine is already all about the “German Cat”. Everything in German society that can be Nazi has to be Nazi. Otherwise, for most Germans, prewar life is still mostly normal. Germans in 1935 certainly do not consider themselves at war.

Absence of mass murder does not prove absence of mass madness. The latter seems necessary, but not sufficient, for the former. This should not be read as a reassuring discovery.

It’s a cliché to connect the Holocaust to the “German Cat”. The jaundiced must beware—clichés often turn out to be perfectly good history. And the dissenter is excused not one single error. Yes: political distortion of the public mind is quite dangerous. It is also normal and ubiquitous. Be careful!

Yet our hips shall grow no poison spurs

America is a liberal democracy. There is no such mass madness here. Nor can there be. Our cat magazines won’t sprout swastikas and start ranting about the purity of the feline race.

Thanks to the deep strength of America’s democratic institutions, its politicians will never be able to hijack the government, let alone the public mind. Elect President Hitler, and he would have no tools to make an American Gleichschaltung happen.

What exactly would he do? Whom would he use to do it? When we look for the structures and tools which all authoritarian regimes, Elizabethan, Stalinist or Byzantine, use to manage the public mind, we just don’t see them here. There is no Goebbels and no Ministry of Public Enlightenment. There are no poison spurs.

This cadaver remains a platypus. Like our patients, the platypus is a mammal with a liver. But we need not check our patients for inflamed venom glands. So we’re safe from pervasive error, right? Well—there is another possibility. It seems unlikely, but—

The Jesus nut

Logically, either liberal democracies are inherently free from pervasive error or some other mechanism can cause pervasive error in liberal democracies.

Liberal democracies have no dictator, no center, and no point of coordination. We’re looking for a mechanism which could cause pervasive error without central coordination: Gleichschaltung without Goebbels.

In the 21st-century Western model of government, elite consensus is set by a market for ideas. This consensus narrative drives public policy, which exists within the reality of the consensus. If this market somehow malfunctioned…

Let’s posit that a normal First World civil service will always implement reasonable policy relative to the truth in which it operates. Yet if the market for ideas fails, and generates a delusional narrative, policies that are competent and reasonable within this illusion may prove incompetent and unreasonable in reality.

Let’s focus, therefore, on the integrity of the public narrative—which is generally developed outside the civil service proper.

On a helicopter there is a part called a “Jesus nut,” because it holds the rotor to the driveshaft. This little steel ring is all that stands between you and the next world. In the modern democracies, markets for truth perform a comparable function. They are all that stand between us and Orwellian mass delusion, homicidal or otherwise.

Anything this important is in a very real way sacred. And indeed many seem to engage their spiritual instincts with these markets. This is understandable but erroneous. Don’t pray to the Jesus nut—inspect it for cracks.

A market for ideas is a machine. The purpose of the machine is to reject error and discover truth. The presence of pervasive error in the output tray of the machine indicates malfunction. This malfunction is an engineering failure and can be debugged as such. No mystical sentiment at all needs to be engaged.

Debugging your truth market

Suppose your truth market, once an infallible oracle, is spitting out buggy truths. Sensible plans made within its narrative seem to always fail, often while idiotic plans that contradict it succeed. While you don’t have an isolated parallel market to test it against, you suspect your bureaucrats may be driving in Vegas with a map of Reno.

It is always better to debug forward. What could be causing such a bug? How can a free marketplace of ideas, uncoerced by any ministry, still generate pervasive error? Let’s work systematically through all the ways the device could fail.

The most obvious and common failure mode in any truth machine built on the wisdom of crowds is a failure in crowd quality. Fortunately, our democracy has this problem covered. But let’s step through the code anyway.

A marketplace of ideas is a Darwinian system; it evolves what it selects for; it selects for the collective taste of its audience. A critical consensus is only as good as the critics it’s made of.

Magical thinking in this space is common. Crowds can combine and purify knowledge they have, not summon knowledge they lack. A crowd of random farmers will do a great job of assessing the weight of a bull; less so of assessing the contribution of a physics paper.

Mastering somehow its egalitarian qualms, our society has made a beautiful exception for the tyranny of prestige and the rule of experts. It never asks farmers what they think of physics papers. The crowd quality problem is a real problem, but a solved one—mostly.

20th-century democracies took a simple approach to ensuring the quality of their truth markets: they separated public opinion into two tiers, informed and instructed. In many ways this sensible architecture, roughly as old as the New York subway, is still functioning perfectly as designed.

Informed public opinion is the consensus of the upper tier: the best generalists, who only trust the best experts; therefore, the best experts themselves. Instructed public opinion, in the lower tier, goes to school and then watches the news, receiving a basic but lifelong education in informed opinion.

Many kinds of instructional failures can interrupt this process. As we said at the start, these don’t concern us here. We are only interested in errors in the expert consensus—not failures to communicate that consensus, legion though these are.

This clarifying simplification excludes all kinds of low-grade superstitious nonsense. It is not news that most people are superstitious. It is news if the vaccine against this virus, while effective, is contaminated with a different virus.

Therefore we reiterate our focus on the elite, the consensus of experts, the highest-talent, highest-prestige, top tier idea markets. The set of forces that can distort these markets is smaller and more interesting. And ideas flow down from them, not up to them. And there is no shortage at all of raw human talent, present or projected, amongst this upper cadre.

This is not to deny the existence, prevalence, or even danger of popular superstitions. Such superstitions are always best fought with the truth. And even the most bigoted elitist must admit that sometimes, the peasants are just too dumb to be fooled.

Other failure modes in narrative markets

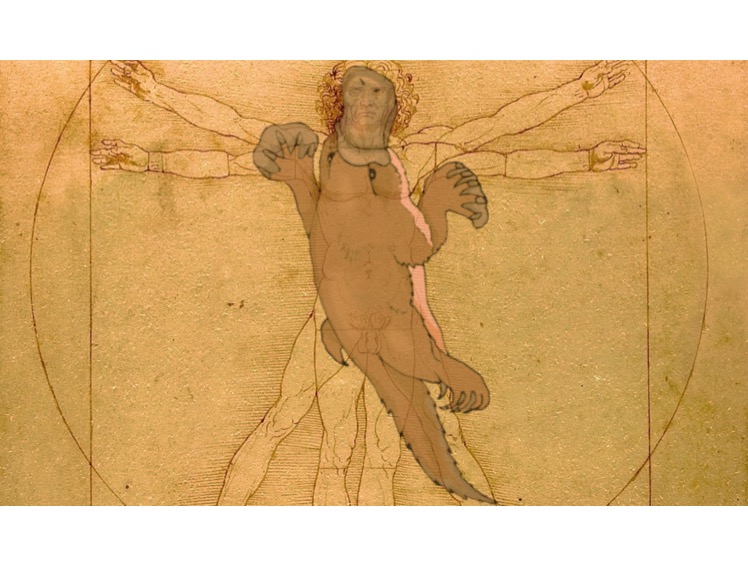

Ideas in a marketplace reproduce, mutate, and are selected. They’re Darwinian systems: designed to evolve truth. Darwinian systems are amazing. They don’t evolve what you want. They evolve what they select for: lion or tick, platypus or man.

Obviously, we want our truth market to evolve truth. What is it actually selecting for?

Every idea market is an aesthetic device. It selects for the most beautiful ideas—according to the taste of its audience. A market measures desire; desire is beauty in action. And by measuring beauty we measure truth, because truth (like my man Keats said) is beautiful.

Seen from an aesthetic perspective, every idea is a story. A marketplace of ideas is a market for stories. An idea can be any kind of story, factual or fictional; even a song or a film. All creative markets are affected by the phenomena we will describe.

But the most important idea markets are those which claim to tell a story, both true and truly illustrative, about the real world. Abusing English only slightly, we may term these histories. The definition is broad enough to include all of science—or, as once it was known, natural history.

Our consensus narrative of reality is the output product of the machine which is our market for beautiful histories. From the perspective of our collective epistemic security, the integrity of this mechanism is of the highest possible importance.

It is easy to see the exploitable vulnerability. Is a market for beautiful histories always a market for veracious histories? Yes, because truth is beautiful and lies are ugly. And—no, because other qualities might also be beautiful.

These qualities cannot cancel the Keats effect. But if they could overpower it, the result would be a beautiful lie.

An idea market can only measure truth by measuring beauty. If beauty is not truth, we assume, beauty is truth plus white noise. Given a sufficiently large audience of high average quality, these individual quirks of taste will cancel out, leaving only the consistent, high-quality truth promised in the brochure.

This assumption had better be true! If deviations from truth are not white noise, but their own coherent signal, averaging will not filter them out at all. These signals will pass through the market and emerge in the output, competing with truth.

Any such competing aesthetic signal is an attack vector on the integrity of any truth market. Only beauty can be measured. Any divergence between truth and beauty can be exploited.

Competing aesthetic signals are why, even once some crowd-selection mechanism (typically some kind of career tournament) filters for almost magical levels of human talent, the wisdom of crowds still isn’t magic.

How pretty lies work

Let’s call any source of beauty that’s unrelated to truth an aesthetic tilt. So we can speak of a tilted truth market, which risks producing not true histories but just pretty lies. Let’s look a little closer at how pretty lies work.

Fiction never parades itself openly in the history section. A lie is not a fiction; it pretends to be true. All the tilt in the world cannot make a truth market endorse a naked fiction.

Of course, some people are sociopaths. They actually find lies inherently pretty, useful, or both. Sociopaths are rare and hard to wrangle, and it is hard to imagine a pure audience of them. There are always enough sociopaths to fill a niche, never enough to fill a room. So it is hard for sociopaths to sway a market. (If you imagine that there is some party, tribe, class, or nation of sociopaths, this is very sad and you should stop.)

Truth is inherently beautiful. Lies are inherently repulsive. A market for histories works by following this aesthetic slope toward truth and away from lies. A healthy truth market is a skeptical market; it loves nothing more than exposing lies by expounding truths.

A market for histories works by using its critics’ aesthetic attraction to truth to distinguish truth from error. The mirror image of this aesthetic is the repulsive quality of deceit.

Yet skepticism itself, though logical, is an aesthetic process. The skeptical process, implemented by the brain, must still be inspired by the nose. We always start by smelling the lie.

Pretty lies—exploits in the market for truth—succeed by disabling our skeptical defenses. The converse of a pretty lie is always an ugly truth. If there is no net aesthetic repulsion to the pretty lie, and no net aesthetic attraction to the ugly truth, the two have found a level field—and either can win.

Other beautiful qualities

We now have a specific target profile: beautiful qualities other than truth. A pretty lie is a bomb. Aesthetic tilts are its explosives.

An aesthetic tilt is always and everywhere an emotion. Even the most erudite of experts are no Vulcans; they feel the same emotions, sporadic IQ-linked autism aside, as all other humans. Experience and intelligence are at most peers of emotion, never its masters.

Let’s explore two qualities that can aesthetically tilt truth markets. They’re both emotions. We’ll use the Greek words for them: thymos and pistos. We’ll call the stories that evoke them thymotic anthems and pistoic formulas.

In case this is too much Greek for one meal, thymos is somewhere between ambition, honor, and vanity, and pistos between loyalty, fidelity, and servility. And the two, though logically distinct, are closely related. As we’ll see, most real exploits use both.

Nine times out of ten, show me a malfunctioning truth market, and I’ll show you an output tray clogged with sticky anthems. Some of these anthems will be good and sweet and true; all of them will be sweet. Our political sweet tooth is the crack in the Jesus nut.

Yet sweetness is no inherent vice. We need constant reminders that our competing aesthetic signals are not opposed to truth. They are only unrelated to truth. Sometimes, they even align perfectly with it.

Probably there are as many pretty truths as pretty lies; possibly there are more; the market will embrace them more avidly than they already deserve. Everyone has some friend who deserved to succeed and did—but not because they deserved to. Whatever. The real issue is those who win though they deserved to lose.

Thymos: the desire to matter

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away—in 1936, to be more exact—some dude named Dale Carnegie wrote a book called How to Make Friends and Influence People. Mr. Carnegie’s little book outsold the Bible for years, so maybe there was something to it.

Perhaps the most important principle of the book—which it’s not unfair to call Carnegie’s law—is that people like to feel important. To make people like you, make them feel important. Con men know it well.

Thymos is the natural human desire to be important. Power and importance are synonyms; no one important is not powerful; no one powerful is not important.

The Greeks divided the soul into three parts. Let’s call them logos, eros, and thymos: reason, sexual desire, and political desire. Reason is peer, not master, to these two fundamental needs.

The public mind seems mostly safe from eros, a private urge. Could we imagine a lascivious regime? History has here and there flirted with this hellish vision. But eros will always make a good analogy for its fellow lust.

For thymos is ubiquitous today. We see it in everyone who wants to “change the world” or “make an impact”, or simply to matter. Thymos is meaning. The desire for meaning is ambition, a universal human instinct.

An anthem is any story that satisfies thymotic desire—a story that makes you feel important. Carnegie’s law tells us that people will naturally find anthems beautiful.

Four anthemic themes

As literature, the anthem is a genre, like romance or noir. While an infinite number of romance novels can be produced, the entire genre is built on a quite finite list of themes.

The same is true for the anthem. Let’s look at four anthemic themes: victory, punishment, rebellion, and largesse. This set may or may not be complete.

Victory is the theme of taking power. An anthem of victory is a tautology. If winning isn’t important, it isn’t winning. If it is, it leaves you more powerful than before.

Punishment is the theme of enforcing power. An anthem of punishment is an excuse for cruelty. What could be sweeter?

Any punitive act, even symbolic, builds strength and confidence in the punisher, while humiliating and weakening the victim. There is little a chimpanzee enjoys more than forcing another chimp to suffer. Our cousins may share a sense of right and wrong. Surely, as they bite off some rival’s balls, they feel they are imposing justice. They certainly feel important.

Rebellion is the theme of disrupting power. To destroy another’s power is inherently a demonstration of power; to use or show power is to gain it. The disruptor need not hope to gain, nor even be a subject of the power. Rebelling from the inside is insanely dangerous. Helping other folks rebel is almost as exciting, and a lot safer.

Largesse is the theme of building power. Power is made of social obligations. The way to build social obligations is to help out other folks for free—in cash or in kind.

Suppose you transfer some value to another person. If the transfer fulfills or creates a legal obligation, you are doing business. If not, you are a patron.

Where largesse is infrequent, unpredictable and unnecessary, the obligation it creates is merely social. Once largesse is regular and necessary, the bond is also economic. These bonds blend fluidly together into an instinctive patron-client relationship.

Even the English word “lord” comes from the Saxon hlaford, or “loaf-guard.” Lord is he who secures your carbs. To be strong is to have an army. To rise, become a loaf-guard; who feeds an army, commands an army.

A tapestry of anthemic themes

Anthems often combine multiple themes. For instance, here is a thought: let us rob Peter to pay Paul, but take no cut. With no cut there is no direct gain, so this is not an anthem of victory.

But we are still punishing Peter—not by robbing him, which would be wrong, but by imposing a fine that he owes for some misdeed. We are still bestowing largesse on Paul—not as an undeserved windfall, but a repayment of some debt he is rightfully owed.

We cannot literally say, or even think, that we are getting our rocks off by hurting Peter, and feeling big by patronizing Paul. But if we find a history that narrates Paul’s injustice and Peter’s crime, we will find it beautiful. This is history that matters!

This is how thymos, ambition, contaminates logos, reason, letting a truth market select for and evolve mere pretty lies.

Vanity, empathy, and mimesis

Still using the same example, let’s take an even deeper dive into the psychology of an anthem.

Neither the creator of the above history nor its consumers think (unless they are that rare sociopath) that the goal of the act it proposes is to gain power over both Peter and Paul.

This intention is the farthest possible thing from their minds, which are not operating on a Machiavellian level at all. If normal people, they are quite sincere in their literal voices.

Of course, they sense some passion amidst their reason. Of course, they attribute this tingle to a different emotion: agape, meaning charity or empathy.

Unlike thymos, agape should not contaminate logos, because it is altruistic to implement altruism logically. This is a nice theory—leading to the world of “effective altruism”—but, of course, vanity has nothing to do with empathy.

Agape contra thymos

The power of thymos to mimic agape makes it easy to see how both sides think they’re about to fight the zombie war.

Other humans who fail to respond to the songs of empathy that move all normal hearts must be cold, inhuman, even evil. Zombies must be fought with the cold fury of zombies. Thus both sides see themselves as humans against zombies.

But how can we tell the difference? Agape is real. But it works by different rules.

The natural instinct of social empathy is never uniform. It always declines with social distance. It is therefore clannish, tribal, and nationalist. In ancestral humans it tends to decline past zero to antipathy, often homicidal, by the nearest natural border.

For a million years the young men would kill male strangers on sight, as chimps do. Ours is an absolutely awful genus. This natural social instinct can be harnessed in civilized governance; it cannot be ignored; it should definitely not be used “as is.”

That truly uniform human agape, not clannish or tribal or nationalist, can be defined we do not doubt. Uniform empathy is certainly not the emotion of a chimp. It is the emotion of an angel, or at least a saint.

Saints exist. Anyone can design a constitution for them. All must quail before the zeal of any constitutional engineer who declines to design a machine for the sinful customers as they are, instead designing one for the nation of saints that after their imminent spiritual revolution they must become.

So we are doubly justified in suspecting that most purported empathy contains at least some dose of ambition. Most wasabi is dyed horseradish. Most people who taste real wasabi prefer the horseradish.

True empathy has its charms; it makes dubious political mortar. Ambition is just a better building material. Not only is it much cheaper, it’s usually more attractive.

Thymos, shameless as any desire, is happy to burrow into either form of empathy, instinctive or saintly. Instinctive empathy is naturally beautiful; saintly empathy is supernaturally beautiful. Since thymos too is beautiful, either makes an excellent disguise.

One way to test purported empathy for deeper ambition is to check its response to disappointing results. True empathy is logical; however much it cares, it only cares about results. Persistently ineffective or counterproductive charity often conceals ambition.

We can find pairs of comparably empathic histories, only one of which is an anthem. If the anthem is much more successful, the market for histories is probably selecting for ambition.

Consider two histories of climate change. One suggests that the best approach to the issue is restricting consumption. Another suggests some technical response: nuclear power, geoengineering, or carbon capture. Since restriction is coercion is punishment, it is an anthem. Geoengineering, or whatever, is not.

Assuming both options are equally sensible in reality (surely a baseless assumption), we would expect the anthem to be much more popular in the marketplace of ideas. And indeed it is.

Pistos: the desire to follow power

Late in the 19th century, Gaetano Mosca coined his concept of the political formula. A political formula is a story that serves the regime. The more people think it, the stronger the regime. To put it differently: a formula must be objectively loyal.

Political is a shifty word; what Mosca meant was sovereign. And not all powers are sovereign; nor is sovereignty implied in pistos, the Greek word for loyalty to any master. So a more general case of the phenomenon would be a pistoic formula.

This generalization gives us a way to move the problem outside the tricky area of sovereign power, and into the better-known territory of corporate power.

If a political formula is propaganda, a corporate formula is marketing—or, worse, internal cultiness, like a Japanese zaibatsu’s company song. Hollywood has taught every Western adult how to understand and defuse creepy corporate propaganda.

Suppose you read about a new piece of research which suggests that climate change isn’t that bad at all. It might even be good! These researchers have the best possible credentials: Harvard all the way, yadda yadda.

The good news was about to make your whole day. Then you looked more closely. These “scientists” were actually funded by Exxon. Oops, sorry for forwarding that. Clearly, as they say in Italian football, è pagato. Well—anyone can turn to the dark side.

How loyalty really works

Actually you are wrong about this—but also still right. Exxon has class. No one with class would ever just pay a scientist for useful results. No scientist with class would ever sell them. Yet your basic perception remains basically correct.

Loyalty is an emotion, not a reason. “I pay my taxes because the police will come to my house” is not a political formula, because it is not an aesthetic or emotional bond. “I pay my taxes because the money supports good works” is a political formula. (Which does not prove it false.)

The scientists funded by Exxon are loyal to Exxon. This is not a business transaction; it is an emotional attachment. Largesse is not a loan. Loyalty is not a debt.

Even if these scientists are as capable and honest as any saint, their aesthetic judgment is tilted. It is inevitable that they will perceive data which supports their patrons’ interests as clear and representative, and data which opposes these interests as noisy and misleading.

They may only pursue hypotheses favorable to their patron. They may only report data which supports their hypotheses. In these or a thousand other unconscious ways, these scientists will tend to generate only papers which are corporate formulas for Exxon.

The sensible response is not to debug their work, just ignore it. Science should not have a conflict of interest. (Exxon, in real life, has long since recognized the futility of this effort.) We can just say: never trust content from ExxonMobil.

Okay: get ready for a little discomfort.

How sovereign loyalty really works

Other scientists of the same caliber are actually working on the same problem. Their funding comes not from Exxon, but NOAA. It is not corporate, but sovereign.

Well, that’s all right! But—wait: Where the interests of NOAA are concerned, the relevance of climate change is, if anything, more apparent. NOAA has a budget process. This research is at least as relevant to NOAA’s cashflow as to Exxon’s.

What if the scientists are loyal to—NOAA? Or—USG itself? Yet nobody says: never trust content from NOAA. Hm.

Whom else would you trust? Who studies climate science, yet is not professionally loyal to institutions that will grow larger and stronger if the public worries more about climate change? Nobody, more or less. Hm.

If we apply the same standard of conflict as with Exxon, we exclude all the real experts as well. Whether or not they are on staff at NOAA and other agencies, their grants are from there.

So we have no trustworthy information at all, unless we choose to tolerate this obvious conflict of interest, for some improvised reason (elections?) that seems remote, mystical, and perfunctory.

If we have one book of epistemic rules for Exxon and another for NOAA/USG, we have dug a deep philosophical hole. Climbing out will take a great explanation of why what looks exactly like special pleading, driven by emotional loyalty to power, isn’t.

If we use the NOAA rules for everyone, any flack with Excel and a budget can con us out of anything. And if we use the Exxon rules for everyone, we know nothing at all about climate science—and some other fields.

This question is not confined to NOAA.

Assessment of compromised fields and methods

A field of expert discourse is vulnerable to these aesthetic tilts if propositions in that field have implications in the real, political world. It is easier to list the invulnerable fields—there are fewer.

Unaffected thought will be found wherever no valid thought is anthem or formula. The institution of mathematics can be politicized. The math itself cannot. There is no such thing as a (politically) ambitious or loyal proof. The same is true of astronomy, botany, chemistry, and many other pure and boring sciences.

In our old friend the totalitarian platypus, the same fields tended to be immune—with occasional bizarre exceptions that prove the rule, like Lysenko’s biology or “German physics.” When we look at the entire Soviet academy, we see that Soviet math, Soviet physics, Soviet chemistry, etc., is just science—maybe with slightly lower critical standards.

But Soviet history, etc., is thoroughly contaminated and generally worthless. This is because history has political implications and math does not.

While all the details are different, we now see in principle how this entirely decentralized and spontaneous order—an invisible hand not benign but malignant: an invisible fist—can distort the public perception of reality no less effectively than the visible fist of a classic centralized despotism.

If we generalize across man and platypus, democracy and dictatorship, we see power in its full complexity. Power is a magnet; it bends truth both ways; it can both attract and repel. It can push the filings around; it can also pull them in.

One regime bans newspapers it doesn’t like; another subsidizes newspapers it does like. One represses thought; another seduces thought. The former is uglier; the latter, more deceptive. The outcome is the same: every thought that can serve power does.

TLDR: we actually know nothing about anything, except math and super-hard science. Very cool.

Assessment of compromised markets and minds

The climate change hypothesis is a winner in two separate information markets: the market for scientific consensus and the market for public opinion. These different markets have different interpretations of loyalty.

Within the academy, the presumed loyalty is to science as an institution—whose interests need not be perfectly aligned with those of science as a mission.

Across the public, the presumed loyalty is to the regime—to power as a whole. Of course, scientists are also citizens, and this tilt can also affect them. Thus the anthemic and punitive nature of global decarbonization is peculiarly attractive.

Power is muscle. Rest softens it; action hardens it. Power is only as strong as its last act. Power loves to act! Therefore it loves any reason to act.

The story of climate change is such a reason on the grandest scale. Those loyal to power will see it as a loyal and therefore beautiful story, tilting their aesthetic sensors and potentially distorting their critical judgment.

Here we see just how blissful the union of thymos and pistos can be. Ambition and loyalty may contrast; they do not conflict; the contrary—they fit together like burger and bun. Most anthems serve power; most formulas imply status.

An anthem is a way to feel important. A formula is a way to support the government. Therefore, a formulaic anthem is a way to feel important by supporting the government.

Moreover, let’s remember our focus on informed elite opinion, not popular educated opinion. By definition, both the need for status and power, and any contribution to actual political decisions, are hallmarks of the gentry, nobility, or governing class.

Therefore we can say: an anthem is a way for the ruling class to feel important by supporting the government.

Political instinct, from biology to history

So far we have focused on individual emotions. All collective thought and action is made out of individuals; no society has any magical extracorporeal gestalt. Yet humans are a crowd species; our groups, like any sparrow-flock, seem almost individual.

Human hunter-gatherers and wild chimpanzees share more or less the same social structure, which must be five million years old and could be ten: the tribe. Surely our political instincts worked out well for us in this evolutionary environment.

Why are we emotionally attracted to ambition and loyalty? Why are both so beautiful that they can confuse our sense of truth? Because a taste for both arts is as critical to reproductive success for an Elizabethan courtier, as for a Kasekela chimp.

And if, while these tribal instincts sort of still worked in the modern world, in other ways they really kind of didn’t? This would be so consistent with many of our little biological woes. Is our taste for politics so different from our taste for sugar?

Instinct is not intelligence. No hardcoded program is perfect. But in a stable adaptive environment, an instinct that fails systematically will have long since been revised by evolution.

In the tribal world, not only were political instincts like loyalty and ambition productive for us individually—they also tended to work out well collectively for the tribe.

Biologists still argue about group selection, but a dysfunctional tribe is unlikely to pass on any DNA. Massacre has always been a thing. While you’re bickering endlessly around the cave fire, the next tribe over is figuring out how to just eat you.

In modern civilization, these equations need not hold. Any of our instincts may be dangerous individually or collectively. Evolution just hasn’t had enough time yet to tune our biology.

From individual emotion to collective intent

Many if not most political stories, whether or not they qualify as anthems or formulas, qualify as collective intentions: plans or agendas for collective action. Even many pure descriptions are fashioned around some implicit intention.

In English, intentional language often uses either the passive future imperative (what “should be” done), or the collective first-person plural imperative (what “we should” do, oddly like the old “royal we”).

Intentions are subject to an interesting comparative analysis. Every intention implies some real-world goal. The intention is also a thought, competing in the market for thoughts. If this thought prospers, its popularity may affect objective reality.

When we compare the explicit purpose of some intention to the expected impact of its popularity, we are comparing apples to apples. This fruitful analysis reveals three classes of intention, which we’ll call Machiavellian, para-Machiavellian, and pseudo-Machiavellian:

A Machiavellian intention has an impact matching its purpose. The purpose may not be good; it does what it says on the box.

A para-Machiavellian intention has an impact not matching its purpose. These ideas can be quite dangerous. (Many, of course, are mostly harmless; some are even beneficial.)

A pseudo-Machiavellian intention has no impact: it is thymotic pornography. It engages political instincts without changing the real world—like being a sports fan.

In the adaptive evolutionary environment, it seems likely that our political instincts had much more effective Machiavellian outcomes. We need to learn to manage these instincts in the modern world—or else change the world to fit around them.

Collective impacts of political formulas

This classification gives us a clearer handle on the political formula. The definition of a formula, relative to any power, is objective: its popularity advances the interests of that power.

The simplest form of political formula is purely Machiavellian, like the SS motto of “our honor is loyalty” or the Leninist “sacrifice everything for the Party.” This militaristic form of loyalty is somewhat de trop in our gentler, more ironic age.

Intentional loyalty (trying to help the Party), emotional loyalty (believing in the Party), and objective loyalty (being useful to the Party) are three different things. One of Orwell’s grim truths is how easy it is to be objectively useful to a regime by intentionally rebelling against it.

More subtle and more common than the purely Machiavellian formula is the para-Machiavellian formula—emotionally loyal, objectively loyal, not intentionally loyal. Strengthening the regime is an unintended consequence of this intention’s popularity. But this consequence remains welcome. It may be obvious, in which case it is still beautiful.

A common intention of this form is an agenda whose ostensible goal, good or bad, cannot be achieved without also punishing the political enemies of the regime. If this unintended consequence is seldom advertised but still easy to see, the agenda will still succeed as both anthem and formula in any truth market. “Winking at the market” is a time-honored Wall Street strategy.

Pervasive error and distributed despotism

Any despotism is the tyranny of error. No one sensible could possibly mind a benevolent dictator who was also always right.

Distributed systems are hard. It’s amazing when they work at all. We shouldn’t be surprised to see failure modes. But nor should we have to live with, or be ruled by, pervasive error.

So we should admit that distributed despotism is caused by the way power poisons truth markets. Putting a truth market in power is unsound political engineering. A previously reliable machine will start to evolve pretty lies. This is a slow and degenerative process which cannot be reversed.

Putting a church in charge of the government is not putting God in charge of the government. Putting a truth market in charge of the government is not putting truth in charge of the government.

Returning to our original comparison between centralized and distributed despotisms—dictatorship and democracy, platypus and man—it’s remarkable how these very different systems converge on the same “track-aligning” effect, repressing thoughts that challenge the regime, promoting ones that flatter it. Yet distributed evolution does often uncannily mimic central design.

Power is power. Through some pyramid of bureaucrats, the Central Committee ordered Havel’s greengrocer to display in his window their official slogan: “workers of the world, unite.” Do not our stores have such slogans in their windows? I see them every day; don’t you? They even come preprinted in all the right colors.

Yet our slogans are not so standard, nor our cadre so pyramidal. This is no flaw of power, but its dazzling perfection. The entire system, whose objective strength we just compared to the Czech secret police, formally does not exist at all. Very cool.

A theory of wokeness

Wait. Wasn’t this chapter supposed to be some kind of attack on progressivism?

Yes, and it is. We just went the long way around. There are fewer minefields on the deductive side of the hill. If you didn’t read this essay as a theory of wokeness, read it again.

Nor is this an attack; just an explanation. Similar theories are not hard to find among various foes of progressivism. They are too often stated as indictments, implying systemic mens rea. This deep factual error is deeply enfeebling.

The most sympathetic explanation is objectively the strongest, most convincing argument. My own personal sympathy is only philosophical: not emotion, just principle. Every writer harbors both eros and thymos; both should keep off the page. I, too, dislike progressives. But they are normal people, not evil zombies.

And for all its flaws, our marketplace of ideas might still learn that progressivism is a way for the ruling class to feel important by supporting the government.

A microhistory of media evolution

Finding the anthems and formulas in progressive ideas is an excellent critical exercise for the curious. Eventually it gets easy and repetitive, but it can be challenging at first.

And a good theory should always be solving more mysteries. The explosion of progressivism in the early ‘10s is coincident with the rise of social media. The two are probably connected. How? It’s a good excuse to trace the evolution of woke.

The story starts with two concurrent trends: the shift from site-based to social discovery, and the rise of new-media sites that connected analytics directly to their editorial process.

While these changes did not increase the competitive advantage of woke anthems in the news, they vastly increased the evolutionary efficiency of the market. The inscrutable algorithms instantly sensed the latent power of wokeness, and amplified it; and as it was amplified, it excited further market demand. The evolution of ideas, once a lazy ripple of views and reviews, had become an instant viral loop. Darwin started grinding up his Adderall.

It is still not easy to predict the future of the progressive century. It did not start in 2012. It will not end by 2022. It may not end by 2102. History, always contingent, is full of endless dry stalemates and sudden, sickening turns. Yet it never hurts us to learn more of its causes and its patterns.

The long cycle of truth, power and error

We end (for now) with a paradox on a long horizon. Consider this cycle:

- The intellectual command economy rules. Public opinion is directed by a dogmatic bureaucracy, rife with pervasive error, systematically incapable of changing its mind.

- An unofficial free market for truth evolves. This market cannot be poisoned by power, because it has no power. It develops a higher-quality product than the official narrative.

- A new epistemic elite arises. The old intellectual bureaucracy, smart enough to sense its own inferiority, hands power to the new truth market. A new golden age begins.

- Dogmatic bureaucracy returns. Slowly and inevitably poisoned by power, the once-vibrant civil society slowly ossifies into a dogmatic bureaucracy, evolving more and more pretty lies until pervasive error is again the norm.

Western civilization has been repeating this story over and over for roughly the last half-millennium. At each step in the cycle, there is no clear way to prevent the next.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Romanticizing direct democracy leads to pandemic anarchy.

We’re the ones to decide on whom we should rely.

In real life, trade-offs abound.

Leo Strauss and Russian Heideggerianism.

What I saw at the American Academy of Religion.