America’s ideals are worth defending against two-bit impostors.

Springtime for Mercenaries

The 50th anniversary of a classic adventure novel provokes reflection on a romantic yet gritty aspect of modern warfare.

Fifty years ago this June, thriller writer and former journalist Frederick Forsyth released his third novel, The Dogs of War, about a coup carried out by white mercenaries in a small imaginary African country, Zangaro, where a mining company has discovered a mountain of platinum. Like his earlier books Day of the Jackal and The Odessa File, The Dogs of War was a bestseller. Critics praised it for its attention to detail, almost as if it was a manual to carry out such an operation. The New York Times, however, mocked it for “a kind of post-imperial condescension toward the black man,” where five Europeans and six natives “are enough to deal with the mad dictator’s palace guard of 40 to 60 elite troops and a back-up army of 400 men.”

Thirty years later, secret UK government documents revealed that Forsyth’s novel was in fact based on a true-life effort by a small group of Europeans (including, probably, Forsyth himself) and Africans to overthrow the real-life regime in the very real country of Equatorial Guinea, a tiny (at the time, poverty stricken) former Spanish colony in the Gulf of Guinea. This was a country ruled by an all-too-true “mad dictator” at the time, Macias Nguema, democratically elected but a psychopath, a cannibal, and a communist. Forsyth had spent time in what was then called “the Dachau of Africa” while covering the Biafra War raging nearby in Southern Nigeria.

Forsyth’s book is probably the War and Peace of African mercenary fiction, certainly the only bestseller in the genre to date. The category began in the sixties, with Jean Larteguy’s 1963 Les chimères noires and Wilbur Smith’s 1965 Dark of the Sun as early examples. Both of those books inspired by the white mercenaries, Europeans and South Africans mostly, who fought in the Congo Crisis for most of that bloody decade. Irishman “Mad Mike” Hoare, the Belgian Jean “Black Jack” Schramme, and the Frenchman Robert-Pierre Denard were real-life adventurers, seemingly larger than life although the reality on the ground was often rather sordid. These were less free spirited “Wild Geese” than contract employees of mining companies or agents of French Intelligence and other shadowy players. Notorious or romanticized in the West, these were also les affreux, “the frightful ones.”

Hoare and Denard were probably the most famous, but there were hundreds of them. Major “Taffy” Williams fought in the Congo (Katanga) and later was a prominent commander for the Biafrans in their bloody rebellion against the Nigerian government. Forsyth knew Williams and he is probably the model for Carlo Alfred Thomas “Cat” Shannon, the mercenary hero of Dogs of War. Then there were the Germans, Rolf Steiner, who served in the French Foreign Legion, in Vietnam and Algeria, and then in Biafra and South Sudan. And Siegfried “Congo” Müller, an Iron Cross First Class-wearing veteran of the Wehrmacht who had fought on the Eastern Front during the Second World War and then in Africa.

Real or fictionalized versions of these characters are to be found on film, from the 1966 documentary Africa Addio to Hollywood’s Blood Diamond (2006). In terms of sheer production, the seventies was probably the heyday of mercenary genre writing, with the magazine Soldier of Fortune starting in 1975 and the publishing of paperback mercenary adventures like Frank Harvey’s The White Mercenaries (1972) and Frisco Hitt’s A Coffin Full of Dreams (1975). More polished, “literary” versions of the genre are to be found in the works of former U.S. diplomat W.T. Tyler (real name Samuel J. Hamrick), The Ants of God and Rogue’s March and Vietnam vet Philip Caputo’s superb 1980 novel Horn of Africa.

Not only was Frederick Forsyth’s mercenary opus not far-fetched, it inspired yet another attempt to overthrow the government of Equatorial Guinea, in 2004. The country had changed much in thirty years. It was now an oil-rich state, the third largest oil producer in Sub-Saharan Africa, and ruled by a much more stable and capable government (Macias Nguema having been overthrown and killed in 1979), but still small enough to be a juicy target. The 2004 plot, as documented in Adam Robert’s wild non-fiction book The Wonga Coup, was as extravagant and odd as past African adventures, this one involving Margaret Thatcher’s son, South African mercenaries, shady foreign moneymen, and several Western governments.

The two mercenary plots to overthrow the government of Equatorial Guinea, in 1973 and 2004, didn’t even get into the country. Both operations were frustrated by others before the bulk of the invading force reached the capital at Malabo. But the mercenary temptation to take over a small African state seemed to have been irresistible. In 1981, Mad Mike Hoare participated in a plot, backed by South Africa and some Kenyan politicians, to overthrow the leftist regime in the Seychelles. Hoare and his 53 men actually made it into the country before the plan unraveled.

The great African mercenary success story would be Bob Denard. A Polish comrade in the Congo described Denard as “a swashbuckler…who understood well the need to immerse himself in combat, in adventure, in risk.” No commander had a role in so many conflicts as the “Corsair of the Republic.” Writer Philippe Hugounenc lists Katanga, Yemen, Congo, Angola, Biafra, Kurdistan, Libya, Benin, Chad, and the Comoros. Many of those were stillborn, failed attempts. But it was in the Comoros, another small island state like the Seychelles, or the offshore parts of Equatorial Guinea, that Denard, with 46 men, succeeded in overthrowing the local government in 1978 and ruling the country behind the scenes for eleven years. And it would be his former patrons, the French government, who would force “the last of the pirates” out. Denard almost succeeded in taking over the country again, in 1995, only to be frustrated by French Marines. It would be the last of his four coup attempts in the Comoros.

One would think that, as the old war dogs turned gray, that the age of the mercenaries was passing. The South Africans created Executive Outcomes, a private military company, in 1989 and it provided expertise and guns for hire in brush wars in Angola and Sierra Leone before it was dissolved in 1998. This would increasingly be the model for the future, instead of hiring individuals, governments would now hire companies for their wars. In 2020, The Economist described the continued hiring of mercenaries by African regimes as “cheap, efficient and deniable.”

Mercenaries are, of course, nothing new. Wars tend to beguile adventurers and some of them are going to be foreigners attracted to the possibility of financial reward, if not ideology. Iraq and Afghanistan had plenty of guns for hire, providing technical services or working as protective security details. In my time in Iraq, I recall seeing Americans, South Africans, Chileans, and Nepalese (Gurkhas) serving in such capacities. According to the Russians, there are over three thousand foreign mercenaries serving with the Ukrainians, with particularly large contingents from the United States, France, and Canada. On the Russian side in the Ukraine War, we’ve seen evidence of African, Syrian, and Cuban mercenaries.

And while the white mercenaries of Africa are legendary, or notorious, the case should be made that they were outnumbered by African and other mercenaries. Rwandan soldiers on missions in the Congo and Central African Republic essentially behaved as rapacious mercenaries, looking to benefit financially from the conflict. And there were few supporters of African and Arab mercenaries, of men with guns for hire, as assiduous as the late Libyan dictator Muammar al-Qaddafi. The consequences of Qaddafi-funded mercenary forces such as the Islamic Legion and the Volcano Army would reverberate for decades, helping to stoke the genocidal war in Sudan’s Darfur region.

If the Golden Age of African mercenaries was the sixties, we may be entering its Silver Age now. The impetus came from Russia, a seemingly unlikely source. Russia, meaning the former Soviet Union, never left Africa after the Cold War. I remember coming across Armenian pilots flying aging Soviet transports and Ukrainian mechanics servicing former Soviet patrol boats in African hinterlands. But the Wagner private military company (PMC) emerged from the fighting in Ukraine’s Donbas region a decade ago and only a few years later it was already operating throughout Africa. It was a PMC with obvious, deep Russian government ties, but that was nothing new. Many of the older generation of “Western” mercenaries had opaque ties with foreign governments, particularly France and South Africa. In the Congo, the Western mercenaries even worked with Cuban exile mercenary pilots funded by the CIA. Wagner’s appearance in Africa was not so much a break with the past, but rather a continuation of nefarious activities seen before. The Russians were imitating the very West they were seeking to supplant.

Wagner worked in many African countries but the bulk of Western attention, and recent Western hysteria, about Russians in Africa has become a cottage industry, focused mostly on four countries: Libya, Sudan, Mali, and the Central African Republic.

In Libya, the Wagner Group entered supporting one faction against another in a fratricidal civil war. The Russians were on the same side as the Egyptians and Emiratis and opposed by the Turks and Qataris. Both sides had contending Syrian mercenaries, veterans of that country’s civil, in their ranks.

In Sudan, the Russians were invited in by the Bashir regime and the military/commercial relationship continued after Bashir was overthrown in 2019. Wagner went into the billion-dollar goldmining and smuggling business with Janjaweed warlord Muhammad Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti. When war broke out in April 2023 between Hemedti’s forces and his rivals and former partners in the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), both Americans and SAF supporters sought to highlight the Wagner connection as a way of giving some sort of geostrategic importance to a conflict (and humanitarian disaster) that the West has largely ignored. Wagner’s Sudanese operations were at some point overseen by legendary Wagner commander Aleksandr Kuznetsov “Ratibor,” a former GRU commando who fought in Syria and Libya (where he was severely wounded) and later, in Ukraine. Like Libya, Sudan’s problems are, of course, mostly of its own making and the Wagner presence, corrupt as it is, was only a sideshow in a much larger and older internal conflict.

Russia’s presence in Mali is not only notorious because of substantive claims of human rights abuses but because the Russians displaced France and, by extension, the United States. A May 2021 military coup in Bamako led to a French decision to withdraw their Operation Barkhane troops fighting Jihadists. Mali’s generals turned to Wagner and the Russians as substitutes in late 2021. Throughout the Francophone Sahel, the Russians have exploited and benefited from long-existing tensions between local regimes and the former colonial power. But as in other African conflicts, these were not situations that originated with the Russians, who saw an opportunity and took it.

Wagner’s mercenaries in Africa—like their Western predecessors in the sixties—have failed at least as often as they have succeeded. Their most successful intervention has been in the Central African Republic, one of the most conflict-ridden countries on the continent. The Texas-size CAR, with a population of only six million souls, is resource-rich but historically impoverished, and was one of the African states most dominated by French neo-colonialism in the years after independence, with French troops as a near permanent presence and Paris making and breaking local presidents (and one emperor). There is almost nothing the Russians have done in CAR that the French didn’t do first.

The country had already been in strife for more than twenty years before the Wagner Group arrived. Wagner’s arrival in 2017 was a desperation move by the country’s president Faustin-Archange Touadéra to replace departing French troops and incompetent U.N. peacekeepers. The Russian intervention, brutal as it seems to have been, succeeded in the sense that it extended the sway of the central government over more of the country and secured a tenuous stability. In return the Russians worked to secure valuable natural resources for their own benefit. This is an old African story of cynical transactional politics, riches, and resources in return for brute force and firepower.

After the Wagner Group’s failed 2023 revolt against the Russian state, the Americans saw an opportunity to try to replace the Russians in CAR, to do to the Russians what the Russians had done to the French. In late 2023, an American “private security” company named Bancroft Global Development with years of experience as a US government contractor, especially in Somalia, offered to provide an alternative to the Russians in Bangui. According to several news reports, a key figure in this seemingly failed American gambit was one Richard Rouget, once an associate of Bob Denard, “last of the pirates” and the Congo mercenary who became de facto ruler of his own African state. Rouget was reportedly even part of Denard’s presidential guard on the Comoros. As Forsyth wrote, “in war, there are no winners, only survivors.” After 50 years and numerous cycles of geopolitics later, we are back to the world of the Dogs of War.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

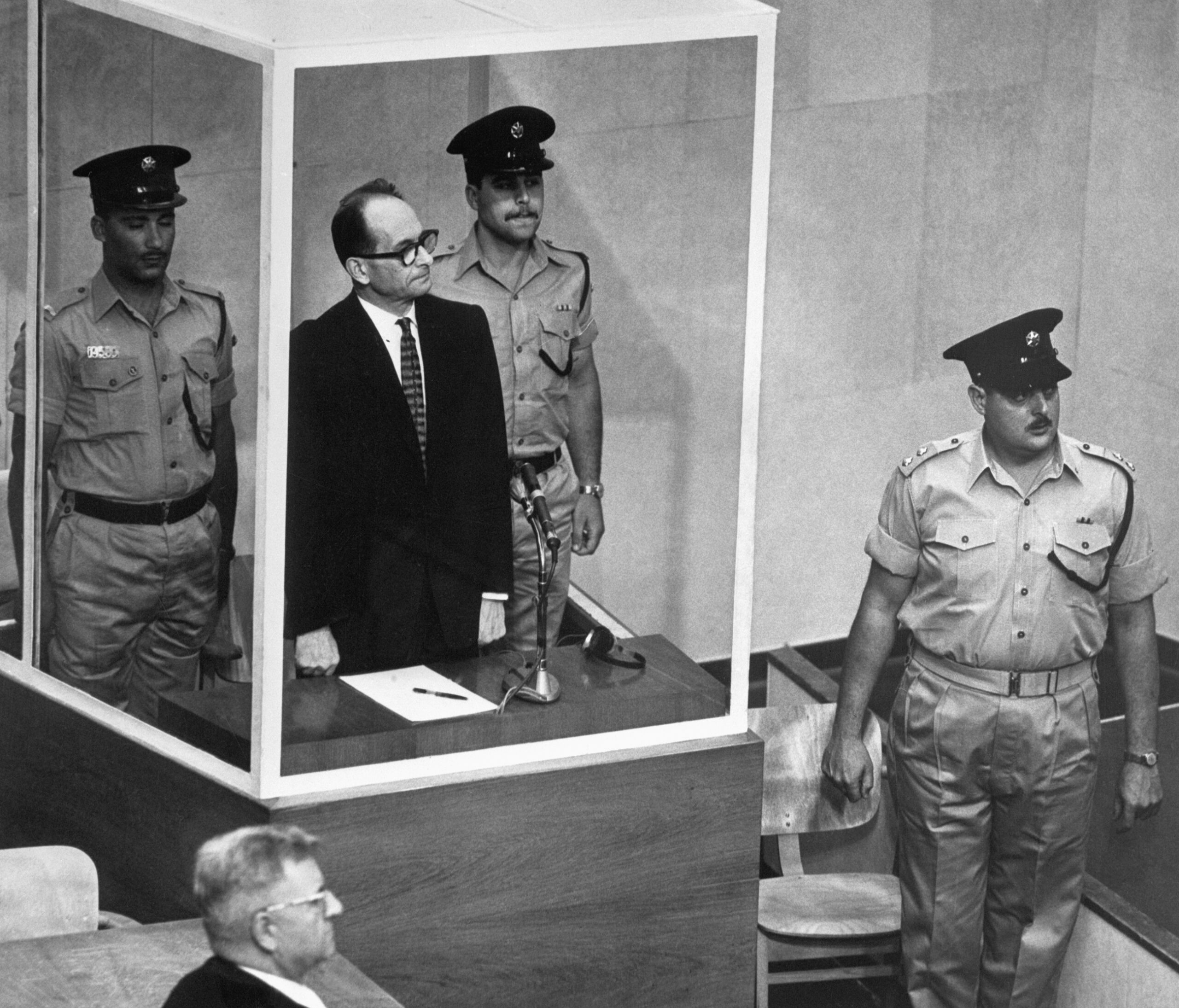

Destruction and violence are anything but banal.

With a recruiting shortfall of 25%, the U.S. Army’s total force will be undermanned by 15,000 soldiers. Leadership needs to be held accountable.