Are AI demons real?

The Allure of Evil

Destruction and violence are anything but banal.

If the Holocaust is the 20th century’s most infamous example of evil, then perhaps the most famous reflection on the nature of evil is Hannah Arendt’s contribution to Holocaust literature, Eichmann in Jerusalem. It is a work remembered above all for its striking and influential subtitle: A Study in the Banality of Evil. Fascinated by Nazi official Adolf Eichmann’s apparent lack of moral depth, amazed at his seeming inability to understand the wickedness of the Final Solution or the role he had played in pursuing it, Arendt concluded that Eichmann and the bureaucratized evil he represented were “banal.”

In the decades since Arendt’s work was published, the idea that evil is banal has become a virtual cliché. It has been reinforced by the steady stream of news about evil that appears in the press. Reports of shooting, murders, massacres, and war crimes are regular occurrences. Clothed in a certain routine familiarity, they come to look even more banal.

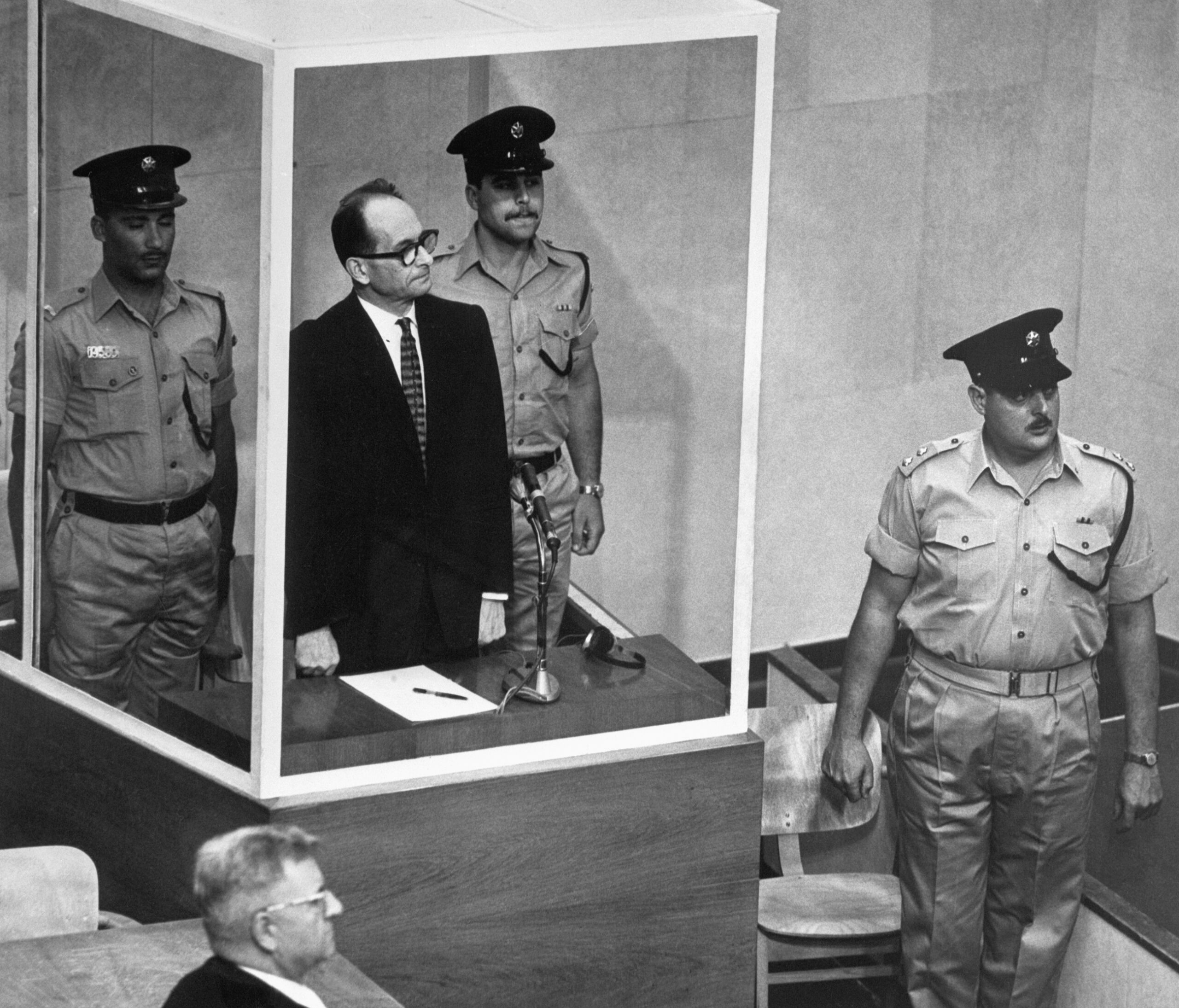

And yet there are very serious grounds for rejecting Arendt’s thesis—even in Eichmann’s own case. Subsequent research has revealed that he was very much active in Nazi circles as an emigrant in Argentina. He was fully committed to a ferocious anti-Semitism, well aware—and proud—of his own role in the Final Solution. The Eichmann on trial in the glass box in Jerusalem was an act, a character he was playing for the audience, and Arendt fell for it. He may not have been an intellectual, but he was no mere manager of railway timetables either. In short, he was anything but a case study in the banality of bureaucratic evil.

But even if we were to allow for the sake of argument that Eichmann himself was as banal as Arendt thought, it is surely implausible to see this as a key to understanding Nazi evil. How and why does a mediocrity become such a monster? And moving beyond Eichmann, we have to face that other problem of evil—not the typical question of its origin, meaning and significance, but rather that of its apparent appeal. Evil is often exhilarating and exciting. And one does not need to be evil to provide evidence of this. Serial killers are truly evil. But what of those who pore over books and flock to movies based around serial killer plotlines? They are not evil, but they are nonetheless fascinated by it. True banality—as represented in the lives that most of us lead most of the time—makes for neither good television nor bestselling pulp fiction.

A Beautiful Madness

And so if the foot soldiers of the Holocaust cannot be identified with mere banality, what might help to shed light on them? Surely part of the explanation has to lie with the aesthetics of evil. Take, for example, Leni Riefenstahl’s notorious film of the 1934 Nuremberg Rally. The opening sequence begins with a statement about Germany’s wartime humiliation and then her rebirth with the election of Hitler. This is followed by a view of the medieval German city taken from Hitler’s plane. Then there is the arrival of Hitler and the Nazi elite, greeted by adoring crowds as the Führer’s motorcade drives through the streets. Then there are the speeches, the torchlight parades, the scenes of joy, and, of course, the carefully choreographed marches of the rally itself, culminating in Hitler’s ascent to the rostrum. Countless images draw upon the mythical medieval glories of the German people, and the whole production speaks of the returning significance and power that the Third Reich represents. Everything is designed to stimulate a seductive desire in the audience to belong to something that gives meaning to life.

The power of the movie lies not in an argument so much as in a collage of sights and sounds designed to cultivate an aesthetic response. And when one considers Nazism more broadly—the uniforms, the titles, the evocation of German glories, past and future, the posters, the parades—it is clear that no compelling explanation of the practical and powerful evil of Nazism can be offered which places banality rather than aesthetics at its heart.

This observation is surely not restricted to Nazism. The same surely applies to Stalin’s Soviet Union and to Mao’s China. And closer to the American home, one can hardly speak of the Ku Klux Klan without picturing its hoods, its flaming crosses, its night-time gatherings—its narratives and its symbols.

Arendt’s banality thesis is really of very limited help here. And this is where Freud and his followers at least offer an explanation that might take us nearer to the truth. In his most well-known essay, Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud described civilization as the product of communal repression, formed by sublimating the dark and destructive impulses that characterize mankind’s deepest and most pleasurable desires. Beneath the surface of civilized life are drives toward sexual satisfaction and violence, those which typically characterized the Id or the subconscious. Such desires, Freud argued, are redirected to other pleasures such as sports, politics, and art. These pleasures were not as satisfying as giving unfettered expression to the deep, dark denizens of the Id, but they followed a similar logic and were generally good enough to keep the barking hounds of desire at bay. Anyone who has played a contact sport knows that hitting an opponent hard is fun, if not quite as satisfying as completely destroying him. Freud knew that human beings are not at root rational. We are creatures of desire.

Destruction Chic

Freud’s understanding of human psychology informed generation of thinkers wrestling with precisely that question that Arendt’s banality thesis ignores: Why were movements like Nazism and Fascism attractive? In The Mass Psychology of Fascism, the Freudian-inflected Marxist Wilhelm Reich identified the aesthetics of these movements with a kind of erotic desire. His basic thesis was that a sexually repressive society made such things attractive to its people with the unspoken promise that they would bring with them a sexual power and allure that the banal, non-descript citizen lacked in himself. The attraction of Nazism, then, was precisely its apparent guarantee of non-banality. It was the erotic power of the images that made them so attractive.

“Remark the cut of the German uniform in the Nazi time,” wrote Philip Rieff, the Freudian cultural analyst, in the early 21st century: “No more erotic uniform has ever been created.… All talk of the banality of evil in such magnitudes seems to me ridiculous in its dependence upon a taste for good and sensible taste. The taste in modern politics is for blood.” What Rieff notes here is the inability of an intellectual such as Arendt to understand the deep, irrational appeal of aesthetics in the matter of evil. It was not Eichmann’s banality that made him a Nazi. It was his desire—a desire to belong, a desire to be powerful, to be part of something that reveled in the power of human violence, a power that was both destructive and seductive. Indeed, a power that was seductive precisely because it was destructive.

Much has been made of the illogic inherent in the fervid new politics of sexual transgression and racial subjection. But those who try to argue transgender extremists or BLM fanatics out of their position with appeals to “facts and logic” may be missing the same insight that Arendt missed. The irrationality is part of the point: what we are up against is a generation transfixed by the allure of desire, the delight and satisfaction of destruction which lets loose the forces held in check by civilization. Any effort to respond in a persuasive manner must come with an appeal to the heart—one that offers to satisfy not only material needs but spiritual longings for beauty, for meaning, for devotion. Evil is not banal, so good cannot be either if it hopes to triumph. The answer to our broken politics is not an argument but a prayer—not a syllogism but a vision.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

The struggle against transgenderism is a spiritual struggle.

An evil culture takes on a life of its own.