From God bless America to mob damn America?

Seeing Color

Tasteless jokes are the stuff of life.

When I was a babe in arms, still learning the facts of the world, I once pointed at an unsuspecting fellow in our apartment building and said to my mother: “man! Have penis?”

Besides proving definitively that I have been both gay and politically regressive pretty much since birth, this episode tells you something about how a little kid’s mind works. There is a kind of unreflecting frankness that makes a toddler shout loudly to his mother in a public place about distinguishing features which adults agree not to discuss. “Look, mom! That man is fat!”

As you get older, certain differences become forbidden to observe and therefore, of course, objects of fixation. This is a major reason why kids tell jokes about race in the schoolyard. Don’t lie about this: whatever race you personally are, you snickered with your buddies over punchlines that would be absolutely mortifying to repeat in polite society, especially today.

Some of these jokes were legitimately uncouth. Others were merely absurdist or silly. That’s because the point of telling them was not, importantly, to express hostility toward one race or another. It was to say things that were unsayable. Things you still found kind of interesting, though you now knew it would get you in trouble to say so except in confidence.

And so we whispered vulgar nonsense to each other and giggled like the doofuses we were. We still do it—don’t lie about that, either. Among friends, whatever your race or sex, you enjoy a good racist or sexist joke. You can admit it. It’s OK.

Except we all now know that these private indulgences and amusements are potential objects of very public and merciless scrutiny. Gun rights advocate Kyle Kashuv learned this when his enemies dredged up old comments he had made to friends via text message. Despite Kashuv’s apology, his offer of admission to Harvard was rescinded. Alexi McCammond learned a similar lesson when she had to resign as editor-in-chief at Teen Vogue because of tweets she wrote as a teenager.

In the digital age everything, from the chat room comment to the public statement, is subject to the same unremitting criticism and judged against the full weight of history. No protest of ignorance or innocence is enough, no intentions are sufficiently pure, to excuse those who fall afoul of the rules. My comment to my mother as a child, the jokes you whispered to your pals in grade school—these sorts of naïve indiscretions are now the stuff of character assassination.

No Safe Place

Of course these standards are selectively applied. That is the point: our new tastemakers want us to feel that we never know which untoward remark, which careless slip of the tongue, could be our undoing. We are expected to obsess over certain differences between us (for the love of God, never dare say you “don’t see color”), while also studiously ignoring others (the scrappy action hero from that show you like is now a woman. This change is completely persuasive and remarking on it is hate speech). One is never quite sure which demographic facts are to be spoken of, when, and by whom.

As a consequence there are fewer and fewer contexts in which straight people can feel comfortable making fun of their gay buddies, or white and black friends can rib each other without circumspection. This generates far more racial tension and social unease than any off-color joke ever could. Certain classes of people are now surrounded by an impenetrable wall of sensitivity, whether they wish to be or not. If I cannot freely mock you, and you cannot freely mock me, then we cannot really be close to one another. It takes me forever just to convince new straight friends that they really don’t have to watch their words around me, that I will only be offended if they refrain from making gay jokes on my account.

Eventually, toddlers learn not to shout about people’s physical attributes in shopping malls. But there is a time and a place for everything. When you get to know someone and understand his sensibilities, you can make jokes to him in private that no gentleman would ever make in public. There is a word for knowing a man’s sensibilities, and joking with him in private, and being at ease with him about even indecorous topics. The word is friendship. And to saddle friendship, from the schoolyard on, with the full burden of ancestral guilt and prejudice gone by—that is a prescription for hostility more sincere than any we ever practiced on the playground.

True friends have an ease with one another that comes not from ignoring awkward quirks and differences, but being at peace with them—even finding them amusing or endearing. It is the ease with which a husband teases his wife about her bad driving, or a Mexican teases his white friend about being a wimp when it comes to spicy foods. Our current moral panic basically makes it impossible to include certain kinds of people in this good-natured, all-American camaraderie.

We are not going to get past this with more squeamishness, more verbal hedging, more “awareness” of every possible implication that may attend upon every possible utterance. We are going to get past it at the cigar lounge and the gym, while playing pick-up basketball or video games, in the ever rarer and more precious private spaces where the crushing logic of public recrimination does not weigh on us and we can be as frank as toddlers with each other again.

Ordinary Americans who do not have huge platforms or political clout, but who want to do something for the salvation of this republic we love and share, could not do better than to start by defending those private spaces at all costs. The more people you know who can take your insensitive jokes and give back as good as they get, the more places you can meet with those people in trust and fellowship, the more territory you have claimed for the spirit of freedom and candor which alone can rescue us from our paralyzing fear of one another. It will not be enough just to meet in private. But it’s a start.

Nature’s God

This weekend is Presidents’ Day weekend. One of the presidents we are celebrating is Abraham Lincoln, who is also—though you wouldn’t know it from the present state of things—one of two people whose birthday serves as the occasion for Black History Month. The other person is Frederick Douglass. The carpenter’s son and the escaped slave: two men for whom the obstacles to shared humanity were very real, indeed.

Though Lincoln and Douglass disagreed about plenty, they had in common their rise from penniless obscurity to national prominence. From this, and from the classics of Western literature they both cherished, they learned that there is something more essential to a human being than the circumstances of his birth, his natural aptitudes, and even his intelligence. Both Douglass and Lincoln believed, above all, that as human beings we are equal in the sight of God.

“In Christ there is no Jew or Greek, slave or free, male or female”: when St. Paul wrote those words, he did not mean that there were no differences between men and women, or that economic disparity did not exist. He meant that precisely because those differences between us are so obvious and enormous, it is cause for amazement that God loves every person with a love that surpasses measurement or distinction. It is only in the sight of God, and so in the last and most fundamental analysis, that we are equal at all.

That is the kind of equality that both Lincoln and Douglass believed in. In 1857, after the Supreme Court upheld slavery in Dred Scott, Lincoln compared himself to a poor black woman: “In some respects she certainly is not my equal; but in her natural right to eat the bread she earns with her own hands without asking leave of any one else, she is my equal, and the equal of all others.”

This same divine equality that made slavery “an abomination in the sight of God” for Douglass. That is why he looked for encouragement to “the Declaration of Independence, the great principles it contains, and the genius of American Institutions”—because there it was promised that “all men,” whatever the differences between them, “are created equal.”

The censors who watch over us want us to be afraid of talking about our differences, as if noticing or discussing them amounts to hatred. If there were no God, this might perhaps be true. And since the censors do not believe in God, they cannot see how we can be equal unless we are the same.

But we know better. For though the thoughts of man’s heart are evil continually, and though it is possible for us to twist the raw materials of reality into all manner of hatreds and abominations, still reality itself was created by the God whose love for each of us is as entire as and as boundless as his very self.

This God is not afraid of our differences, nor does he want us to be. Like all the rest of his creation, the profusion of different races—each of them eminently and delightfully goofy in its own way—is part of the hilarity of life, a sheer profusion of excess for us to wonder at and laugh about. To suppress this is to insult the abundance of the God who made us—every last one—in his living image.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Can the veterans of the old conservative wars come to a truce?

A quick and dirty guide to regime propaganda

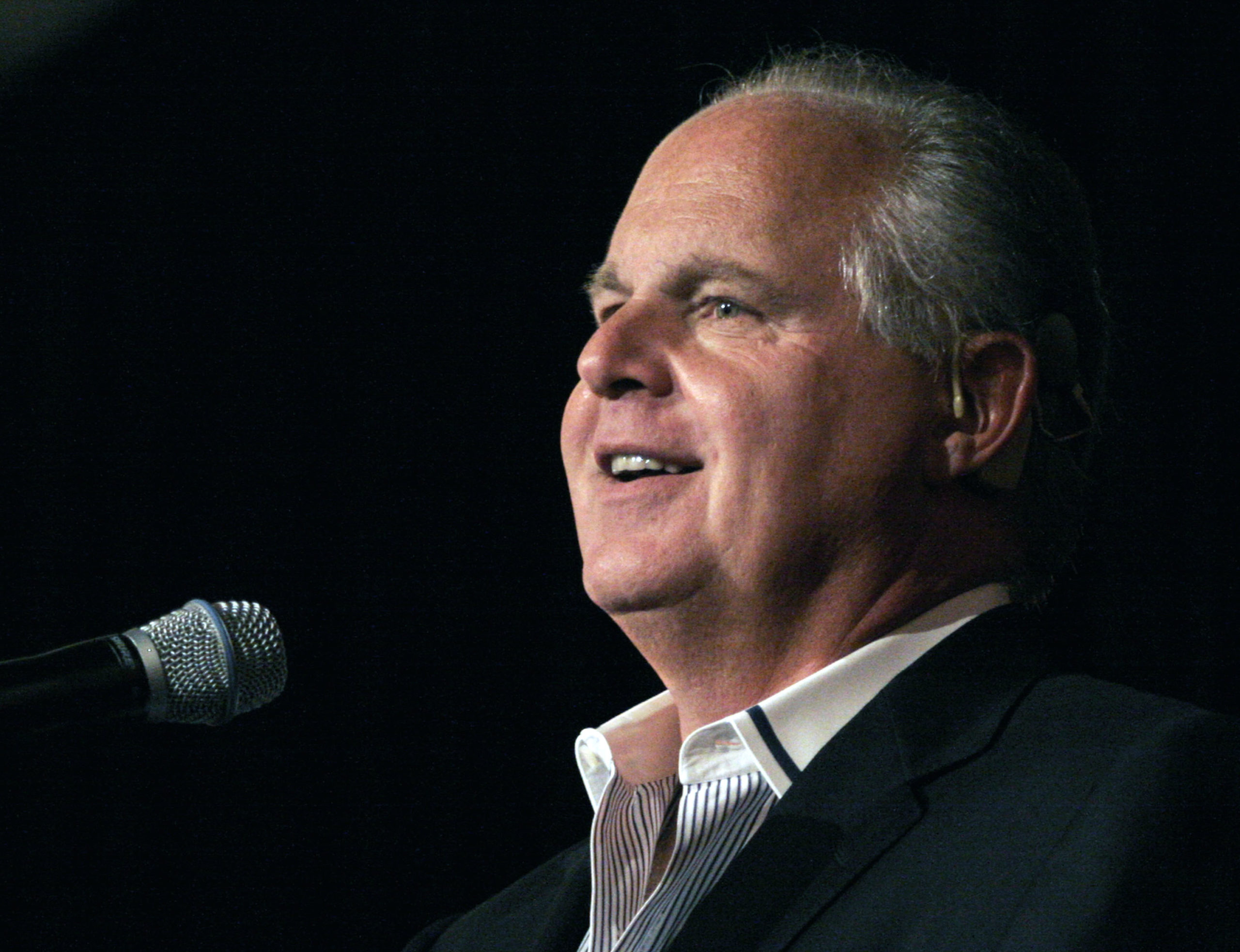

Rush Limbaugh’s on-air antics help expose the racist hypocrisy of today’s ideologues.