Manufacturing and experimenting on embryonic human beings is clearly unethical.

Science and Séances

Science may be science, but scientists will always be human beings.

“Follow the science” and “follow the experts” became popular maxims in America in the strange years 2020 and 2021 as government bureaucrats, politicians, media stars, and celebrities—themselves no scientists (or experts either)—struggled to figure out what, if anything, science and the experts wanted the rest of us to do. Following science and experts turns out to be a difficult and problematic enterprise.

Scientific American magazine has been around since 1845. Thanks to advances in science since then, you can get it digitally or you can still get your print edition delivered monthly. It presents itself as “the essential guide to the modern world,” offering “expert insights on the most . . . awe-inspiring advances in science by experts, including more than 150 Nobel Prize-winning scientists.” The title of the magazine and the time of its origin express an aspiration. Modern science was new. Darwin hadn’t yet published his On the Origin of Species. Einstein wouldn’t be born for another 30 years. People travelled on foot or horseback or in wagons drawn by horses or oxen. Steamboats were competing with the new railroads for trade and travel.

In the summer of 1924, an associate editor of Scientific American, the chairman of the Harvard University Psychology Department, an MIT physicist, and other scientifically-minded inquirers were frequent visitors to the four-story Boston town house at 10 Lime Street in the Beacon Hill neighborhood, a few blocks from the Boston Public Gardens. There, night after night, they attended séances conducted by Mina Crandon, the beautiful young wife of Harvard-educated surgeon Dr. Le Roi Goddard Crandon. Mina was popularly known as “Margery the Medium” or, more sensationally, as the “Blonde Witch of Lime Street.”

Mina’s local fame had been growing for over a year since she first revealed her mediumistic powers and started conducting private séances in her home. She had recently returned from a European trip, on which she had impressed eminent psychic investigators in London and Paris with her séances. In her trances, Mina could make tables move, Victrolas turn on and off, and bells ring. She could channel the voice of her deceased brother Walter, who would often recite limericks or make off color jokes. Now her eminent scientific visitors wanted to determine a scientific explanation for these supernatural effects.

They were members of a committee formed by Scientific American to judge a contest with cash prizes for anyone who could provide, under rigorous test conditions, a “psychic photograph” or an “objective psychic manifestation of physical character” in a séance. The committee had been testing mediums for a year and a half with no winners. Newspapers all over America were reporting what they called “The Great Spirit Hunt.” Now the Blonde Witch of Lime Street seemed on the verge of winning. An article appeared in Scientific American suggesting strongly that Margery seemed to be communicating with the dead. A headline in the New York Times read: “Margery passes all Psychic Tests!” With an exclamation point.

She would not win the contest. Months passed, and the committee issued a divided verdict. Unfortunately, at least one of the scientists on the committee could not resist the medium’s charms and had an affair with her; another was so deeply smitten with her that he wrote a 500-page vindication of her after the contest. Science may be science, but scientists will always be human beings.

To prove that government is the greatest of all reflections of human nature, a year after the Scientific American reached its verdict, Congress held hearings on a bill to prohibit fraudulent fortune telling in Washington, D.C. As one historian records, “It was public knowledge that Florence Harding, wife of President Warren G. Harding, regularly consulted a psychic who predicted her husband’s election victory as well as his unexpected death in office.” There was reason to suspect that such clairvoyant consultations were not confined to the executive branch. So Congress called expert witnesses to testify on the matter. The greatest expert on the subject was none other than the man who billed himself as The Great Houdini, “World Famous Author, Lecturer, and Acknowledged Head of Mystifiers.” The young Edmund Wilson, writing in the New Republic, opined that on “a committee of scientists of which Houdini is a member it is Houdini who is the scientist.”

Testifying at the hearings, Houdini displayed his scientific expertise on the floor of the House of Representatives. Demonstrating the best séance techniques, he proved that all the mediums’ claims of clairvoyance were pure fakery. He had even hired his own team of private investigators to investigate fraudulent mediums. His top medium investigator reported that Washington, D.C. was the “worst spot in the country” for fake mediums.

According to Houdini biographer Raymund Fitzsimons, when the hearings opened, the public gallery was crowded with “mediums, palm readers, astrologers, crystal gazers, and lucky charm sellers.” Many mediums testified that they were frequently consulted by senators and representatives and that the spirits they conjured had given advice on key legislation. They refused to give names, insisting on the right of privacy of the séance. But Houdini’s expert investigator named names. Chaos erupted: “The hearings . . . careened on for four raucous days. Order in the chamber disintegrated, police were repeatedly summoned, and the husband of a medium nearly punched Houdini in the face.”

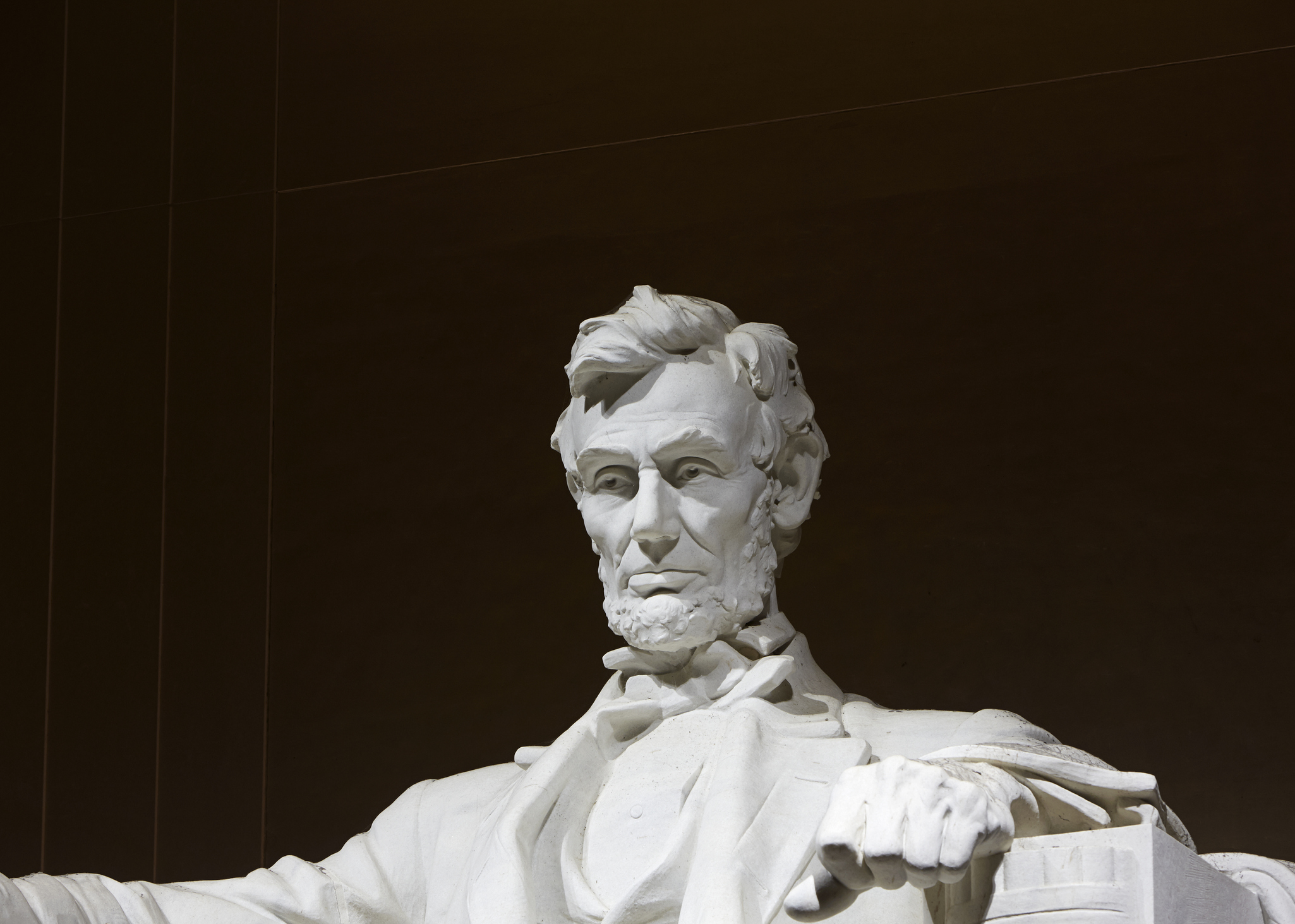

The bill didn’t pass on the technical ground that it would have been too difficult to enforce. But the scientific expertise of the Great Houdini, “Head of Mystifiers,” was more admired than ever. As proof of this, the Library of Congress possesses a photograph of Houdini with Abraham Lincoln’s spirit.

Sober observers, if any can be found, might recall the wisdom of America’s Founders that boldly rested all our political experiments on the capacity of mankind for reason and self-government but knew well that there never was and never would be a nation of philosophers—much less scientists.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

At what point does the Revolution swallow itself?

Wokeness is threatening our nation's historic sites.

We created a wasteland, and called it progress.

The greatest American film reminds us to give thanks that the cause of freedom remains there, waiting to be joined.

What's today really about?