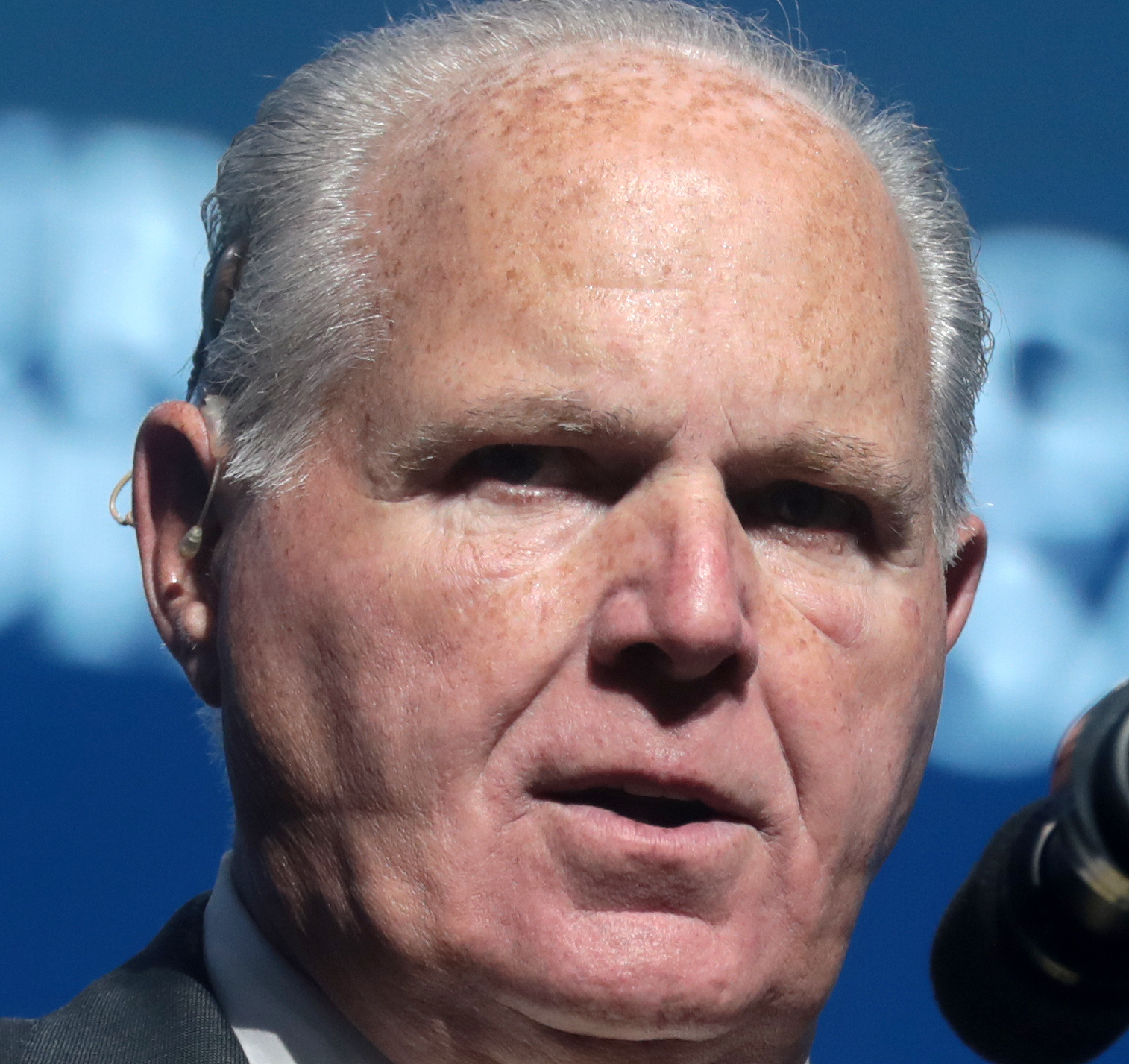

A patriot passes.

Rush Lives On

A threnody for my mentor.

There’s a long-running joke in the Limbaugh family about meeting someone new. When we introduce ourselves to someone using our full name, often the person will lean in to ask (as we brace ourselves for hostile comment), “Limbaugh? Wait, are you related to… Andy Limbaugh?!”

Andy, a guy who has never met a stranger, is a cousin of Rush Hudson Limbaugh III. And Andy’s story reveals an important aspect about how our family shaped Rush into a man who made Limbaugh a household name in all four corners of the world.

Born and reared in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, Rush was heir to a legal legacy of statewide repute, courtesy of his namesake and grandfather Rush Hudson Limbaugh Sr.—“Pop,” as we called him. Pop lived to age 104, and at one point past the century mark he was the oldest practicing attorney in the nation. Many remember radio Rush interviewing Pop on the show for his 100th birthday.

Being born into a legacy built on honesty, hard work, and especially education brings certain pressures to live up to the expectations of the public. When I was young, Rush and I formed a special bond over this very circumstance. My grandmother Anne, Rush’s aunt, often told the younger generations, “remember who you are and who you represent,” but as structure-averse natural pranksters, this reminder was often ignored.

You see, my gifts are musical, and it can be difficult for family, teachers, and peers to understand a career path that is not determined by good grades. Seeing a similarity to his own experience with school, Rush worked with my parents, a stockbroker and a judge, to allow me to drop out of high school and pursue music full time.

As Rush told me in a 2001 email shortly after he lost his hearing, “it would very unfortunate if anyone, no matter who (family) and what their best intentions might be, were able to talk you out of your current attitude. And there is no time frame you must meet. I didn’t become a “success” in most people’s eyes until I was 37 years old in Sacramento, doing my first-ever talk show. And even then, I earned “only” $45,000 a year. And EVEN THEN, because many in the family (and others outside the family) did not understand the social/business relevance and worth of being on the radio, I was still terribly worried about, as in,‘When is he going to outgrow this hobby and get serious with his life’s work?’” Rush never blamed his parents or grandparents, of course, but it was difficult for those generations—born on nineteenth-century farms and the first to attend college, their children members of the Greatest Generation—to understand that passion guided by wisdom is enough to make something of oneself.

It is a message Rush often repeated on the radio, but imagine being a kid and having the undisputed king of political entertainment tell you, “You can make it! Keep going! Do not listen to people who have failed.” It makes the heart glow with inspiration.

This brings me to the original joke: everyone in our family is someone living up to the Limbaugh legacy. Rush was proud of all of us. When my father Stephen N. Limbaugh Jr. received a federal judicial appointment, or years ago when cousin Dan was accepted into West Point, or his brother David hit the New York Times bestseller list, or other family members had major accomplishments, Rush always joked, “Congratulations! Finally, someone in the family is making something of themselves!”

Rush’s correspondence, like his radio show, was rife with humor. He once told a joke about a man who had gone to heaven. As Saint Peter escorted him through the pearly gates, they happen upon an unimaginably opulent throne room. Above the throne read the name “Rush Limbaugh.” “Wow, is this the room reserved for Rush when he comes here?” “No,” Peter replies. “This is God’s throne room, He just thinks He’s Rush Limbaugh.” When Rush met the Lord last month, I imagine God smiled and told him jokes like that are exactly why He gave him the gift of humor—to bring some levity to the nasty world of politics.

Rush’s humor came from his mother, known to me as Aunt Millie. (My grandfather, Stephen N. Limbaugh, Sr., shared a story about Rush flying her to New York to shop on Madison Avenue. After briefly perusing the fine women’s apparel, Aunt Millie turned to the clothier and asked if she could “take a look at the bargain rack.”) Equal to his humor was his generosity, which has fortunately been well-documented since his passing. The weeks leading up to Christmas were always somewhat difficult when the question of “what do we get Rush?” arose. Meanwhile, Rush himself would commandeer a room in his brother David’s house and stack up boxes on boxes of Apple products. One by one, we were invited in to pick out what we wanted. He loved sharing his passions with other people. We all had been worried sick about Rush’s health ever since his diagnosis. It is unquestionably the case in my mind that the tens of millions of prayers extended the man’s life beyond what was scientifically possible. So what did we give the man who had everything? Our family, Rush’s friends, and Americans across the country came together and gave him our hearts.

Shortly before Rush’s father died in 1990, an exchange was recounted to me by my grandmother. Having seen the beginnings of his son’s national success, a very sick Rush Limbaugh Jr. was asked by my grandmother “so what do you think of Rusty (his family nickname) now?” Rush’s father solemnly replied, “I think he is a genius.” These were words that were never directly expressed to Rush by his father, and when I shared this in an email to him a decade later, it received no response. I did however notice in Rush’s library one Thanksgiving that a large portrait of his father had been placed on the wall above his desk. There is little more gratifying than proving to a parent that they did a good job, and you turned out ok.

The last email I received from him was in response to a piece of music I had written for his 70th birthday. “I am so sorry I am late thanking you. I’ve been in the hospital all week and still am. But I really do appreciate this Stephen, so much. You are just one heck of a great guy and I’m honored to be in the same family”—the final encouraging nod of approval. Rush was my mentor and a champion of my work, but most importantly, he imbued in me a sense of wise direction, establishing my True North. That is the real tonic of artists, which Rush knew as well as Beethoven or Shakespeare. For the rest of my life, there will not be a day that goes by where I will not think of him.

As we reorient ourselves in this new wilderness, we must all now commit to one more thing for our dear Rush: the preservation of his legacy as it originally existed. It must never be adulterated, rewritten, or appropriated so that future generations shall know him as he was. As students of history, we understand the natural rise and fall of civilizations, so our duty is set, and our hearts emboldened: this great country may fall, and the world may die, but Rush Limbaugh will live on forever.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Conservatives would be mistaken to throw Rush and his fans under the bus.

A reply to Chris Caldwell.