The Fellowship of the Right Wing.

RIP Globalism, Dead of Coronavirus

Internationalism may be hazardous to your health.

Update: a few hours after we received this essay, the White House announced its China travel ban. Mr. Yarvin tells us he is delighted to be proven wrong. He adds that electing Republicans has always meant electing the exception that proves the rule. And among our most senior bureaucrats, too, he claims perhaps unconvincingly, are secret reservoirs of wisdom beyond ideology…whose gates open only in an emergency…which will be dry, anyway, in twenty years. But he will go and take his white pill now.—Eds.

TLDR: as I write (January 30th), there is no good reason for anyone to be flying across the Pacific. The same may soon be true of the Atlantic. And certainly, no one should be flying in or out of mainland China—except via a quarantine facility.

This observation is obvious and any fool can see it. A fool always says what he thinks, and all the fools are already saying it. As usual, this helps no one—not even the fools.

And Western public health authorities, though their epidemiology remains first-rate, cannot say this, or even think it, because of their internationalist intellectual doctrine, just one aspect of the great American progressive tradition of government.

They cannot even remain silent on it. Just today, they have said just the opposite. “WHO advises against the application of any travel or trade restrictions on China.” Always trust content from international institutions.

Modern leaders cannot think for themselves. They cannot trust fools. They have to trust international scientific institutions. They are and must be existentially dependent on the collective accuracy of the global scientific community.

These are just the rules. This is the real constitution—the way government decisions are actually taken. Even an absolute madman of a President can only violate this real constitution so many times. (And how he chooses those times says a lot.)

At the moment, what Western scientists are saying about the virus may be slightly understated but is generally true. What Western scientists are saying about what Western governments should do about the virus (by Chinese standards, nothing) is strange and unsound. The Chinese regime is right to ignore them.

Pervasive error means politics corrupts everything it can. Politics cannot corrupt virology. It can corrupt public policy. Its virology is science. Its public policy is…weird.

For this virus, there is no way our experts could rethink that public policy in time. Either we get lucky, or the virus is replicating in America within a few weeks.

The proper attitude is just to observe the tragedy as it happens—if it happens. How can we act? We have not even started to learn to observe—much less plan. And the best plans are long. History is pure because no one can act on the past. Present history is hard because one can.

Or so it often seems; but this is hardly ever so. Before we can even begin to observe the world around us, we must develop the ability to read the present as immutable, like the past. Only those who have mastered this art, which now and for the foreseeable future is no one, can consider suspending it. This remains true even in the moment of a likely tragedy.

Background

In October 2019, epidemiologists at Johns Hopkins ran an exercise, “Event 201,” which modeled a coronavirus pandemic. It went completely wild in the Third World and killed 65 million people. Every virus is different, of course. The model virus was more lethal than this one—maybe not 10x more lethal.

A coronavirus is basically a cold. The “novel coronavirus” is a cold that gets into your lungs and causes pneumonia, which kills old or sick people. It seems to hit children more lightly, which may be good or bad. Any parent knows the sniffly toddler is a biological weapon.

We could get lucky

China, as an autocratic total state, may have the world’s highest state capacity for disease control.

The Chinese government was able to contain SARS because SARS patients aren’t infectious until they have a fever. The government covered the country with fever-checking stations—and it won. China’s latest numbers are distinctly subexponential; epic lockdowns are hard to sustain, but must have a huge impact on viral replication; its scientists may not be quite as good at making vaccines as ours, but paperwork will not get in their way; China has a chance.

Coronaviruses prefer winter—spring is coming. They mutate fast—this one could decay into a harmless cold which is also a live viral vaccine, immunizing us against its evil cousin. Nature has a chance.

God, as Bismarck said, takes care of fools, drunks and the United States. God always has a chance.

Suspending 1492

But as another statesman said, the purpose of government is to provide against preventable evils. What if God has had enough? What if nature is a bitch? What if China has no chance?

We could be lucky! Let’s hope we get lucky. But—right now (January 30), the world’s top epidemiologists and virologists seem to concur that we will need to be lucky. And in these professional, social and intellectual circles, the penalties for showboating alarmism are dire.

If this turns out to be so—and we may not know for sure until it’s too late—the USG could save millions of lives, American and foreign, right now, by suspending 1492 and disconnecting our planet’s two great hemispheres. Epidemiologically, at least.

The obvious solution to an emerging pandemic killer cold is cutting off flights to China, then all air travel across the Pacific, then across the Atlantic—depending on the virus’s progress, and maintained donec sciam quid agatur. Slower quarantine facilities can get trapped people home.

Obvious thinking, of course, is sometimes wrong. It cannot be described as scientific thinking—and here is the problem.

Indeed the Western public-health community tends to feel that naive isolation measures, popular both among their old European ancestors and their present Chinese competitors, are barbaric, inept and wrong—like treating cancer with bloodletting.

They are even well aware that, to the uneducated, they sound like the mayor in Jaws. No, our public-health experts have not been corrupted by the travel and hospitality industry. They say what they think because what they think is the latest science. It may not be good and true; it is as good and true as it gets. And they have a stack of papers as tall as you to prove it.

This dialectic is so thick, you could cut it with a knife. As in any really fresh dialectic, both sides are obviously right.

An unexpected context of decision

Western leaders have to listen to the best scientists—that’s how our process works.

They don’t have to listen to the West’s best scientists. They could listen to China’s best scientists. But this would introduce its own well-known source of political distortion.

Or they could listen to Hong Kong‘s best scientists—who are somewhat outside both Western and Chinese distortion fields. Bureaucratically this still doesn’t really work. Intellectually, let’s try it and see how it goes.

“Substantial, draconian measures”

Ready to spend half an hour watching TV? Do you know that TV trope where the scientists, having run the numbers, come out to tell the world that—the world is doomed? Here is that press conference, IRL—January 27, 2020. Watch the whole thing.

The West’s best epidemiologists consider this Hong Kong team peers. They have the most hands-on experience in the area, having dealt with both SARS and bird flu. They are relatively immune to ideological pressure from both the West and China.

Their message is not that the coronavirus will become a pandemic—just that they do not know what would keep it from becoming a pandemic. As Dr. Leung puts it:

There is already self-sustaining transmission in quite a number of Chinese cities. Because we have at least four city clusters around the country that have extensive links with the rest of the world’s airports, then the chance of seeding sufficient numbers in overseas cities such that they would generate their own epidemics, is not trivial.

Dr. Leung says: if asymptomatic patients do not shed much virus, as in SARS, “we might have a fighting chance.” Considerable evidence of asymptomatic transmission has since appeared. (The experts are still guessing, but the virus seems to have a large “iceberg” of mild but contagious infections.)

As for his policy recommendations, Dr. Leung thinks the internal Chinese quarantine is too late. For the rest of the world, his recommendation is simple if not specific.

“Substantial, draconian measures limiting population mobility,” says Dr. Leung, Hong Kong’s top guy, both a virologist and a virus-fighter, “should be taken immediately.”

Hong Kong has no ocean borders, but has since taken Dr. Leung’s prescription. We like to remember Athens because of Pericles, not Draco. But only one of them died in a plague.

Our interconnected, globalized world

On the same day, January 27, the NYT published an op-ed on the same subject, by a leading American public-health expert. Dr. Markel—a trained pediatrician—has studied both science and history; he can certainly turn a phrase.

His timing is so good that he has a book to sell: Quarantine. Quarantines and other isolation policies, we learn, are bad. Don’t miss the part of the op-ed where he tells you that his historical research says quarantines work, but are bad anyway.

And Dr. Markel’s policy prescription is the opposite of Dr. Leung’s: “Incremental restrictions, enforced transparently, tend to work far better than draconian measures, particularly at enlisting the public’s cooperation, which is especially important for properly handling outbreaks in our interconnected, globalized world.”

Dr. Markel is no more a political scientist than a virologist. But he does know the lingo, doesn’t he? This virus mainly seems to kill old people. So this is the kind of thinking standing between the boomers we love, and drowning in their own fluids.

To keep up with the Hong Kong consensus, get your plague news not from the Washington Post, but the South China Morning Post. When Dr. Leung turns optimistic, you can chillax. If he dies, stock up on ammo. Anything that sounds like Dr. Markel can be ignored.

Deconstructing internationalist bias

Why does this kind of banal, vague, even mystical thinking, so seemingly dangerous in a crisis like this, have such a strong hold on the Western scientific mind?

Why exactly have Dr. Markel and his ilk wound up as the mayor in Jaws? What led them to this place? What is internationalism? That’s a long conversation, because internationalism is older than any of us. If you are somehow older than John Lennon, check out Wendell Willkie’s 1943 bestseller—One World.

(Yes, “internationalism” is the same thing as “globalism.” It’s a better word, because it isn’t a slur. Any label for any group that the group does not use itself is an actual or potential slur. It is particularly unwise for the weak to slur the strong. I may be biased, since I myself was raised as a “globalist”—to be exact, a Foreign Service brat.)

Here is the shocking secret bias motivating our public-health experts. One: they are deeply passionate and principled people. Two: they have a single shared purpose—to make the world a better place. Three: they share a deep, almost spiritual belief that a more open and interconnected world will be a better world.

They are still scientists—excellent scientists, generally. Not all of them are pediatricians. They do not attribute their general disapproval of isolation and quarantine to their fondness for John Lennon songs. Their case against medieval public-health measures is expressed in terms both scientific and realistic.

These experts hold their ideas because those ideas are hypotheses that have succeeded in the scientific marketplace of ideas. For those who spent high school smoking out behind the goalposts, this is how all scientific “truth” is established.

If this process did not work, your computer would not work. But if it broke, not even everywhere—would your computer break?

In a doctrinally homogeneous scientific market where every expert is or must pretend to be an adherent of some doctrine—whether Christian, Communist, or Nazi—ideas may earn as many points for doctrinal as logical strength. As we learned from the 20th-century regimes in which power distorted science, this bias, iterated, can evolve almost arbitrary levels of consensus error. Even good, red-blooded American ideas, such as internationalism, are capable of catalyzing this reaction.

How does a doctrinal bias work? The more strongly you support a sports team, the more strongly you think the refs are biased against you. This is called “motivated cognition.” What happens when the call goes against your team is that you look much harder for reasons the referee is wrong, than for reasons he is right. Your critical standard for arguments for your team is lower.

As an internationalist, when you see ideas which whatever their purported good result would move the world backward—forward being toward more unity and interconnection—you are disposed to look for reasons why those ideas, while obvious, are somehow subtly and elegantly wrong. And when you judge these reasons, you lower the critical bar. Libertarians do the same thing for libertarian logic; motivated cognition is just human nature.

The harder these subtle arguments are to discover, the more tenuous they become—and the more numerous. They often contradict each other, in the classic “Racehorse Haynes” style. Thus we are told in one breath that isolation does not work, and the next that anyway it is too late for isolation to work.

Until they come up with some theory of how a fragile virus can hop from the Old World to the New, without hopping on a plane, there is no point in trying to refute the internationalists. They can only be deconstructed. As a Brown graduate I am trained in this chic ’80s martial art—beware.

Why internationalism is cool

It is impossible to reason anyone out of any belief that they weren’t reasoned into.

Since American internationalism is older than you, you were not reasoned into it. Like any doctrine, internationalism was a universal belief in your society before you were born. You learned it as unquestioned truth both at home and at school.

Since modernity is a social acid, this explanation is incomplete. All religions or traditions work this way: as dogmas. In the 20th century, they almost all got eaten alive. Internationalism is an old dogma. It must be more than an old dogma or it would have gone the way of all the other old dogmas.

But internationalism, though old, is cool. Why? For two reasons.

First, internationalism is in power, and power is always cool. As another statesman said: when people see a strong horse and a weak horse, they like the strong horse. If Catholicism had just as much power, it would be just as cool.

This desire to follow and submit to the strongest power, Greek pistos or loyalty, is a human universal. As we see when we look at Nazi science or Soviet science, scientists are humans. Even the most talented and conscientious scientists are humans.

But scientists, by their nature, are also leaders. We might call them elites—nobles, even. Elites, as an essential aspect of their general eliteness, have another desire: not just to follow power, but to wield it. This is also a natural human urge; the Greeks called it thymos or ambition.

Loyalty and ambition can both be righteous. But both can go wrong. When loyalty goes wrong, it becomes servility. When ambition goes wrong, it can become cruelty, vanity, or both.

How is internationalism ambitious? College bookstores everywhere groan with texts on the hegemonic nature of internationalism. It is unnecessary to restate their clichés. The theory is sharp enough, though never used on sacred cows.

With respect to China, for instance, one might note that if we compare Beijing in 1880, Boston in 1880, and Beijing in 2020, in many ways the third looks more like the second than the first. A Chinese mandarin of 1880 might notice that his descendants were wearing Anglo-American clothes, and wonder why. Later he might learn that his country, after an American-style revolution, would settle on a political theory composed in the British Library. Clothing is a sensitive indicator of general fashion—which is a sensitive indicator of general power.

And when internationalists think about the world becoming more interconnected, they think about it becoming more American—certainly not more Chinese. We are imposing our ways (which are superior) on them. We are turning them into copies of us—excepting only the things we can’t change, like skin color and language.

The WHO chairman is from Ethiopia—is he issuing decrees in Amharic? Applying Ethiopian ideas of public health? As an intellectual, this man is an American. That he looks and talks a little different doesn’t matter to his colleagues; why should it matter to us? An American education has given him as complete a culture transplant as any Ottoman janissary. There is nothing non-hegemonic about this picture.

Regarding China, perhaps American arrogance made sense a century ago. The Qing Dynasty did have some issues.

Today, regardless of its ethical merits, hegemonic internationalism is inconsistent with political, commercial, and financial reality. That today it seems to be inconsistent with epidemiological reality should not surprise us; it would not have surprised the Qing. Epidemiology was always a great reason to be isolated.

Yet we find internationalism so emotionally attractive that we cannot abandon our dreams of Americanizing the world, even to defend ourselves against a deadly virus. Internationalism is sexy because it casts us as the teacher, the parent, the master. One might even say—the missionary.

And we are not villains; all our actions are actions of love. Our hegemony is not world domination. It is global leadership. We are both yin and yang—the mother as well as the father. Internationalism makes us symbolic parents of the whole world: a heavy trip indeed.

Thymos is a powerful drive which is easily compared to eros, the sex drive. Ambition too is subject to pornography; when it is inherently futile and fruitless, ambition becomes vanity. Vanity is a hell of a drug.

Internationalism is not even our century’s dream. Its roots are deep in the 20th century—perhaps even deeper. The secularized missionary vision of America civilizing the world by educating, developing and pacifying it, the plan FDR called his “Grand Design,” is as distant from reality today as Don Quixote from medieval chivalry.

When you’re a good and serious person doing good and serious things, but the world your senses perceive does not correspond to objective reality, you can do a lot of damage while trying to do good. Don Quixote’s lance is a real lance.

And that’s how internationalism could quite easily kill millions of people this year, without anyone actually trying to be evil.

It is always wrong to think of doctrines or governments as malignant demons. They are not—any more than viruses are. At their worst, they are only machines to be fixed, replaced, or abolished. If internationalism actually does this thing—it will still not be abolished.

But it should be.

New visions of isolation

Isolating the hemispheres, blocking human travel between Old and New Worlds, is a temporary measure for a temporary epidemic. Its motivations are utilitarian and transient. Only at very specific moments in very specific situations is it appropriate. One of those moments and situations might be right now—or not.

Right now, if this is so (and it may not be so!), this simple and obvious action needs no ulterior motive. It needs no telos, end, vision, or utopia. It is just about life and death.

And yet—any political action demands strength. All actions must be taken as strongly as possible. This action, like any other, will be stronger if it can present itself as the first step on a long and difficult road to some incredible dream. I actually believe in this dream; but then, I would.

Refusing to refute internationalism, we have deconstructed it. We need to compete with it—to define an isolationist vision.

This vision should be as radical as possible. In private, even the earliest internationalists of the 20th century thought much the way their successors think today. Their speech was often cloaked. Their minds would have been at home in 2020. They started out by thinking as far ahead as they could. And why not?

As with any temporary measure, an interruption in transoceanic travel—or any other epidemiological partition of the planet—must run some risk of becoming permanent.

Perhaps the virus cannot be eradicated in the Old World quickly. Perhaps it cannot be eradicated at all; it becomes endemic.

Then the hemispheres are not just decoupled, but miscoupled. Any travel is epidemiologically dangerous to one or both sides. Of course this was exactly the situation in 1491. There is no safe and easy way to restore global travel.

Should we expect miscoupling to spontaneously fix itself?

It might; or humans might fix it; or subsequent epidemics might make contact more and more dangerous. We are in sci-fi territory. But imagine a world where travel between hemispheres is cut off next week—and stays cut off for years, decades, centuries…

Would this be a disaster? No—it would actually be fine. It would not even change much about most peoples’ lives.

Skype Isolationism

Dr. Markel and his ilk talk about our deeply interconnected webs of “travel and trade”—as if 21st-century trade involved some Fuller Brush salesman from Tucson pounding the pavement in Wuhan.

The irony of this stale propaganda (for why else would the WHO statement mention “trade”? Have coronavirus-infected blankets been found on Amazon?) is that never in human history has physical travel been less necessary to either trade or communication. Even science can be done over the Internet!

True, in business, it is still best to be there in person. I myself once worked for a Japanese software company—not for very long. I also just bought my son a toy quadcopter from a Chinese website. This trade caused no human travel. If needed (this virus is fragile), cargo could even be irradiated.

Conferencing still kind of sucks. It could be improved—maybe with, like, VR? But while the imperfection is significant, it is not ultimately material. It is not worth one human being choking to death on bloody soup—let 65 million, or even 6.5 million.

And what’s left? Visiting the relatives? Use Skype. Or send a letter. The letter, too, can be irradiated.

Tourism? Tourism is vile.

Science and education? Scientists and students, too, are capable of collaborating digitally.

Diplomats? You know, Woodrow Wilson had this great idea—”open agreements, openly arrived at.” What would that mean in the 21st century? Could it be done on—the Internet?

Whether its boundaries are enforced by oceans, walls, minefields, or crocodiles, an absolute partition of the earth into regions of human travel—or a partition plus a slow, expensive quarantine process—is simply not a disaster. Even if somehow it has to be permanent, which seems anything but likely.

True isolation is the old Asian way

Travel is only one thread in the web of globalization. Travel, communication, commerce, finance, and diplomacy are the others. Cutting off travel is easier and stronger if we have at least some conception of what it might mean to cut the others.

FDR’s domestic opponents were accused of being “isolationists.” This was a slur. They were neutralists. They believed in a multipolar world order, the Farewell Address, and classical international law.

But true isolationism is a real thing. It is not an American thing—but can’t all things become American? Originally, it is an Asian policy—the original policy of the Chinese and Japanese old regimes toward the West.

These countries generally prohibited both trade and travel—none quite perfectly. Japan’s sakoku was perhaps the strictest. No one was allowed to leave Japan and return; a fisherman cast up in Alaska had to stay in Alaska.

China was “opened” involuntarily by the Opium Wars, like Japan by Commodore Perry. Perhaps it is time for the West to finally recognize that China was in the right. Either side, of course, can unilaterally impose a policy of isolation.

China has a long history with American internationalism. Deep cultural and historical links unite the Davos men of today and the high-Protestant missionaries of the Rockefeller era. The postwar “aid-industrial complex” is the prewar ecumenical missionary movement—and in no country’s history is that clearer than China’s, with its huge missionary presence.

The damage from China’s imported revolutions was immense, and included the physical destruction of much of its heritage. Is it an accident that a foreign ideology tried so hard to destroy so much that was authentically Chinese? It is a historical fact that Beijing, in so many ways, became Boston. Recognizing this fact need not mean celebrating it.

Neo-Sakoku

Imagine if 19th-century Englishmen and Americans had said: China and Japan are ancient and beautiful nations. The duty of each nation toward every other is to help it flourish, in whatever way it chooses—the duty of a neighbor, not a friend.

Our ways are not your ways. We like to trade. We like to lend money. We like to sell opium. You do not like any of these things. Your way is one of isolation. As good neighbors, when dealing with you—your way will be our way.

Isolation is always qualified. Late premodern China and Japan were willing to accept our science and technology, mostly; they were willing to trade, a bit; what they really wanted to avoid was cultural and political contamination. And no wonder.

Had the Western powers honored the wishes of the Qing Dynasty and Tokugawa shogunate and not only complied with these policies, but cooperated in enforcing isolation against their own citizens, the historical treasures—human and physical—of these ancient civilizations would still exist. What internationalist can stand up and call it good that we destroyed these societies?

Instead we have Boston, made out of Japanese people, occupying the Japanese land, speaking Japanese, with a slight but genuine Japanese flavor to their culture. Modern Japan remains the most non-Western country on earth. Compared to pre-Perry Japan, it is still Boston. After Boston it owes the most to…Prussia. And more in Japan survived the war than in China after the revolutions.

How can internationalists not see what Solzhenitsyn saw: that every human nation is a priceless jewel that humans can smash, but not create? We understand this principle with a species, a language, or even a building. On nations, we go full Taliban.

Of course, a jewel once smashed is—smashed. But every human wound heals; not always fast, and only once the wounding ends. It is an accident that we might have to cut off travel between partitions of the world. Might not that accident inspire us? Might not we see some healing, and want more?

Might not we say: our species is made richer by its differences? But, if we try to blend all of these ways to be into one way, we either destroy all but one—or end up with bland, beige mush. This rhetoric, although not orthodox, is mere inches from orthodoxy.

No one actually plotted to blend the world. It was going to blend itself. As our mastery of nature grew so strong that humans were able to essentially teleport, the borders which once were real became lines on a map. They once enforced themselves.

Now, if we want our borders to be real, we need to actually make them real. Locality is a simulation; but locality is no less essential. Humans must do the job we have stolen from nature.

But to a substantial extent we have done that. But this only assigns us the responsibility of beginning to reverse it. So—why not go on cutting those threads of the international web? What else can we cut? And how can we cut it?

If in the 20th century it was wrong for America to burn down the world, in order to turn it into Boston—if in the 21st, America acknowledges that it can neither solve this problem for the Third World, nor needed to for the First—if America, drawing on some deep well of wisdom hitherto unplumbed, should even go so far as to regret trying—then it remains our duty to not only cease this crime but, as the empire is wound down, to repair it.

This means not just tolerating isolationism, but promoting it. And true isolationism, as the Asian old regimes showed, can go far beyond mere travel disconnection.

There are many threads in the international web. Or perhaps—a spiderweb? What if we cut them all? Could we cut them all? Could we at least imagine cutting them all?

The principles of neo-sakoku

What the old regimes had discovered is that cultural, political, commercial, financial, and technical ties are hard to separate. Once one country develops an unequal relationship with another, power tends to flow in the same direction along all these wires. Cultural power favors the strong, and Beijing turns into Boston.

How can unequal nations share a single world? Easily. They can pretend to be on separate planets—possibly even in separate galaxies. If the governments of two nations agree to prevent all contact between the nations, exactly as if they were in different solar systems, the two cannot even have a beef.

This state of absolute isolation is not generally ideal. But if we need one relationship that clearly combines unconditional independence with unconditional peace, absolute isolation is always available. Any country, at any time, can or should be free and able to isolate itself completely from the world.

This will remind some of the Cold War. But the difference is that the Iron Curtain, or even the surviving North Korean ideology of juche, was a fundamentally hostile barrier.

The geopolitical goal of the whole Communist world, now and then, from the USSR to the DPRK and even China today, is to survive—to remain independent and sovereign, and not become assimilated into the “international community” or American empire.

If a regime can defend its independence only by hostility, hostility is an inevitable consequence. Every hostile regime is ugly. Internationalism is the ultimate cause of this ugliness. The North Korean leadership literally has no choice but to continue its hostile tyranny; any surrender means prison or death, and any relaxation means revolution and surrender.

Instead, if the rest of the world truly recognizes a regime, and that regime truly desires a policy of absolute isolation, the rest of the world has a duty to help enforce it. Not only do the governments of the world not try to break the blockade; they restrain their own citizens when they try to break it.

Within the isolated nation, mutual isolation creates a totally different vibe—that feeling that the rest of the world is a different galaxy. Neither hostility nor adoration toward any foreign country has any remaining meaning. Both the nation and its citizens are so far from their old international crushes and beefs that it contemplates them with no emotion but vague regret, like a college senior thinking about high school.

And if they do somehow scale the wall, the other side will just send them back. The rest of the world is right over there. It is not another galaxy; but it might as well be. No one can get anywhere by trying to break the abstraction—and since after a while no one even knows what is across the wall, no one tries; everyone stops caring; and true psychic independence is achieved.

This independent mindset was Jefferson’s goal in his embargo on both England and France. Jefferson’s embargo is not usually regarded as a success. Jefferson was often ahead of his time.

The purpose of neo-sakoku

Suppose everyone does this. They take the most “substantial, draconian measures” imaginable. The planes are grounded. The cables are cut. The container ships rust at anchor. Even the holy dollars no longer flow. Every country now has the foreign policy of North Sentinel Island.

But why? Is neo-sakoku anything but a giant act of vandalism?

The nation, absolutely isolated, has no choice but to develop on its own—politically, economically, culturally, artistically, industrially, and scientifically. Every nation in the world has its own elite capable of working in all these areas at the highest level, though it is not always a large elite.

Consider industry. If any citizen of an isolated nation wants to use something, that thing must be made by some other citizen of that same nation. What are the effects of this change?

Next to today’s global supply chain, this change creates an enormous drop in productive efficiency and consumer utility. All of Western economics, from Marxists to Austrians and everyone in between, believes that the purpose of an economy is to maximize the production of luxury—literally what we mean by “GDP.” So all 20th-century economists must consider neo-sakoku very bad.

But this same policy creates an enormous increase in labor demand at every skill level. No one’s hands can possibly be unneeded. And if many difficult technical problems were formerly solved by foreigners, there is no shortage of challenge.

As another statesperson has said, the purpose of an economy is to make everyone flourish. Some people can flourish without being used, needed, or challenged. These people, we must admit, are superior human beings. There are not many of them.

Cutting off transpacific travel does not cut off transpacific trade. It does not even cut off transpacific fentanyl. Yet if trade (and fentanyl) are also cut off—and this cutoff is credible, effective and permanent—what happens in the US?

The first effect is an enormous shortage of consumer goods. All kinds of plastic junk will be expensive or unavailable. Some kinds of junk may even develop a used economy for trading and maintenance, like old cars in Cuba.

The US is not Cuba; its government is stronger, and can permit capitalism. Cuba is not without native talent; if it could make the same economic leap as China, it could build cars. The US has both talent and capitalism; it has some issues with paperwork; it can still make more or less anything.

So the second effect is an enormous import substitution boom. Whole industries and supply chains need to be rebuilt. And a trillion dollars a year, previously banded, bagged and mailed to China, Japan and Germany, is now paying Americans to work.

And for anyone who needs something to do, rebuilding a whole industrial sector is rain in the desert. And no one needs something to do like a junkie who can no longer score junk.

Thus can the involuntary isolationism of an epidemiological disaster be gently reimagined into one of history’s beautiful accidents.

These kinds of measures, obviously, are in no way practical in our present political reality. They cannot even be considered à la carte. Just as internationalism is just one piece of a larger vision, so is either kind of isolationism.

The praxis of neo-sakoku

Even assuming some imaginary absolute world government, any transition to a deep multipolar order, in which every nation both holds and maintains maximum substantive independence, is an enormous challenge.

Today’s non-independent nations are connected by a web of dependencies. If these threads are cut without mitigation, many countries would catch fire and explode.

Many countries are dependent on foreign food. Many countries are dependent on foreign loans. Many countries are dependent on foreign industry and technology. Many countries are dependent on foreign markets. Many countries are dependent on foreign medicine. Many countries are dependent on foreign materials. Many countries are dependent on foreign security.

Absolute isolation is seldom practical, especially from a cold start. The art of “neo-sakoku” is designing policy solutions that achieve the same general result, but with exceptions that compromise the goals of isolation as little as possible.

The unfinished tablets

There is no simple solution to any or all of these problems. But the real Machiavellian purpose of Skype isolationism and neo-sakoku does not require that it happen right now. It is to present a long, clear, and beautiful road in front of a policy much, much simpler, which should happen right now but probably won’t.

The unsolved problems are not even a flaw. They are beautiful.

They give a doctrine an open, infinite character—very suited to the modern audience. It is not on stone tablets. If it is, there is plenty of room left on the stone.

There is plenty to be done. Long before that, there is plenty to be written.

Don’t we all want to matter? To have big ideas? This is the way to compete with internationalism: beat it at the fundamental game of giving elites a way to feel important. The winning doctrine is always sexy, true—and incomplete.

What can such wild, futuristic dreams mean to a decision that will mean nothing unless taken in the next two weeks? Nothing, for no such decision will be taken.

But if we learn to dream such dreams—well, perhaps they are good.

I think they are good. Your mileage may vary. It is neither here nor there; we cannot possibly know for decades.

This dream, not built as a tool, is a tool for the present. It is built to replace the old internationalist dreams of the 20th century.

Man needs dreams; they cannot be removed or refuted, only replaced. With big dreams we can act in small ways. But if the dreams are built for the act—they will be small.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

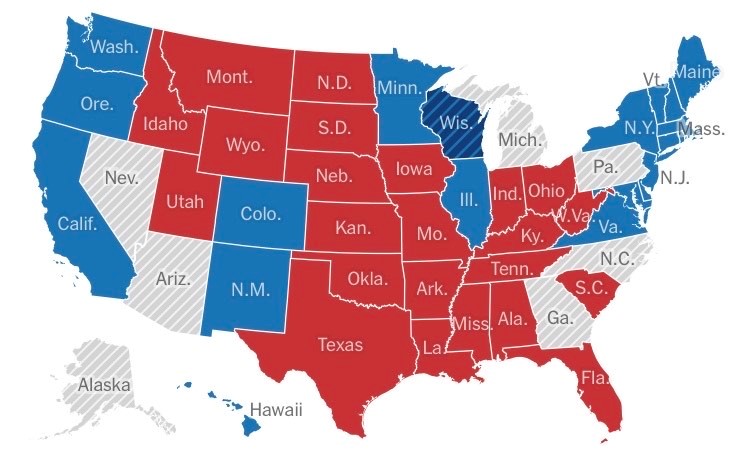

The Claremont Institute's pre-election war games have proven prescient so far.

A government agency seeks to delegitimize conservative politics.

Pocketbook concerns override racial resentment in the current political climate.

Reviving the Hamiltonian spirit in an era of populism.

Democrats have met with a problem that messaging can’t solve.