Resurgent national sovereignty movements are back and validated by expanding electoral mandates.

Professor John Eastman’s Response to the Latest Manifestation of Chapman Cancel Culture

John Eastman was asked by the President of the United States to represent him before the Supreme Court of the United States. Eastman is a law professor at Chapman University (though on leave this year while he is serving as a visiting scholar at the University of Colorado Boulder). Following Chapman’s established rules on the filing of briefs by law faculty, Eastman included his official bar address on the brief, which is his Chapman University address, phone, and email. At the request of the Law School’s Dean, he removed the name of the institution from the address, leaving only the physical street address, phone number, and email, as required by Supreme Court rules. Nevertheless, the left-wing faculty at the University howled over the brief, and the President of the University publicly chastised Eastman for his use of his University phone number and email on the brief. Below is Eastman’s reply. – Eds

“Wow. A member of our faculty—a colleague—was asked by the President of the United States to represent him before the Supreme Court. The President of the United States! What a tremendous recognition of his professional accomplishments and national reputation.”

Imagine had the President making the request been Barack Obama. The Chapman University community—the Trustees, the President, the faculty all—would have been shouting the accomplishment from the rooftops. A cover feature story in the Panther Magazine would likely be forthcoming. Heck, the annual American Celebration might even feature such a renowned professor.

But instead, because the President at issue was Donald Trump, who invokes a visceral hatred from the overwhelmingly left-wing faculty on campus (yes, you read that right), howls instead of cheers rang out when my representation of the President became public. Wylie Aitken, Chairman of the Board of Trustees, claimed that the case had “no merit” and that my representation of the President of the United States was “embarrass[ing] the University.” Then, blind to the irony, he claimed that “Chapman is dedicated to bettering itself as a diverse and equitable university”—a diversity that, apparently, does not include political or ideological diversity.

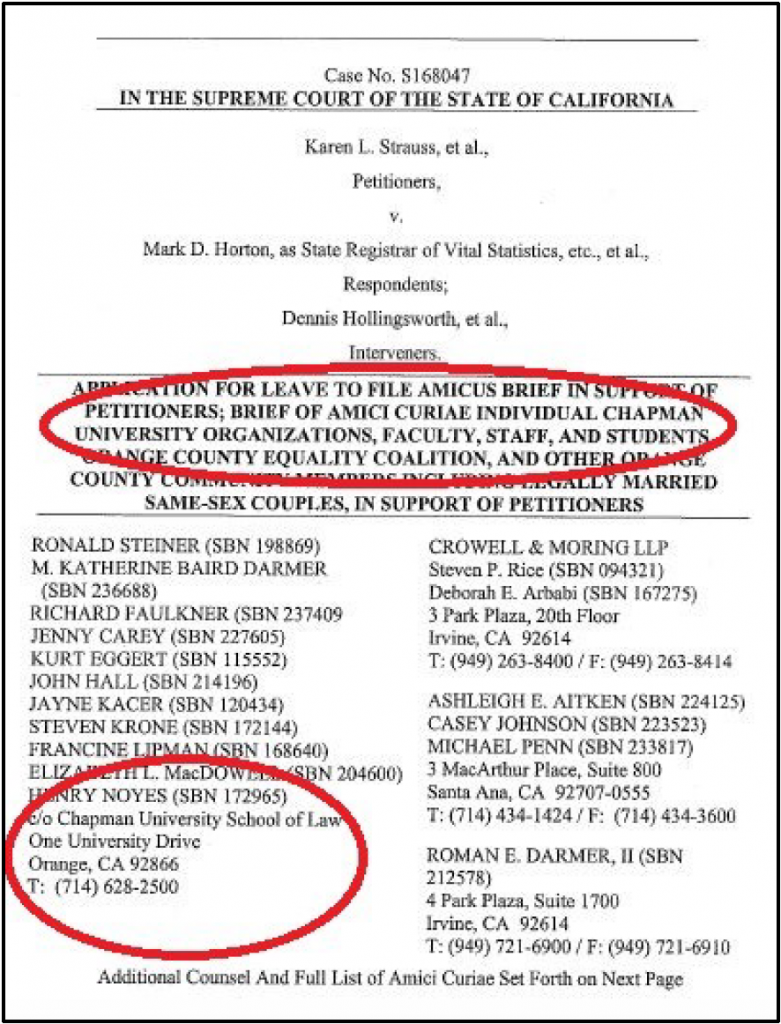

Fred Smoller, Associate Professor of Political Science, claimed “that by associating his Chapman credentials with the lawsuit, Eastman is undermining university ideals of pursuing the truth.” What a preposterous double standard. Our faculty—particularly our law faculty—routinely list their professional address on court filings; indeed, the University pays our bar fees because keeping a hand in the practice of law is extremely beneficial to our students and part of the expected duties of our faculty positions. Our University address is the official address of record for the State Bar (and for those of us who practice before the Supreme Court of the United States, the official address of record there as well). Here’s another high-profile example:

I do not recall Aitken, Smoller, or Lori Han complaining about that brief’s use of the Chapman address or, even more blatantly, the fact that the brief was being filed on behalf of “Chapman University Organizations, Faculty, Staff, and Students,” among others.

A directive did come down from the University Counsel, warning against making it appear that Chapman itself was taking a position in the litigation (as the Darmer brief clearly did). But as for the signature block, the University Counsel confirmed that “The words ‘Chapman University’ may not appear on the brief except as part of a c/o address for the author.”

Which is what I had done with my brief on behalf of the President, until I notified the Law School’s Dean that it would be coming, and he suggested that I create even more distance from Chapman in this particular case by removing even the “c/o Chapman” line, leaving just the address and my official contact information on file with the Supreme Court bar.

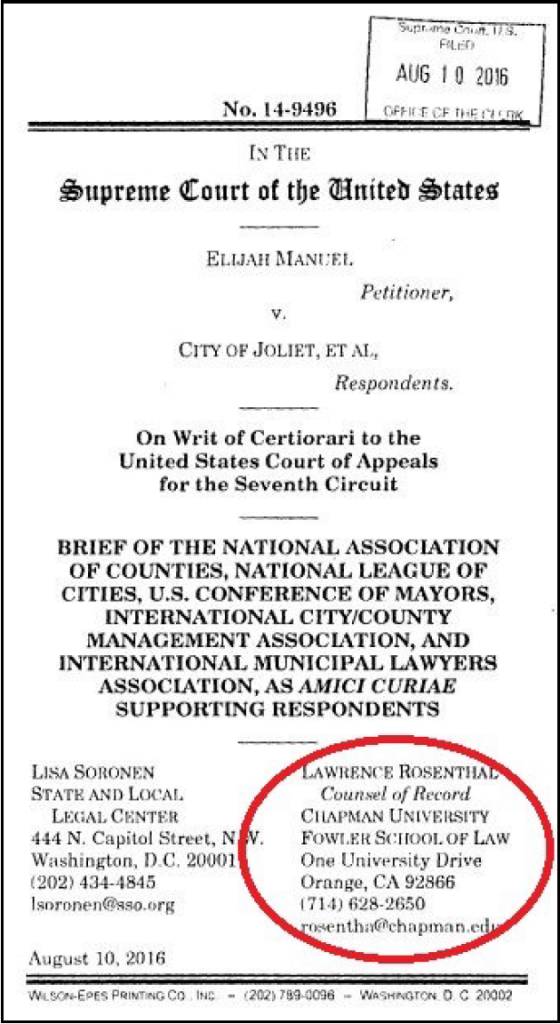

For those who claim that was not permitted, it is in fact commonplace among law school professors. Below is another example from our own Fowler School of Law: Note that Professor Rosenthal does not even include the “c/o” before “Chapman University, yet I do not recall any public letter from the University President demanding that he correct the record.

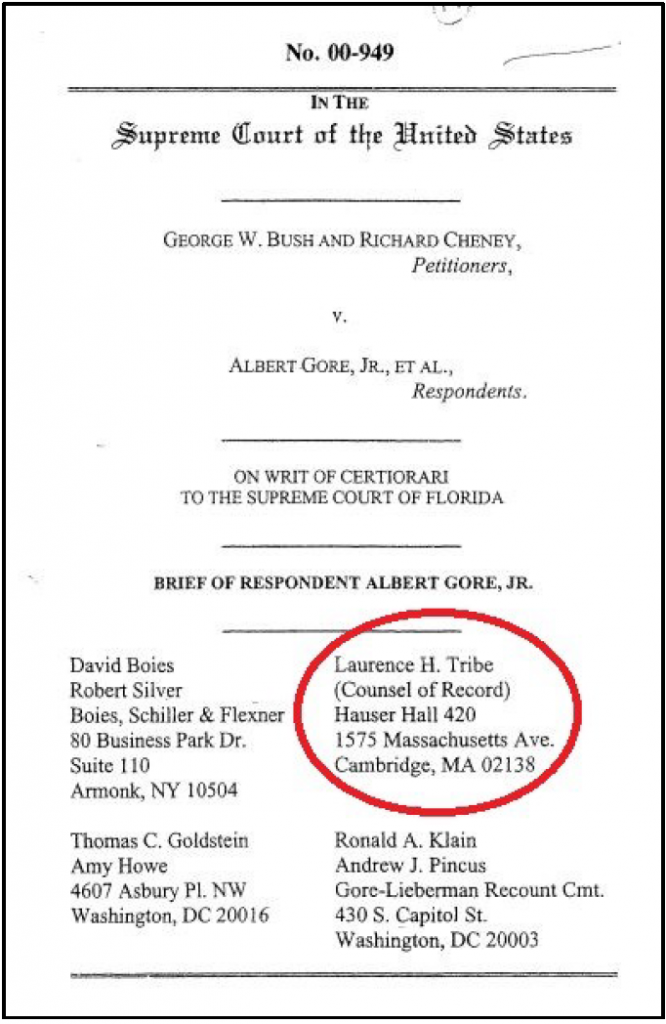

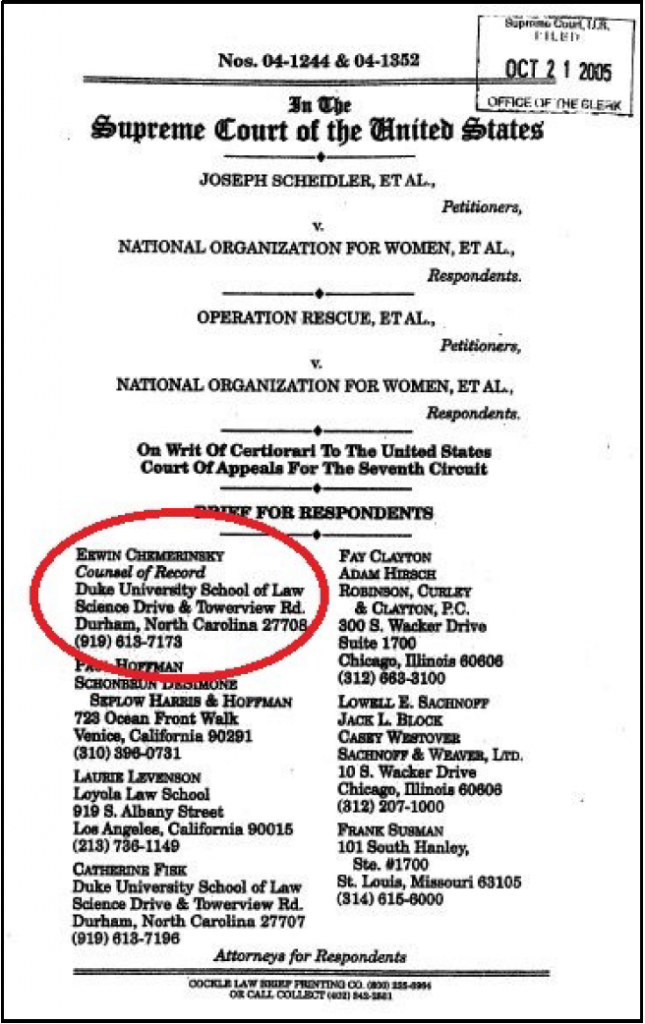

Of course, the Fowler School of Law also aspires to regain our top 100 ranking, so we might consider what other top law schools do. Below are a couple of salient examples (and in case you’re wondering, the address on Professor Tribe’s brief is his office at Harvard Law School). Now it might be argued that my brief is different because, unlike those of Professor Rosenthal and then-Professor (now UC Berkeley Dean) Erwin Chemerinsky, it involves an election matter, but recall that Professor Darmer’s brief above also involved an election matter (an initiative rather than a candidate election, but that is distinction without a difference). In any event, take a close look at the case name on Tribe’s brief—it also involved a little election controversy:

As for Professor Lori Han’s claim that she would not even accept what I wrote in the brief from an undergraduate, what utter nonsense. The brief did contain a minor error; it stated that Trump “won both Florida and Ohio; no candidate in history—Republican or Democrat—has ever lost the election after winning both States.” Apart from the one obvious (and immaterial) mistake on the Nixon-Kennedy election, I challenge Professor Han to point out a single legal or factual claim in the brief that is incorrect. She scurrilously claims that I “clearly [don’t] know a lot about the subject,” so let’s have a public debate about the actual meaning of Article II of the Constitution, the plenary authority of state legislatures to determine the manner of choosing electors, and the significant, unrefuted evidence that partisan election officials in several states simply altered or ignored state election laws in the conduct of the November 3 election. I might also ask her to explain how it is, if I don’t know a lot about the subject, that Legislatures keep calling me to provide expert testimony on the subject, both in the aftermath of the recent election but also of the 2000 election. (By the way, the line in the brief onto which she apparently glommed originally read “never in the last half century has a candidate won both Ohio and Florida but lost the election,” but it got modified during the frenzy of last-minute editing and I failed to catch the change from “the last half century” to “history”. As a further aside, that immaterial error—yes, the point about how Trump won this historical indicator of success stands, whether it was never in “history” or never in the “last half century”—drew a “4 -Pinocchio” comment from the Washington Post, but the Post offered not a word about the material misrepresentations in the state briefs. Georgia, for example, claimed that “the State and its officers have implemented and followed [the election] laws” enacted by the Legislature, but then acknowledged later in the same brief that it did not. Perhaps instead of making false claims that I am “undermining university ideals of pursuing the truth,” Professor Smoller should lead an effort to explore how the major media in this country has become little more than a propaganda machine for one of the country’s two major political parties.

The fact of the matter is that partisan election officials, and in some cases partisan judicial officials, altered or ignored key provisions of state election law. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court did so on the eve of the election and also, stunningly, three weeks after the election. That is a fact. Because only state legislatures have the authority under Article II of the U.S. Constitution to alter the “manner” for choosing presidential electors, those actions were both illegal and unconstitutional. That is the law. When, as with the particular statutes at issue, the laws that were altered or ignored were designed to protect against the risk of fraud in the mail ballot process—a process that the Commission on Election Integrity headed by former Democrat President Jimmy Carter and former Republican Secretary of State James Baker found to be “the largest source of potential voter fraud”—then the legitimacy of the election is rightly called into question.

It would seem to me that partisans on both sides of political aisle would want to get to the truth of what happened here, and what impact (if any) it had on the election results. Repeating ad nauseum that there is no evidence of fraud or illegality, when there is lots of evidence for anyone willing to see, hardly furthers the pursuit of truth. Indeed, it rather reminds me of the famous line from the Prefect of Police in Casablanca, who expressed “shock” that there was gambling going on in the back room as he was being handed his winnings. And attempts by some of my “colleagues” to “cancel” me rather than have an honest debate over the substantial issues that have been raised is hardly conducive to collegiality, or becoming of a University that claims to be dedicated to the pursuit of truth.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Notes on the ground from a soul-sick Santiago.

We will no longer go abroad in search of monsters to destroy.

Mr. B.A. Pervert Knows Leftists Don't Believe in Democracy.

Raising Boys in the Shadow of Endless War

Detractors of nationalism indulge in dreamcasting over statesmanship.