A clarifying exchange.

Presidential Privilege

Jack Smith’s case against Trump regarding his documents is unconstitutional.

The entire premise of the “Documents Case” against President Donald Trump is illegitimate and a direct assault on the Constitution and the separation of powers doctrine. In pursuing 41 felony counts against the president for possessing classified information, prosecutor Jack Smith is engaged in a work of legal abuse without parallel in American history.

A thorough review of the facts, the law, and the Constitution itself indicates that Donald Trump, as President of the United States, had the right to know every secret contained in the executive branch during his time in office. Moreover, as president, Donald Trump had every right to declassify and make public whatever documents or state secrets he chose while in office. In addition, the correct understanding of the separation of powers doctrine makes clear that Congress does not have the right to proscribe how the president is to conduct purely executive branch business either during or after his term. From these premises we can assert that the Presidential Records Act of 1978 is unconstitutional and that any documents discovered in President Trump’s possession after his presidency are presumptively legal for him to possess and dispose of as he sees fit.

The facts of the case against Trump in this prosecution are as follows: after leaving office in January of 2021, Donald Trump retained in his possession a number of documents. Beginning in May of 2021 the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) demanded that Trump turn over documents that they alleged belonged to them. After back and forth with the Trump team, NARA received a number of documents, some of which were marked with classification markings. NARA contacted the Department of Justice in February of 2022 to begin an investigation into President Trump’s possession of these papers. The Department of Justice and prosecutor Jack Smith allege that Donald Trump had unauthorized access to documents relating to national defense and that he is therefore criminally liable for failing to turn these documents over to the government when called upon.

This prosecution rests on a number of absurdities and false assumptions about the workings of our constitutional order.

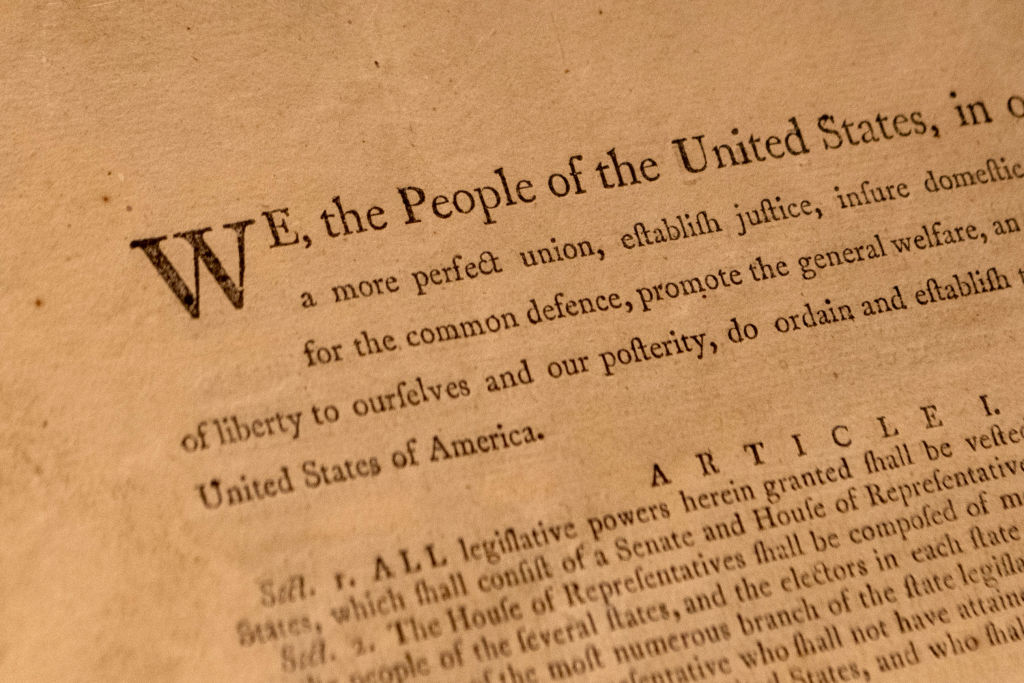

“The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” So begins Article II of the Constitution. We can contrast this statement with the opening line to Article I, describing the powers given to Congress: “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States….”

Note the key difference: the Constitution only gives to Congress the legislative powers “herein granted.” No such qualification is appended to the president’s authority. He is “vested” with the “executive power” whole and entire. No other body within our constitutional framework—not Congress, not the courts (certainly not rogue actors in the federal bureaucracy subordinate to the president)—can strip, modify, or remove the executive powers from the president.

This means that the President of the United States is the executive branch. He is the Department of Defense, the CIA, the State Department, the FBI, the SEC, and the FAA. If the president were a god with a thousand hands he would exercise the work of those entities by himself alone. The president is allowed, under the Constitution, to appoint subordinates to carry out his will as the sole possessor of the executive power that has been vested in him by the Constitution and by his election by the people.

There is a tradition from FDR onward that seeks to undermine the president’s power and to create agencies that possess executive powers but are not under the president’s aegis. This legal logic, spelled out for the first time in the Supreme Court case Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, is illegitimate and unconstitutional.

The text is clear: the Constitution places the executive power in the president. Congress cannot create new executive powers and place them elsewhere in the federal government.

This understanding, flowing from the Constitution itself, is crucial if we are to properly understand the stakes in the prosecution against President Trump. If Congress can create executive powers and place them other than in the presidency, then the branches of the Constitution are not coequal. Instead, the president is entirely subordinate and subject to Congress and to the independent, unaccountable agencies that it creates out of thin air.

The president, in Jack Smith’s framework, is not the chief executive—the text of the Constitution notwithstanding. This is a deeply dangerous doctrine.

We can see the Founders’ understanding of the presidency in the way that presidents treated their documents in the first two centuries of the nation’s existence. Until 1978, the documents created by the president were considered his own private property. George Washington, for instance, took virtually the entirety of his papers with him when he left office, save for those that he, and he alone, thought would be useful for his successor. At his death, he willed the papers to his nephew Bushrod Washington who left them to his cousin George Corbin Washington, who ultimately sold the entire collection to the State Department, which ultimately turned them over to the Library of Congress in 1904.

It was not until the Presidential Records Act of 1978 that this arrangement changed. In order to limit executive privilege in the wake of Nixon’s resignation, Congress passed a law ordering presidents to turn over all their pertinent presidential records to the Archivist of the United States. Section 2202 of that law states, “The United States shall reserve and retain complete ownership, possession, and control of Presidential records; and such records shall be administered in accordance with the provisions of this chapter.”

This law is entirely unconstitutional. It violates both the president’s fundamental rights as well as due process of law—specifically, procedural due process and the ability for the president to exercise authority over any decision within his office without running in violation of the law. Indeed, as designed, the law was to ensure the president would—after Nixon—never again fall out of lockstep with the sprawling federal bureaucracy, whose self-conception is the omnipotent leviathan and arbiter of last resort, the true law of the land, in the post-constitutional order.

Donald Trump never had any obligation to turn over any documents to the Archivist of the United States or to NARA. The very idea is nonsensical. Donald Trump himself was the Archivist of the United States. All executive power in the Constitution was vested in President Trump. That includes the power to maintain and keep records in the National Archives and Records Administration. The Archivist’s authority flowed directly from Trump. If Trump wished to fire the Archivist and carry out his tasks himself then it would have been entirely legitimate for him to do so. In other words, the Presidential Records Act specifies that the president must turn over his records to…himself. This makes no sense.

It is an absurdity, too, that President Trump’s papers belong, in their entirety, to his successor. Congress has no right to specify how the executive branch is to conduct its own internal business any more than the president can interfere in the legislative process outside of his own limited power of the veto. For instance, the Constitution says, “Each House [of Congress] shall keep a Journal of its Proceedings, and from time to time publish the same, excepting such Parts as may in their Judgment require Secrecy….” The president has no right to tell Congress what it can and cannot keep secret or when it is to publish this journal of its affairs: this is purely legislative branch business.

Joe Biden could claim he had a right to all of President Trump’s papers. But such a claim is unenforceable and absurd on its face. No other entity can settle the dispute between the two men, and the Constitution does not give Congress the power to create penalties by which a sitting president may punish his predecessor for not handing him his entire library. Indeed, this situation is so absurd that it was never contemplated in the nation’s history. This is why, generation after generation of American presidents simply hauled away the totality of their records and papers when they left office without any thought that they would be harassed for doing so.

As president, Donald Trump had every right to know all the business being conducted within the executive branch. He had a right to make and to unmake secrets as he saw fit. In Federalist 70, Publius defends the creation of a unitary executive under the Constitution: “Decision, activity, secrecy, and despatch will generally characterize the proceedings of one man in a much more eminent degree than the proceedings of any greater number….” And this energy will be conducive to good government. “Secrecy” is mentioned explicitly as a quality of the presidency. The president, in the Founders’ view, had a right to keep secrets. A right to make secrets is a right to unmake them.

The entire logic of classification of documents flows from executive orders made by presidents. The president, in this system, is an “original classification authority.” He decides what is and is not secret. As Larry Pfeiffer, a former intelligence official who served as senior director of the White House Situation Room and chief of staff to the director of the Central Intelligence Agency, explains, the president has “the ultimate classification and declassification authority.” Jeffrey Fields, a Professor at the University of California, argues that “the most prominent example” of this ultimate classification authority “is when President Obama declassified the number of nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal. He decided it was something the American people should know, and he wanted to show that the numbers were coming down as part of his non-proliferation initiatives.”

These men are exactly correct. Their logic is entirely consistent with the Founders’ understanding of the role of the president in our constitutional order.

Donald Trump had the power to take whatever documents he wished wherever he wished and show them to whoever he wished as president. Any documents in his possession after the presidency are presumptively declassified for his purposes. Jack Smith alleges that Trump sometimes told people that the documents he possessed were still classified even in his possession and that he was not allowed to publish them. This is irrelevant.

It is impossible for Donald Trump to have unauthorized access to his own documents even when he is out of office. If he has them then that means he has a right to have them. No other reading of the Constitution makes any sense whatsoever. If Joe Biden can “reclassify” those documents in President Trump’s possession, then Biden could just as easily classify any document whatsoever in anyone’s possession as a matter of “state security.”

The president, when out of office, is a private citizen like anyone else. He has the same right to his papers as any other citizen. The Fourth Amendment protects him from unreasonable search and seizure in his “papers and effects” (emphasis mine) as much as it protects anyone else. If Joe Biden could lawfully classify President Trump’s papers and then demand they be turned over to himself, he could make such a demand of any other American, and the right to protection from unreasonable search and seizure would evaporate into thin air. Again, this reading is ridiculous and untenable.

By the logic spelled out here, Section 2202 of the Presidential Records Act is a nullity. There is no “United States” which can own the president’s documents. The federal government created by the Constitution has precisely three branches, made up of Congress, the president, and the Supreme Court. Only one of those coequal entities must own the president’s documents. That entity is, obviously, the president himself.

As we have shown in the above arguments, under the Constitution of the United States, the President of the United States outranks the archivists at the National Archives and Records Administration; Congress has no right to infringe on the prerogatives and privileges inherent to the executive branch; and the idea that the former President of the United States can be prosecuted for possessing documents relating to the workings of the executive branch is spurious on its face.

Jack Smith’s prosecution is rooted in an utterly nonsensical reading of the law, the facts, and constitutional history that, if implemented, would mean the complete undoing of even the pretense of government by consent as it relates to the executive branch. As President Trump has already stated repeatedly, this case is a witch hunt and a banana republic tier political prosecution designed by the ruling political faction to destroy its most prominent opponent.

Americans must firmly denounce and castigate this prosecution, its logic, and the wicked political actors who perpetrate it.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Undoing a corrupt eminent domain case doesn’t justify society-wide wealth redistribution.

Trump’s call to end birthright citizenship is a necessary corrective.

Too often, experts who are working to "save American democracy" are doing anything but.

Critical race theory was never designed to reveal truth—it was designed to achieve power.

Jack Smith’s indictments of Donald Trump are unconstitutional because he was already tried in the Senate.