Ruthless outsourcing will be the death of the American Dream.

Whose Country Is It?

Trump’s call to end birthright citizenship is a necessary corrective.

Former president and current presidential candidate Donald Trump pledged to end birthright citizenship in a recent campaign announcement, promising to sign an executive order on his first day in office to prevent “the future children of illegal aliens” from receiving automatic citizenship. The proposal promises to clarify at least a century of constitutional ambiguity on the subject of American citizenship and its automatic bestowal upon anyone born on the soil of the nation. Immigration has emerged as the most important domestic issue in the 2024 election cycle, with estimates of upwards of ten million illegal aliens flooding the country under the Biden regime. The magnitude of the ongoing crisis far surpasses the number of illegal border crossings in the lead up to the 2016 presidential election, when then-candidate Trump first proposed the idea in response to a crisis whose scale was itself unprecedented for the time. Nearly a decade later, the problem has only worsened. The need for dramatic action—even more than in Trump’s first term—is palpable.

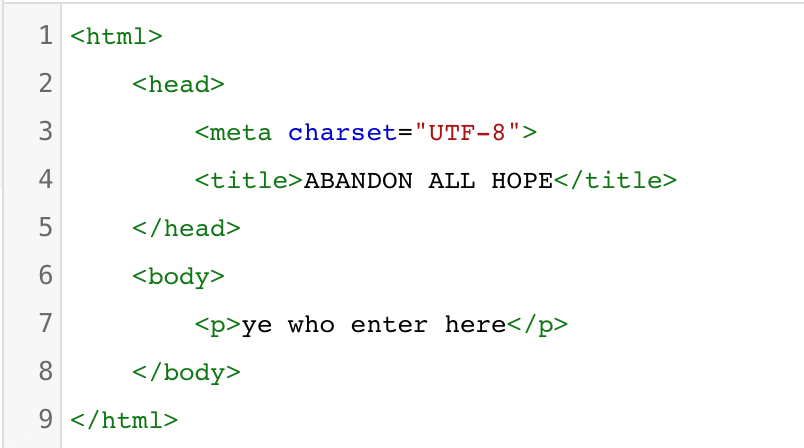

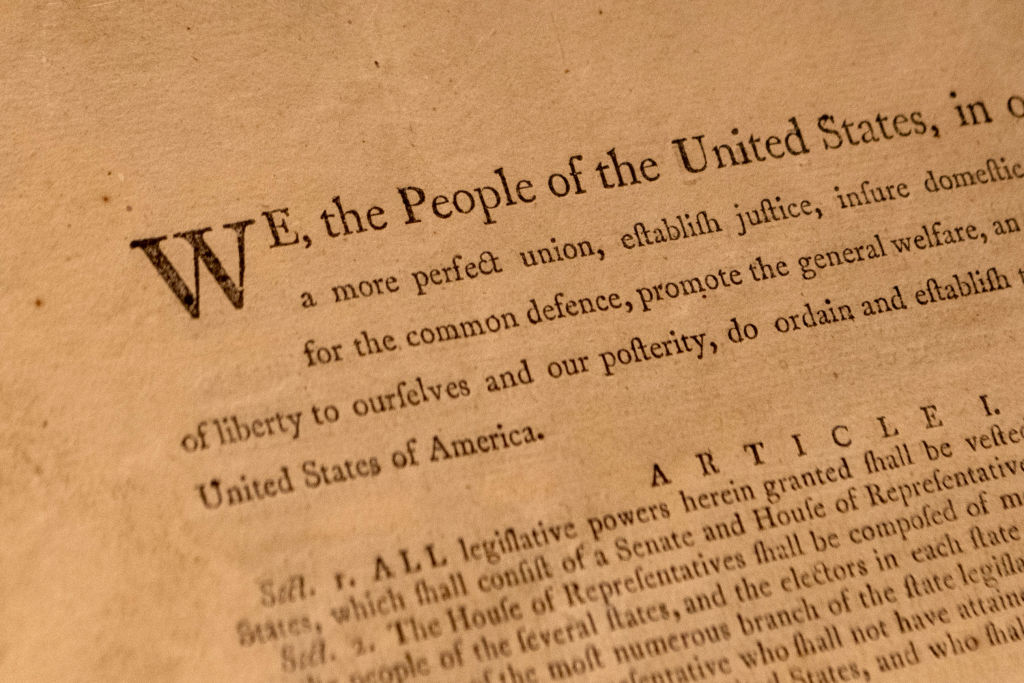

The idea that the Fourteenth Amendment does not license birthright citizenship based on its proper, constitutional interpretation has found support from both legal scholars and political historians. The text of the amendment itself reads, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.” Of controversy is whether the phrase “all persons born or naturalized in the United States” should be read in conjunction with—“and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” As scholars John Eastman and Michael Anton, as well as others, have persuasively argued, the plain meaning of the text itself requires that both elements of that constructive phrase be satisfied in order to qualify for the fruits of citizenship. In other words, a person must not only be born “in the United States”—i.e., the geographical region over which the laws of the United States apply—but also be “subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” To fully qualify for citizenship, a person born within the United States must owe no allegiance to any other sovereign—he or she must, in other words, exclusively qualify under the laws of the United States alone.

Under the common law, the concept of ligealty provided a necessary condition for citizenship. This was elaborated at great length by Chancellor James Kent, who has been hailed as the American Blackstone. Indeed, Kent’s Commentaries on American Law were cited in the controversial Supreme Court decision United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898), a patently erroneous decision that has nonetheless deeply influenced the Fourteenth Amendment’s construction to require so-called “birthright citizenship.” In Wong, the Supreme Court established that persons born of permanent domiciles under the laws of the United States would be automatically granted citizenship. The outcome is quite odd, and not only for its constitutional construction. But also because the Court decided to cite—and then ignore—Kent’s own words, “to create allegiance by birth, the party must be born not only within the territory, but within the ligeance of the government” (emphasis added). Thus, the two-part requirement of the amendment’s construction that Eastman delineated well over a century later has a longstanding precedent in American legal scholarship, and enjoys the blessing of some of the most foremost authorities in the history of American law, no less.

Even if, irrespective of Chancellor Kent’s learned interpretation, Wong’s outcome stood, there are several other major complications with the preferred construction. First, Wong itself only licenses citizenship to persons born of permanent residents or domiciles—in other words, those who have been sufficiently vetted and have gone through the arduous logistical process already to meet those requirements. Second, the policy considerations have changed significantly since the late nineteenth century. America today is overcrowded and increasingly unable to meet the basic needs of its native population—food, water, public transportation, basic infrastructure—as is. Thus, the prerogative to end birthright citizenship on the basis of more pragmatic concerns obtains currency.

The undesirable and unsustainable practical consequences of birthright citizenship flow from an absurd principle. The prevailing doctrine declares that foreigners have a right to become American just by having a pulse, that citizenship is an entitlement rather than a privilege of those already belonging to the political community. But to argue this is to negate the right of the people to political independence. What could be more perverse than to reward those who trespass America’s borders by welcoming their descendants with the privilege of citizenship, and all the entitlements attached to it? A sane country does not confer citizenship on just anyone who sets one dry foot on its territory.

To continue the present course would be to allow an egregious constitutional error to defraud the American people of their patrimony. In The Political Theory of the American Founding, Thomas G. West notes that the Founders upheld the right to exclude from the fledgling nation those unfit to receive its blessings. An immigration policy that made citizenship available to non-Europeans, West writes, “would have been rejected by all.” The very first naturalization law made citizenship available only to people of European descent with “good character.” In his Notes on the State of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson warned that immigrants from the kingdoms of Europe “will bring with them the principles of the governments they leave, imbibed in their early youth” and “warp and bias” the law to reflect their alien principles.

Is this not the woeful state of America today? Those attached to the American way of life are facing political obsolescence as the citizenry grows ever more foreign and unpatriotic. There are large masses of unqualified people participating in the political process, bereft of any knowledge of American history or principles, supposing they aren’t actively hostile to them. Their ranks swell with each new generation of anchor babies, whose numbers are easily in the hundreds of thousands per annum. Trump’s proposal is a direct challenge to the regnant anti-American ethos, which serves to dilute the meaning of citizenship and alienates the people from their government, which increasingly operates like a Third-World banana republic.

Last, there is an increasing awareness within at least conservative legal circles to not overly dogmatize the Fourteenth Amendment. Considering that the amendment has been used for well over a century to justify a smorgasbord of horribles—from subversive policy outcomes, ranging from birthright citizenship, to abortion, to same-sex marriage, to removing prayer in schools, to transgenderism—to equally subversive jurisprudential tests—tiers of scrutiny, substantive due process, etc.—conservatives should heed the advice of Justices Thomas and Alito, especially in recent decisions, and not place the Fourteenth Amendment on a pedestal in light of its destructive weaponization by the Left over decades, whose effect has been to gut our Constitution root and branch.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Securing the means of reproduction.

Climate apocalypse porn is a lever to impose a radical economic agenda.

American campuses have become the last place to find open debate about controversial matters.

A skills-based immigration system is a possible answer to American demographic decline.

Identity politics can’t rule the digital swarm. What can?