Alabama’s great public universities are folding to the diversity agenda.

No Credit

Our system of university accreditation empowers unaccountable authority.

When the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) Board of Trustees passed a unanimous resolution calling on campus leaders to “accelerate” the “development of a School of Civic Life and Leadership” in late January, Belle Wheelan, president of one of the largest higher education accreditors in the country, immediately moved to kill the initiative.

Though the actions of accreditors go largely unnoticed by the public, their sway over higher education is immense, because they are the de facto gatekeepers to federal higher education funding. This is not the first time the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC or SACS) has used its influence to undermine a governing board or a state’s vision for its public campuses. But SACS’s opposition to a much-needed initiative to improve intellectual diversity at UNC is surely among the most egregious.

A detail that would later emerge—that President Wheelan threatened the accreditation of a premier state university without even reading the board resolution at issue—indicates that her goal was to bully the university into abandoning its civics initiative. The lesson to draw from the UNC story is that higher education accreditation is in desperate need of comprehensive reform. Absent change, every innovative university president is likely to run into a buzzsaw of capricious political meddling and entrenched resistance to higher education reform at the hands of unaccountable and highly ideological accreditation bureaucrats.

Ostensibly, accreditors are membership organizations tasked with ensuring quality. They derive their tremendous power from the fact that U.S. students can only access federal student loans (and Pell grants) if they attend colleges and universities that have an accreditor’s formal stamp of approval. This allows accreditation agencies to supervise and influence campus operations, the composition of the faculty, and even a school’s curriculum by requiring schools to submit to an intrusive and costly periodic accreditation review. SACS’s opposition to a new academic center at UNC illustrates how accreditors stifle innovation and preserve a dysfunctional status quo.

Nor are they shy about admitting it. In a presentation to North Carolina’s Commission on the Governance of Public Universities (a body established by the governor with no formal governance authority), Wheelan promised her audience that a letter from SACS was in the mail “because the board, without input from the administration or faculty, had decided they were going to put in this new curriculum offering…. [T]hat’s kind of not the way we do business.” “We’re gonna see the committee,” she went on, adding an ultimatum, “and…either get them to change it, or the institution will be on warning with [SACS], I’m sure.”

Why is SACS threatening the financial viability of a major state university? The issue appears to be the board’s vision for an interdisciplinary academic center designed to revitalize liberal (in the traditional, non-political sense of the word) education by bringing intellectual diversity to the campus. As Board Chair David Boliek and Vice Chair John Preyer explained to The Wall Street Journal, their goal is to end “political constraints on what can be taught in university classes.”

By establishing a new academic center, Board members are responding to documented problems on the state’s flagship campus. A recent study of faculty voter registrations at UNC found that 16 professors are registered Democrats for every one registered Republican. Students have noticed the severe partisan imbalance. When the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression surveyed UNC students in 2022, 72% said the “average faculty” member is on the political Left (compared to 4% who said “slightly” or “somewhat” conservative). The result is a campus on which 60% of students say they are “very” (30%) or “somewhat” (30%) uncomfortable “publicly disagreeing with a professor about a controversial topic.” A separate study focused on North Carolina campuses found that conservative students on the Chapel Hill campus are much more likely to exercise self-censorship (54%) than their liberal (8%) and politically moderate (21%) peers.

A board that ignored serious problems with the campus intellectual environment, documented by careful empirical research, would be derelict, which takes us to the faculty’s response. Instead of embracing a proposal to enrich campus life by adding new faculty positions in the humanities and social sciences—a rarity in academia today—UNC faculty leaders immediately condemned the move. The UNC faculty chairperson explained to a Daily Tar Heel reporter that “a key principle of shared governance is that the faculty is in charge of the curriculum.”

One wonders if the chairperson forgot to read the resolution too. In fact, the board did not create a new curriculum, interfere with classroom teaching, or demand changes to an existing course or academic program. It simply prioritized the development of a new school focused on cultivating public leadership and civic-mindedness. Much work will remain for the faculty and academic administration.

This is not the first time President Wheelan has used the prospect of negative accreditor action to interfere with a university board’s legitimate governance prerogatives or a governor’s attempt to ensure institutional accountability to taxpayers. Higher education leaders in Florida, South Carolina, Kentucky, and Virginia have all had recent run-ins. All the while, institutions with sky-high cohort default rates and dismal graduation rates remain in good standing—failing to prepare students for family-sustaining careers while they rack up mountains of debt. A recent analysis by Andrew Gillen found that SACSCOC has the worst record of all the regional accreditors when it comes to ensuring students are not leaving campus with excessive student loans.

Higher education quality will improve when accreditors are held accountable. Recent legislation in Florida requiring state institutions to seek reaccreditation under a new accreditor in their next affirmation cycle (which will have the practical effect of forcing them to leave SACSCOC) is an important first step. State leaders around the country should ask themselves whether their current accreditor allows state universities to innovate and advance the public interest. For those who say “no,” changing accreditors is now possible, thanks to regulatory changes made during the Trump Administration.

It is also time for the Department of Education to ask whether SACSCOC has abused its role as gatekeeper to the public’s tremendous investment in higher education. When SACS next applies for federal recognition, a status it must renew every five years, the Department of Education should seek assurances that the organization will stop abusing its authority. If the Department does not ask hard questions, Congress can. Ensuring that accreditors are upright stewards of the $135 billion in federal grants and aid the United States invests in higher education annually justifies regular and meaningful oversight.

The American Mind presents a range of perspectives. Views are writers’ own and do not necessarily represent those of The Claremont Institute.

The American Mind is a publication of the Claremont Institute, a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to restoring the principles of the American Founding to their rightful, preeminent authority in our national life. Interested in supporting our work? Gifts to the Claremont Institute are tax-deductible.

Classical education is rising up to take its place.

American Education and the Cult of Victimhood

The University of Pennsylvania Law School is gunning to expel a heterodox professor.

When STEM goes woke, the university system is through.

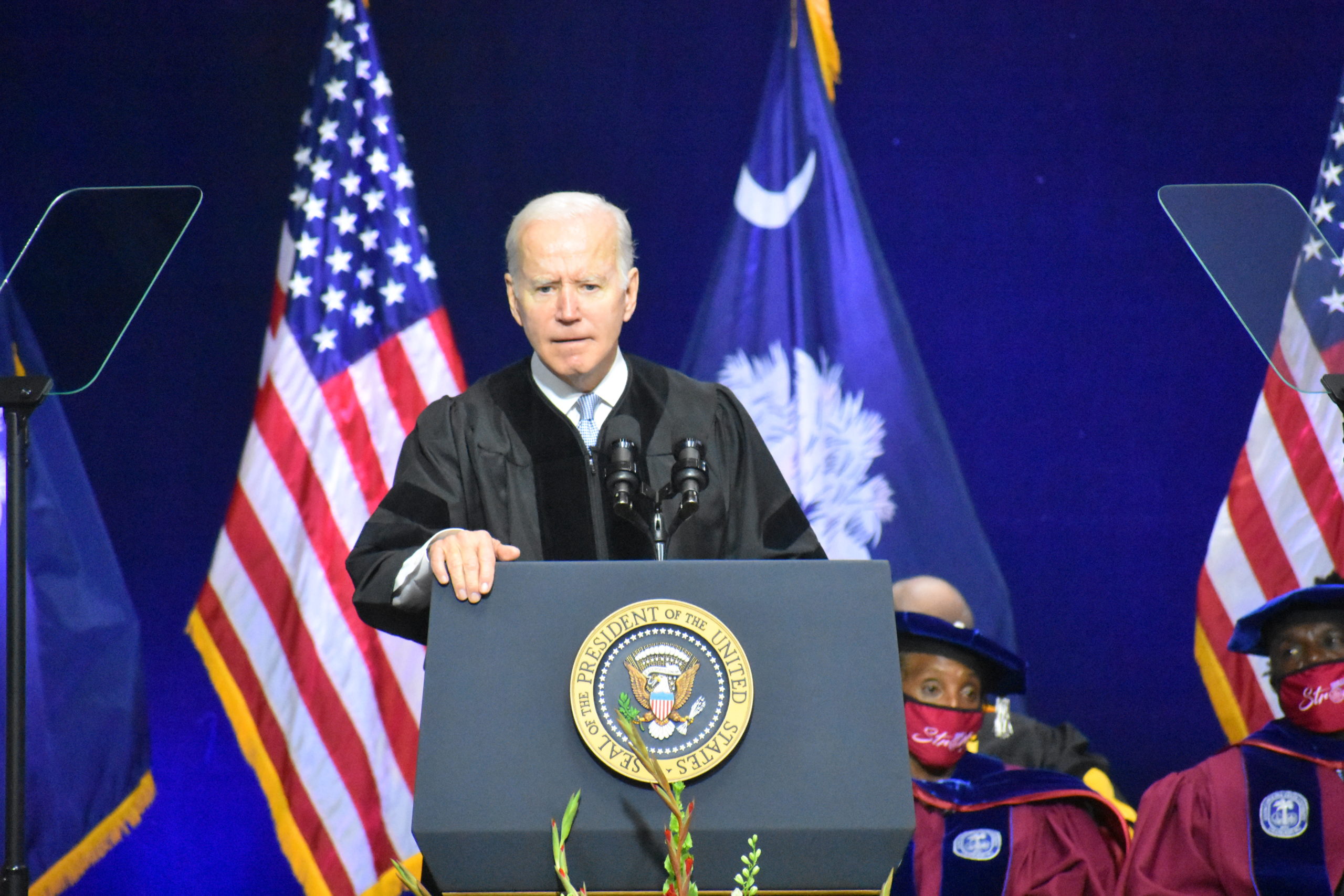

The Biden administration seeks to impose a radical ideology on campuses.